“`html

Arts & Culture

Creating a niche in outer space for the humanities

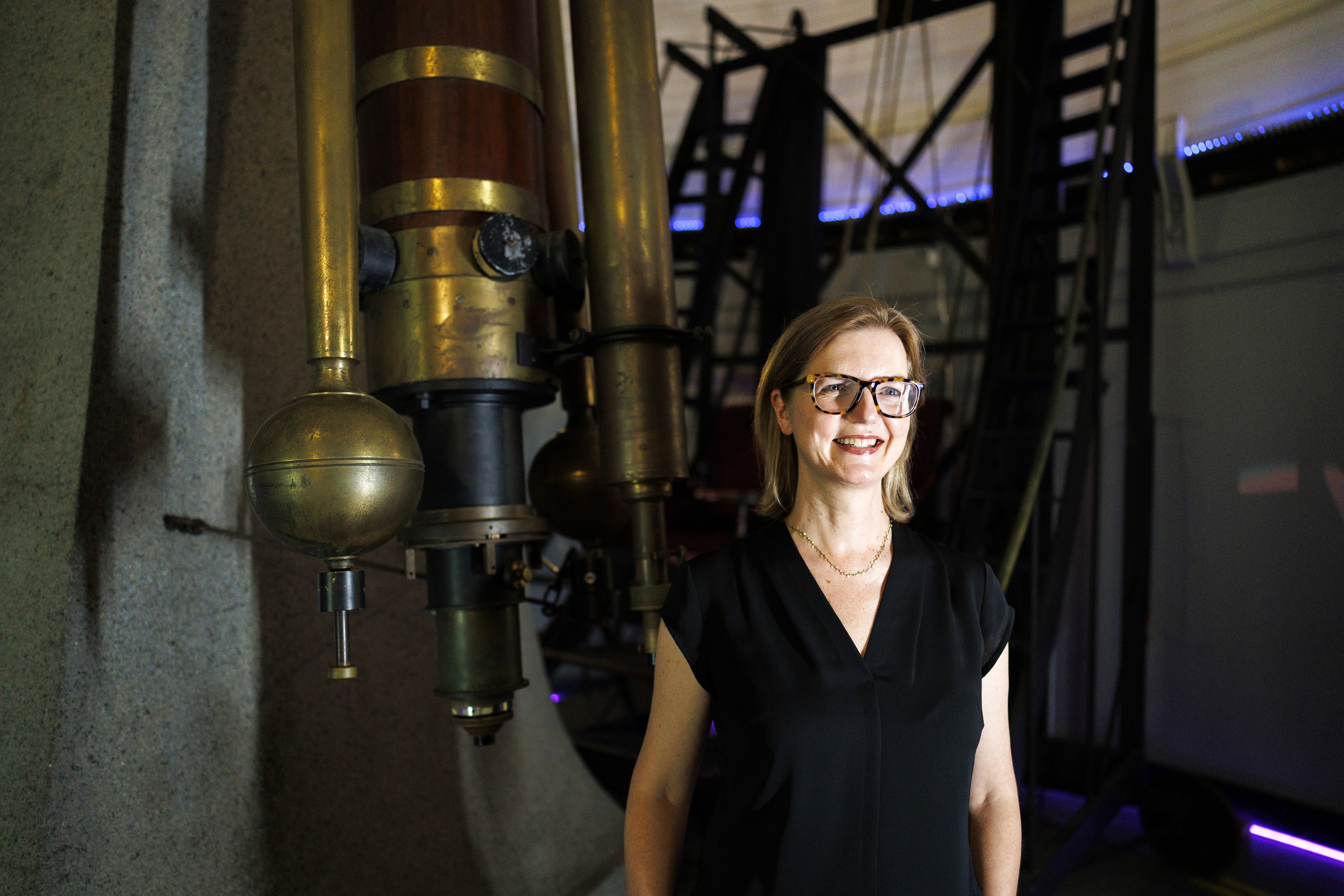

Jennifer L. Roberts.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Cosmos ‘is as peculiar and remarkable as any significant piece of art,’ contends Jennifer Roberts, asserting that navigating it necessitates ‘a new type of ethics’

Jennifer Roberts is an art historian whose investigations revolve around an unexpected theme: outer space. Enchanted by visuals generated to comprehend the unknown, she fosters collaborations between scientists and humanists—efforts she deems increasingly crucial as we embark on an era of commercial space exploration.

“Astronomers and art historians ought to collaborate whenever possible,” stated Roberts, the Drew Gilpin Faust Professor of the Humanities. “We both recognize that images are not merely decorations; they are instrumental for comprehension and interpretation, wielding significant influence over how humanity will process the insights science reveals about the cosmos.”

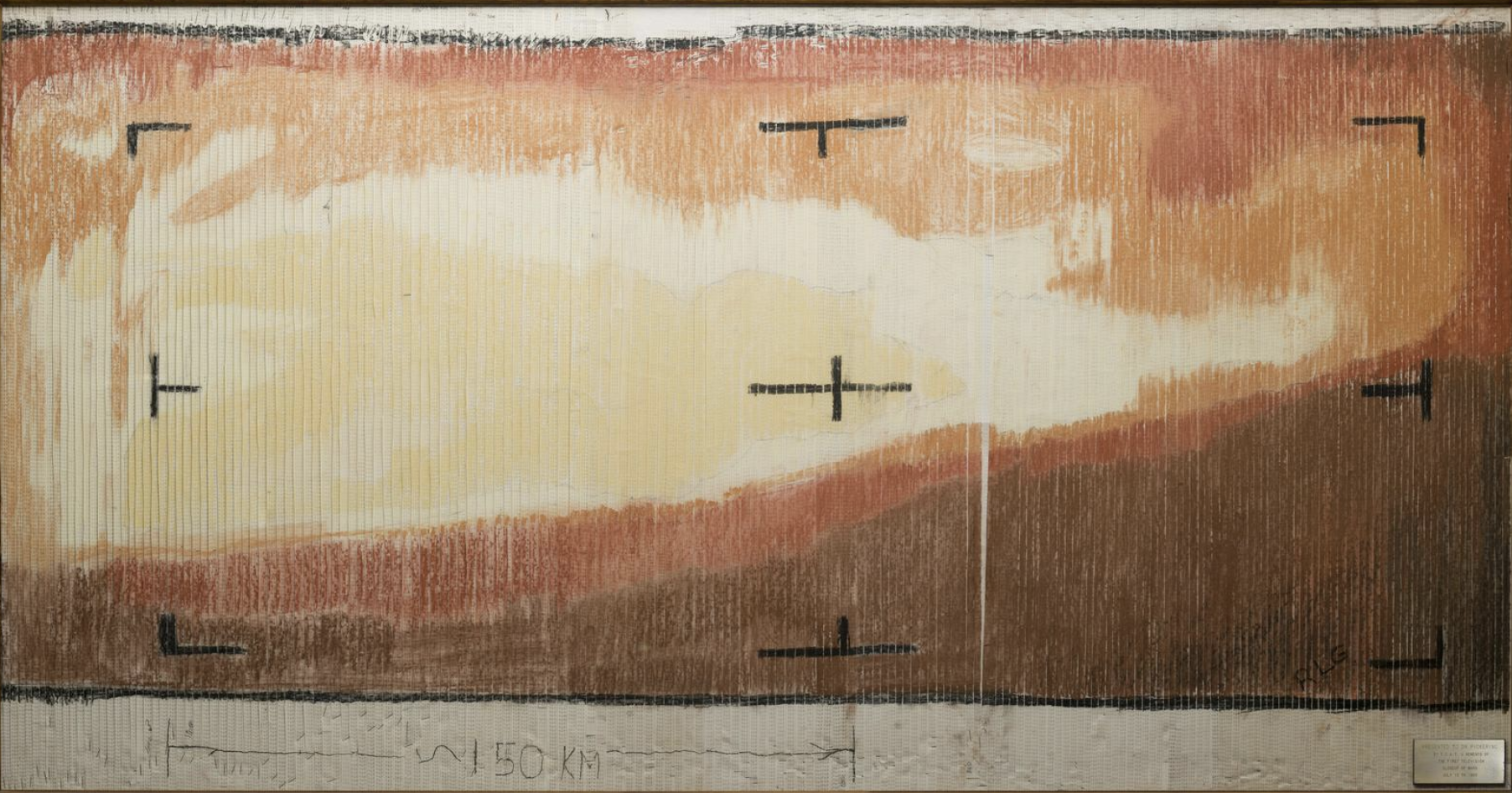

Roberts plans to release a study later this year examining the first image sent from Mars, intriguingly rendered in pastel on paper. In 1965, the 21 images captured by the Mariner 4 probe during its flyby of Mars were transmitted too slowly for scientists at the Pasadena Jet Propulsion Laboratory: Each required eight hours for processing. Eager for the initial view of the then-mysterious planet, they procured a box of Rembrandt soft pastels from a nearby art supply store, affixed the incoming numerical data to a wall, and colored by number each pixel using a color-code system where brown symbolized the darkest parts of the image and yellow the brightest.

“This narrative fascinates me because it highlights one of the numerous ways scientists depend on visualization,” Roberts noted. “They needed to produce an image to interpret the data. It’s noteworthy that they utilized the fugitive, gritty medium of pastel for this—artists have historically employed pastel as a visual tool for perceiving concealed or fleeting realities.”

A real-time data converter machine transformed Mariner 4 digital image data into numbers printed on strips of paper. The team manually colored the strips with pastels, rendering this both a piece of art and the first digital image from beyond Earth.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Roberts, who credits her fascination with science and the humanities to viewing Carl Sagan’s “Cosmos: A Personal Voyage” on PBS as a child, is also in the process of writing a book about the Voyager Golden Record, which she describes as the “most distant work of art ever made.” “The Heartbeat at the Edge of the Solar System: Science, Emotion, and the Golden Record,” a partnership with artist and writer Dario Robleto, will be published by Scribner in 2026.

Her additional research interests include the astronomical photographic glass plate collection at the Harvard College Observatory, as well as contemporary artists like Anna Von Mertens and Clarissa Tossin, who are integrating outer space data into their creations.

Visual representations of space influence our perceptions of it, Roberts elaborated, particularly the visuals frequently disseminated by NASA, such as those captured by the Webb and Hubble telescopes, which aren’t raw images but rather meticulously crafted visuals derived from data captured outside our visible range. The images are colored, cropped, rotated, and edited to assist viewers in making sense of something fundamentally alien, she stated. These aesthetic decisions are essential for visibility, yet they can alter our understanding of outer space, often rendering it seem closer and more digestible than it truly is.

Roberts referenced research by Stanford scholar Elizabeth Kessler, who discovered that Hubble visualization scientists often styled cosmic imagery to mirror 19th-century American West paintings—indirectly framing the cosmos as an enticing, navigable frontier.

Roberts expresses admiration for the skill and creativity underlying these visuals. “However, there are countless alternative ways to portray the same data, and it’s crucial for people to recognize that,” she asserted. “The well-known ‘Cosmic Cliffs’ image, in which a nebula appears as a rocky formation, could have been flipped upside down, retaining scientific validity. Various other colors could have been employed. It could have appeared much, much more bizarre.”

She harbors concerns regarding commercial space endeavors that present outer space as “up for grabs.” Its narrative, she suggests, closely resembles Earth’s most damaging colonial tendencies.

“We are on the verge of stepping off our planet and I worry we may replicate the same errors we’ve previously made,” Roberts remarked. “We are depicting space as a ‘frontier’ meant to be colonized or occupied. Yet, we ought to heed what science imparts: Space is as peculiar and remarkable as any extraordinary piece of art. It does not uphold the status quo.”

This perspective is one reason Roberts believes humanists should play a more prominent role in discussions regarding outer space. She has observed a trend among some humanities scholars dismissing space as escapist or bizarre, a diversion from Earth’s pressing issues, yet she contests this view.

“We’ve somewhat surrendered the cosmos to the technology sector, to scientists, to commercial endeavors,” Roberts remarked. “It seems to be a domain where we can’t apply our expertise. But while we’ve been distracted, we’ve approached a new space era that is now upon us. Our expansion into space will demand an entirely new type of ethics and philosophy, which we can’t access without the arts and humanities collaborating closely with scientists.”

“Our expansion into space will demand an entirely new type of ethics and a totally new philosophy and we aren’t going to be able to access that if we don’t have the arts and humanities involved in close collaboration with scientists.”

Jennifer L. Roberts.

To actualize this notion, Roberts has initiated a course titled “Art and Science of the Moon” in the Department of History of Art and Architecture. The innovative seminar examines the global history of artistic engagement with the moon, encompassing the reactions of photographers and conceptual artists to the Apollo program in the 1960s and ’70s. She aims to offer a similar course focused on Mars.

Additionally, she is launching a seminar at the Mahindra Humanities Center this fall titled “Celestial Spheres,” meant to unite scientists and humanists to discuss phenomena occurring beyond our planet.

Roberts envisions outer space as akin to an ocean in which we are immersed rather than a void filled with tangible targets.

“What would it imply if we didn’t consider it a frontier to conquer?” Roberts pondered. “What if we perceived it as an ecosystem, something to which we are already connected?”

“`