“`html

Labor & Economy

Is Trump able to dismiss the Fed chief?

U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell during a press conference after a Federal Open Market Committee meeting in March.

Photo by Sha Hanting/China News Service/VCG via AP

Law professor and former Fed Board member states it’s feasible, but market responses may warrant caution

President Trump has maintained a challenging relationship with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

Fears regarding Trump’s international tariff strategies unsettled markets earlier this month. Powell, who was first appointed by Trump in 2017, remarked that the president’s strategies might result in elevated inflation and diminished growth.

Trump has accused the Fed chair of inadequately stimulating the economy by not taking a more assertive stance on interest rate reductions. (The two have also clashed over rates during Trump’s initial term.) He also suggested he was considering firing Powell prior to the expiration of his four-year term next year, which further disturbed markets.

Numerous analysts opined that such an act could severely compromise the Fed’s long-standing autonomy and is, per Powell, “not authorized by law.” Trump subsequently stated he had no intention of dismissing Powell.

In this modified dialogue, Daniel Tarullo, Nomura Professor of International Financial Regulatory Practice at Harvard Law School, talks about the possible repercussions if the president follows through on his threats to remove Powell. Tarullo was a member of the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which regulates interest rates, from 2009 to 2017.

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 permits governors to be dismissed for cause, yet it does not address the FOMC chair. Do you believe a president, as the leader of the executive branch, possesses the power to remove Powell?

There are two distinct matters. One concerns statutory interpretation — whether the amendment to the Federal Reserve Act introduced in the 1970s, mandating Senate confirmation for the chair for a four-year term, includes the “for cause” protection that the original Federal Reserve Act provided to all Board of Governors members.

The alternative interpretation would argue that the four-year term for the chair as chair lacks the “for cause” guarantee.

The second matter revolves around whether — regardless of the Federal Reserve Act’s wording — the Supreme Court deems that the Constitution grants the president the authority to remove anyone at an independent agency who performs what the court recognizes as “executive” duties. These two matters are interconnected, but initially, they are indeed separate.

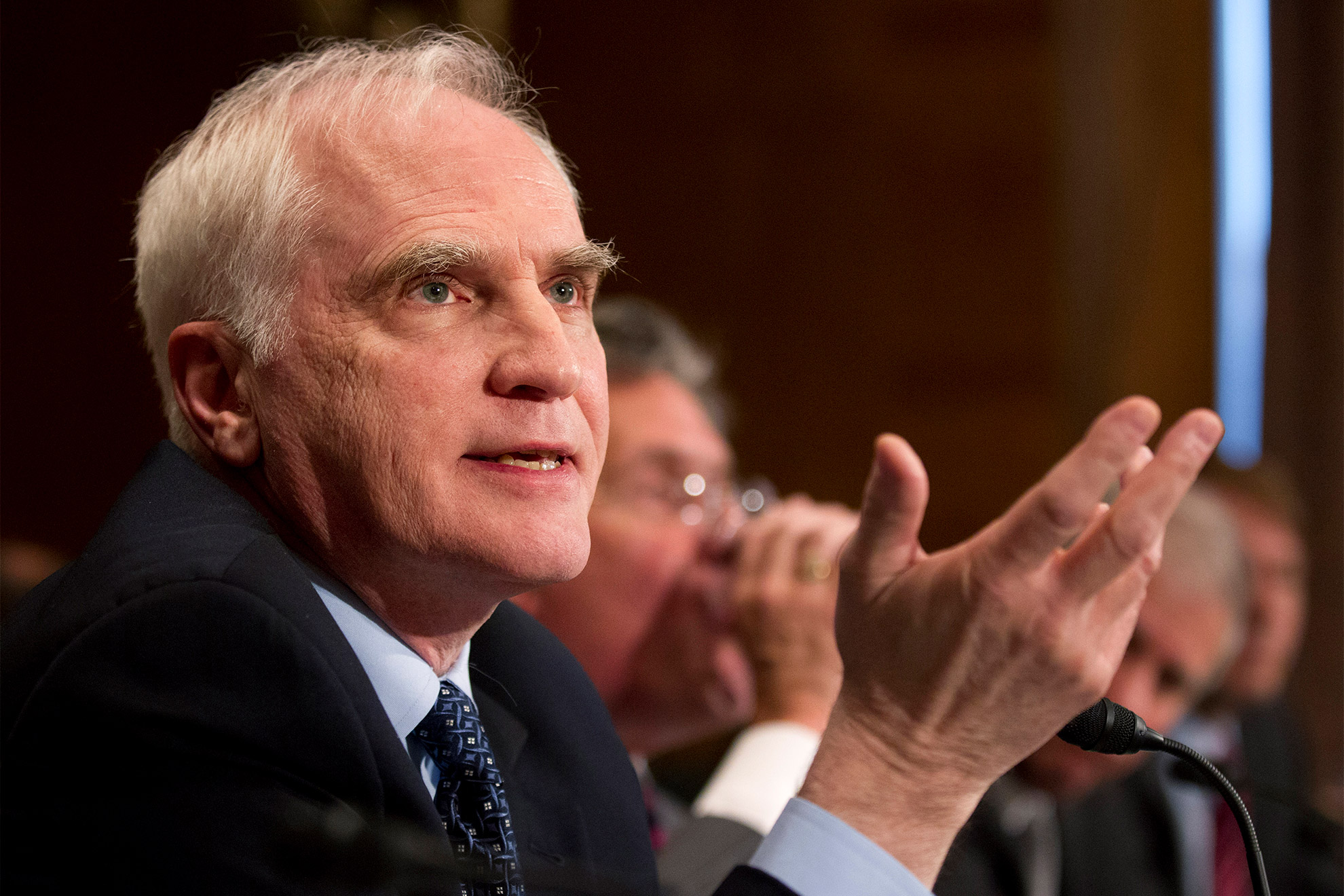

Daniel Tarullo.

Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP file photo

Is the Supreme Court likely to endorse such an action given recent rulings on the extent of executive authority?

I believe most analysts anticipate some further weakening of the iconic 1935 ruling Humphrey’s Executor, which for 85 years was understood as affirming “for cause” safeguards for key figures at independent agencies.

Whether the court will gradually erode Humphrey’s or eliminate it in one fell swoop remains uncertain.

The question, however, would be if the Fed (and perhaps other agencies) would be regarded differently. There have been indications from three conservative justices — Samuel Alito, John Roberts, and Brett Kavanaugh — that they may view the Federal Reserve in a different light compared to other agencies.

They might still uphold a broad interpretation of the president’s authority, yet favor an exception for the Fed?

Indeed. None of the three justices has provided more than a hint at a possible distinction, so we lack a clear understanding of their justification for such differentiation.

A possible argument lies in the legacy of the Federal Reserve stemming from the First and Second Banks of the United States. There could be an assertion that from the inception of the first Congress, convened immediately after the Constitution’s ratification, there was recognition that Congress could establish an independent central bank.

The First Bank of the United States was not a central bank as we conceptualize one today, yet in the late 18th century, it was quite akin to what was then envisioned as a central bank, characterized by the Bank of England. Thus, this argument is available, though it is not overwhelmingly strong. Additionally, I believe that the court’s recent decisions concerning the “for cause” removal protection have not been convincingly compelling, allowing for potential selective interpretation by the court.

Is there a solid legal argument for dismissing Powell prior to his term’s conclusion?

We can revisit the 85 years of prevailing doctrine that established “for cause” protections for independent agencies.

However, the Supreme Court cast significant doubt on this principle in Seila Law, the 2020 case which determined that Congress’ provision of “for cause” removal protection for the head of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau was…

“““html

unconstitutional.

Thus, it is the judiciary that has altered the 85-year-old interpretation, leaving open the inquiry of how extensively it will eventually revise Humphrey’s Executor.

If the president were to attempt to dismiss the chair, the market response would be profoundly impactful — well before any court could weigh in on the matter. The expected market outcome serves as a deterrent against attempting to displace the chair, regardless of how dissatisfied the administration might be with his policies.

Considering Powell’s term as chair now has merely a year remaining, that might be another rationale for simply waiting until the president can appoint his own candidate as a successor. Therefore, at some level, the market functions as much as a safeguard for the Board of Governors as the law may finally prove to be.

Why is Wall Street uneasy about the possibility of Powell’s removal?

Current administrations typically favor a more lenient monetary policy to foster short-term economic expansion. The reason for maintaining some autonomy for a central bank is that central bankers can assess the potential repercussions on inflation over the medium term and strive to keep inflation in line with what is currently a 2 percent target for the Fed. It’s a straightforward rationale, yet a compelling one.

Markets are apprehensive that if a president decides to dismiss the chair or other Board members, it would be with the goal of adopting a more lenient monetary policy. At that moment, the market’s confidence in the central bank would be significantly eroded, consequently weakening its credibility as a combatant against inflation. Long-term interest rates would then likely escalate, perhaps quite significantly.

There exists the potential for an unusual scenario where the Fed, in tune with the administration’s push for short-term growth, reduces short-term rates, yet markets, perceiving this as inflationary, would essentially demand a higher premium for holding longer-term Treasuries and other extended debt. This is why I believe any efforts by any administration to remove the chair or board members would ultimately be counterproductive.

Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent has understandably concentrated on the 10-year Treasury yield, as that yield is crucial for investment choices across the economy. One could presume the administration aims to avoid elevating that rate due to market uncertainties.

What extent of influence does the chair really wield over internal policy discussions?

There remains a considerable public misunderstanding regarding just how influential the chair is within the board and the FOMC.

During Alan Greenspan’s tenure as chair, his inclinations and decisions seemingly predominantly steered FOMC outcomes. By the time I joined the Board of Governors in early 2009, that was certainly not the situation. I believe Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, and now Jay Powell have all had to engage in considerable internal dialogue and efforts to build a consensus surrounding monetary policy.

It is undeniable that the chair is by far the most significant individual on the FOMC. However, it is not accurate that the chair can simply command what the policy will be and expect the rest of the FOMC to comply.

If Powell were succeeded by someone with a particular background, would that alleviate market concerns?

I think if there were an attempt to remove him, the background of the successor wouldn’t be particularly significant, as I believe markets would interpret the act of removal as an intention to pursue a considerably more accommodating monetary policy.

If Jay Powell is permitted to complete his four-year tenure, then certainly the identity of the person the president chooses to succeed him will be of considerable interest to the markets.

“`