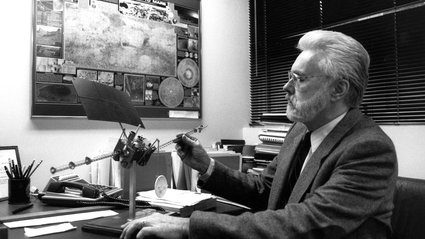

Arden L. Albee, emeritus professor of geology and planetary science, as well as the principal scientist at JPL, departed this life on March 19, 2025, at the age of 96. Albee engaged in petrological studies across the United States and Greenland, and ultimately with samples from the Moon and Mars.

Albee was born and raised in Michigan, the offspring of two educators. He began his rock collection at an early age, a pastime he nurtured through family excursions across the Dakotas and Montana, Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, and into Canada.

During his undergraduate and graduate studies at Harvard, he commenced with no definitive objective regarding the direction of his education. “I contemplated becoming a lawyer,” Albee reflected in a 2017 oral history interview. “I can’t explain why; I wasn’t acquainted with any lawyers.” Ultimately, Albee chose to major in geology. “I perceived that others had no intention of extracting a career from their four years; they were heading to business, law, or medical schools, and I couldn’t envision how I would afford to embark on any of that. Yes, I was fond of geology—the introductory course was exceptionally good. However, I believe my decision was influenced by the understanding that upon graduation in four years, I would be able to secure employment,” Albee articulated.

Nonetheless, after obtaining his undergraduate degree in 1950, Albee remained at Harvard to secure a master’s degree in 1951. He subsequently conducted fieldwork for the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in Vermont. As he reminisced in his oral history, after three or four years, Albee came across a piece in the Sunday New York Times regarding a National Science Foundation (NSF) scholarship. He applied, succeeded, and returned to Harvard to pursue a PhD in geology, which he attained in 1957.

Albee’s dissertation focused on his USGS endeavors in Vermont, but prior to the completion of his doctoral studies, he was already reengaged with the USGS in Colorado and subsequently in Maine, exploring for uranium, zinc, and other elements with industrial or military relevance.

In 1959, he was invited to Caltech as a visiting assistant professor, covering for a fellow geologist on sabbatical. Eventually, he was asked to remain, this time as an associate professor of geology. In 1966, he advanced to full professor and, in 1999, became a professor of geology and planetary science, acknowledging his geological research beyond Earth.

Albee’s research pursuits continued to emphasize petrology. In his early career, he meticulously identified minerals in rocks by slicing thin sections and scrutinizing them under the microscope, as was customary at the time. Later, he partnered with colleagues at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), managed by Caltech, to acquire an electron microprobe, an instrument that utilizes an electron beam and X-ray diffractometers to identify minerals in rocks. The initial electron microprobes could examine only three elements each day, with data recorded on computer punch-paper tapes and, eventually, on punch cards. Recognizing minerals in rocks—which he sourced from locations such as Death Valley and Greenland—was a labor-intensive task until the introduction of a new electron microprobe in 1971 that allowed geologists like Albee to analyze mineral samples in mere minutes, right in the field.

This experience with advancing petrological technology led NASA to recruit Albee to analyze lunar samples, starting with those collected during the Apollo 11 mission in 1969. He identified the mineral composition and structural characteristics of these Moon rocks, assessing them for traces of ancient meteoric particles. Among Albee’s findings was the revelation that the Moon rocks were older than any previously identified specimens on Earth. As the Apollo initiatives concluded and the Viking Mars missions commenced in the mid-1970s, Albee developed remote-sensing instrumentation that could evaluate Martian rocks from the perspective of an orbiting spacecraft.

In 1979, Albee transitioned to JPL as chief scientist, a role he occupied until 1984. In his oral history interview, he noted that JPL possessed a “totally different atmosphere” compared to Caltech. “The first thing I discovered was that if I made a passing comment, someone would take action to address it.”

At JPL, Albee gained administrative experience; he participated in numerous committees and authored JPL’s annual report. He also contributed to overseeing a digital transformation in spacecraft as computers became fundamental components of each onboard instrument; previously, the instrumentation was reliant on a single computer linked to the spacecraft itself. During this period, JPL also began developing prototypes of vehicles that might one day traverse the Martian surface.

Upon returning to campus in 1984, Albee continued his involvement in Mars missions. In his 2017 oral history, he remarked that, “Even today, we are more knowledgeable about Mars’s surface topography than we are about Earth,” primarily because the absence of oceans on Mars simplifies the study of its surface in comparison to our planet.

Following his return, he also assumed the role of dean of graduate studies, a responsibility he held for the subsequent 16 years. As graduate dean, Albee endeavored to harmonize practices across Caltech’s divisions, which were significantly divergent upon his return. He was particularly proactive in attracting diverse graduate students, a pursuit that peer institutions had already embraced by the time Albee assumed the dean’s role. In response to an influx of non-US applicants for graduate studies, Albee implemented interviews with candidates and participated on the graduate study boards for the GRE (Graduate Record Exam) and TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) examinations. He also oversaw a notable increase in female graduate school applicants.

While managing these various responsibilities for Caltech and JPL, Albee maintained a full course load in petrology and the assorted microscopic techniques necessary for rock study. For two decades, he instructed a remote-sensing course during Caltech’s spring break, taking 12 to 15 students into the California desert to observe where JPL had been conducting instrument tests for many years.

He also participated in the house committee for the Athenaeum, Caltech’s faculty club, and periodically served as the Athenaeum’s executive manager while the committee sought new leadership. The last occasion he served as executive manager was following his retirement from Caltech in 2002, during which he worked to ensure the Athenaeum complied with California labor laws and was financially self-sufficient without institutional support. “I have a certain fondness for management,” Albee expressed in 2017. “I aim to make things function effectively, to understand how to collaborate with others, and that attitude permeates all I have accomplished.” Indeed, after his retirement from Caltech, when he was “at a loss for what to do,” he became the business manager for Westminster Presbyterian Church in Pasadena.

Albee was preceded in death by his spouse Charleen.