As aging bodies deteriorate, the brain struggles to eliminate waste, a situation that researchers believe could be linked to neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, among others. Recently, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis reported they have discovered a solution to this issue by focusing on the network of vessels responsible for draining waste from the brain. They have demonstrated that revitalizing these vessels enhances memory in elderly mice.

The research, published online on March 21 in the journal Cell, paves the way for creating treatments for age-related cognitive decline that can bypass the difficulties faced by traditional medications that often fail to penetrate the blood-brain barrier to access the brain.

“The physical blood-brain barrier limits the effectiveness of therapies for neurological conditions,” stated Jonathan Kipnis, PhD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Pathology & Immunology and a BJC Investigator at WashU Medicine. “By addressing a network of vessels external to the brain that plays a vital role in brain health, we observe cognitive enhancements in mice, which opens up possibilities for developing more effective therapies to prevent or slow down cognitive decline.”

Waste clearance enhances memory

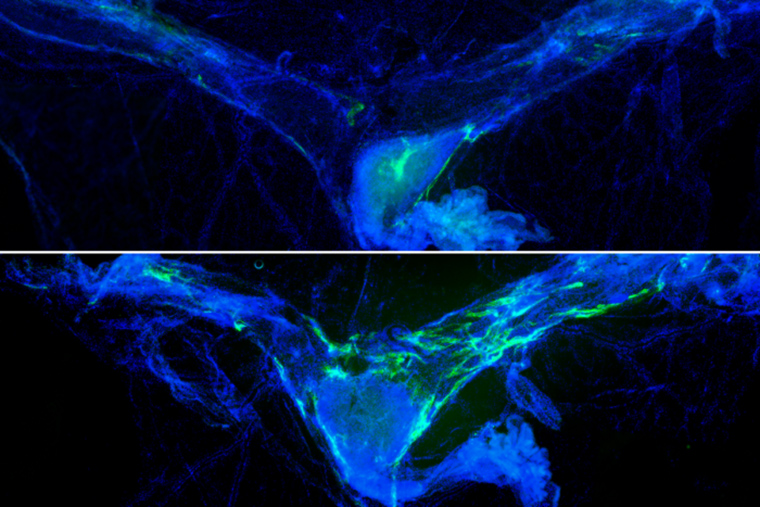

Kipnis specializes in the emerging field of neuroimmunology, which examines how the immune system influences the brain in both health and disease. A decade ago, Kipnis’ lab identified a system of vessels encircling the brain — referred to as the meningeal lymphatics — in both mice and humans that transports fluids and waste to the lymph nodes, where many immune system cells reside to watch for indicators of infection, illness, or injury. He and his team have also established that certain experimental Alzheimer’s therapies are more successful in mice when combined with a treatment that enhances the drainage of fluid and debris from the brain.

Starting around the age of 50, individuals begin to notice a reduction in brain fluid circulation as a part of normal aging. For the latest study, Kipnis teamed up with Marco Colonna, MD, the Robert Rock Belliveau, MD, Professor of Pathology, to investigate if improving the efficiency of an aging drainage system could lead to better memory.

To evaluate the memory of mice, the research team placed two identical black rods in the cage for twenty minutes for the older mice to examine. The following day, the mice were reintroduced to one of the black rods alongside a novel item, a silver rectangular prism. Mice recalling their experience with the black rod tend to spend more time engaging with the new object. However, older mice exhibited similar interest in both items.

The lead author of the new research, Kyungdeok Kim, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Kipnis lab, enhanced the functionality of the lymphatic vessels in older mice through a treatment that promotes vessel growth, facilitating greater waste removal from the brain. He discovered that older mice with revitalized lymphatic vessels engaged more with the new object — an indication of improved memory — when compared to those not receiving the treatment.

A functioning lymphatic system is essential for brain health and memory,” remarked Kim. “Therapies that support the health of the body’s waste disposal system may offer significant health advantages for an aging brain.”

Brain’s overwhelmed cleaning system

When the lymphatic system becomes so compromised that waste accumulates in the brain, the responsibility of cleaning falls to the resident immune cells, known as microglia. Unfortunately, this local cleanup crew struggles to keep pace with the accumulating debris and eventually becomes fatigued, Kipnis noted.

The research discovered that the overstressed cells emit a distress signal, an immune protein called interleukin 6, or IL-6, which impacts brain cells to encourage cognitive decline in mice with impaired lymphatic vessels. Upon examining the brains of these mice, the researchers noted an imbalance in the signals neurons received from surrounding brain cells. Specifically, neurons received fewer signals that act like noise-canceling headphones amidst the noise of neuronal communications. This imbalance, caused by heightened IL-6 levels in the brain, resulted in alterations in brain wiring and impaired proper brain functioning.

Alongside enhancing memory in the aging mice, the treatment that boosted lymphatic vessels also resulted in a reduction of IL-6 levels, rehabilitating the brain’s noise-canceling mechanism. These findings underscore the potential of improving the health of the brain’s lymphatic vessels to maintain or rejuvenate cognitive functions.

“As we celebrate the 10th anniversary of our discovery of the brain’s lymphatic system, these new results shed light on the crucial role of this system in brain health,” stated Kipnis. “Focusing on the more accessible lymphatic vessels located outside the brain may unveil an exciting new avenue in the treatment of brain disorders. Although we may not be able to restore neurons, we might enhance their optimal functioning through the modulation of meningeal lymphatic vessels.”

Kim K, Abramishvili D, Du S, Papadopoulos Z, Cao J, Herz J, Smirnov I, Thomas JL, Colonna M, Kipnis J. Meningeal lymphatics-microglia axis regulates synaptic physiology. Cell. March 21, 2025. DOI: 10.1016./j.cell.2025.02.022

This research was financed by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers AG034113 and AG078106; the BJC investigator’s program at Washington University in St. Louis; the Neuroscience Innovation Foundation; and the National Research Foundation of Korea, grant number 2021R1A6A3A14045044. The content solely reflects the authors’ views and does not necessarily represent the official stances of the NIH.

Jonathan Kipnis is a co-founder of Rho Bio and possesses patents and provisional applications related to the work described here.

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is recognized as a global leader in academic medicine, encompassing biomedical research, patient care, and educational initiatives with 2,900 faculty members. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio ranks second among U.S. medical schools and has expanded by 56% over the last seven years. In conjunction with institutional investment, WashU Medicine dedicates over $1 billion each year to groundbreaking research innovation and training. Its faculty practice consistently ranks among the top five in the nation, boasting over 1,900 faculty physicians serving at 130 locations and also affiliated with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals within BJC HealthCare. WashU Medicine has a rich legacy in MD/PhD training, recently allocating $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to prestigious training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communication sciences.

Originally published on the WashU Medicine website

The post Enhancing the brain’s waste removal system improves memory in older mice appeared first on The Source.