“`html

In May 2025, the U.S. government imposed sanctions on a Chinese individual for managing a cloud service associated with the majority of cryptocurrency fraud websites reported to the FBI. However, a recent report reveals that the accused continues to manage a variety of established accounts on American tech platforms — including Facebook, Github, PayPal, and Twitter/X.

On May 29, the U.S. Department of the Treasury declared economic sanctions against Funnull Technology Inc., a company based in the Philippines accused of supplying infrastructure for hundreds of thousands of websites involved in cryptocurrency investment frauds commonly termed as “pig butchering.” In January 2025, KrebsOnSecurity described how Funnull was conceived as a content delivery network that assisted foreign cybercriminals aiming to funnel their traffic through U.S.-based cloud providers.

The Treasury also sanctioned the alleged operator of Funnull, a 40-year-old Chinese individual named Liu “Steve” Lizhi. The government claims Funnull directly enabled financial schemes causing over $200 million in losses for Americans, linking the company’s activities to the bulk of pig butchering schemes reported to the FBI.

Normally, it’s illegal for U.S. companies or individuals to engage in transactions with individuals sanctioned by the Treasury. Nonetheless, as Mr. Lizhi’s situation illustrates, being sanctioned does not automatically lead major tech companies to eliminate their online accounts.

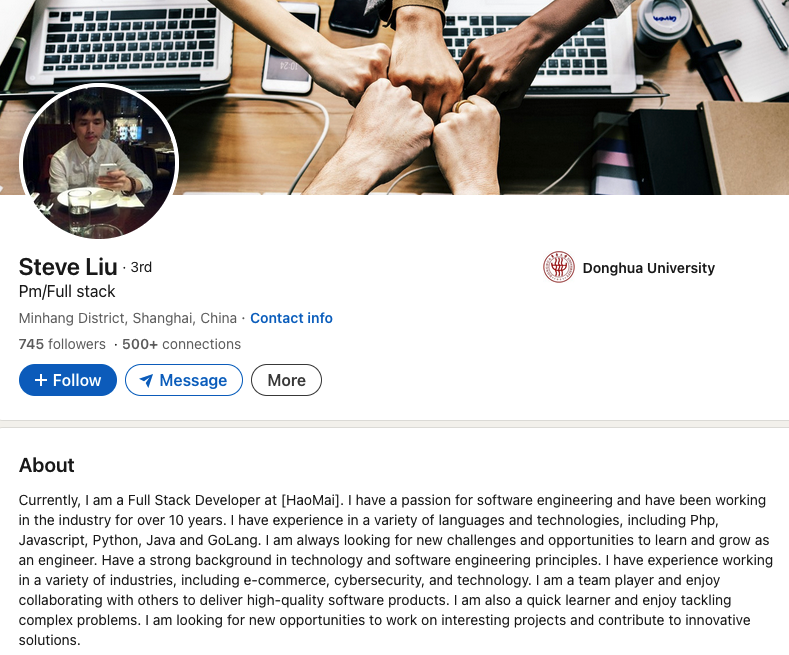

The government states that Lizhi was born on November 13, 1984, and used aliases such as “XXL4” and “Nice Lizhi.” However, Liu’s 17-year-old LinkedIn account (under the name “Liulizhi”) had amassed hundreds of followers (Lizhi’s LinkedIn profile conveniently confirms his birthday) until quite recently: The account was removed this morning, just hours after KrebsOnSecurity requested a comment from LinkedIn.

Mr. Lizhi’s LinkedIn account was deactivated within the last 24 hours, following a request for comment from KrebsOnSecurity.

In an email response, a LinkedIn representative stated that the company’s “Prohibited countries policy” indicates that LinkedIn “does not sell, license, support, or otherwise make available its Premium accounts or other paid products and services to individuals and companies sanctioned by the U.S. government.” LinkedIn did not specify whether the profile in question was a premium or free account.

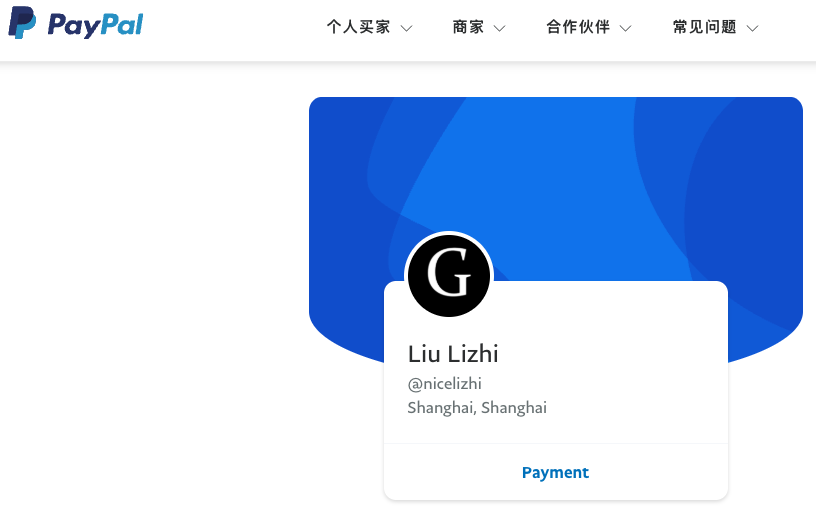

Mr. Lizhi also operates a functional PayPal account under the name Liu Lizhi and username “@nicelizhi,” another alias cited in the Treasury sanctions. PayPal did not respond to a request for comment. A 15-year-old Twitter/X account named “Lizhi” that connects to Mr. Lizhi’s personal domain is still active, although it has minimal followers and hasn’t posted in several years.

These accounts and many others were noted by the security firm Silent Push, which has been monitoring Funnull’s operations for the last year and criticizing U.S. cloud service providers like Amazon and Microsoft for not promptly severing connections with the company.

Liu Lizhi’s PayPal account.

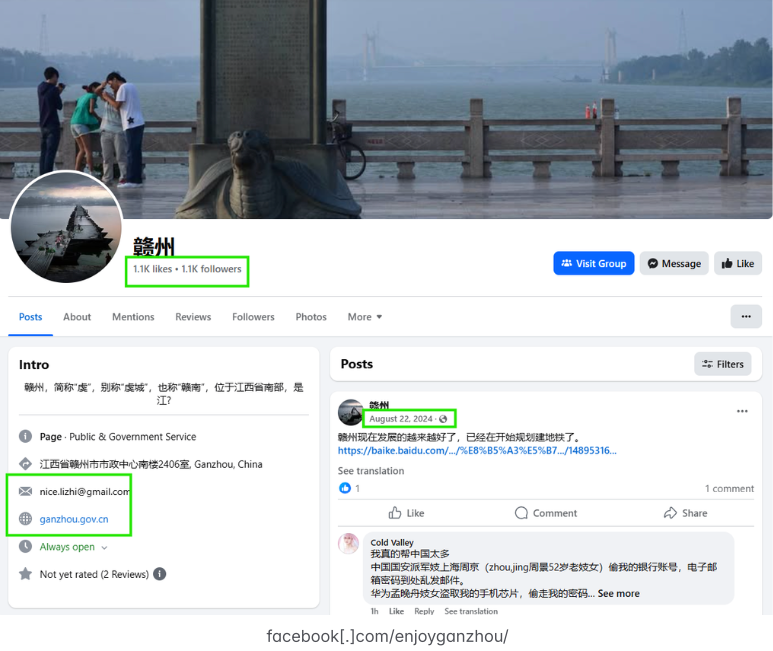

In a report released today, Silent Push discovered that Lizhi continues to operate numerous Facebook accounts and groups, including a private Facebook profile under the name Liu Lizhi. Another active Facebook account evidently associated with Lizhi is a tourism page for Ganzhou, China called “EnjoyGanzhou” that was mentioned in the Treasury Department sanctions.

“This individual is the technical administrator for the infrastructure hosting most of the scams aimed at individuals in the United States, resulting in hundreds of millions lost due to the websites he’s supported,” remarked Zach Edwards, senior threat researcher at Silent Push. “It’s astonishing that the vast majority of major tech firms haven’t taken action to terminate connections with this person.”

The FBI reports receiving nearly 150,000 complaints last year related to digital assets and $9.3 billion in losses — a 66 percent rise from the prior year. Investment scams ranked as the leading crypto-related offenses reported, with $5.8 billion in losses.

In a statement, a Meta spokesperson mentioned that the company consistently strives to fulfill its legal obligations, yet acknowledged that sanctions laws are complex and diverse.

“Sanctions are frequently targeted and do not always prohibit individuals from having a presence on our platform,” the statement asserts. “Whether any specific activity is restricted by sanctions or Meta’s Terms and Policies relies on the specific circumstances.”

Efforts to contact Mr. Lizhi via his main email accounts at Hotmail and Gmail returned as undeliverable. Similarly, his 14-year-old YouTube channel seems to have been removed recently.

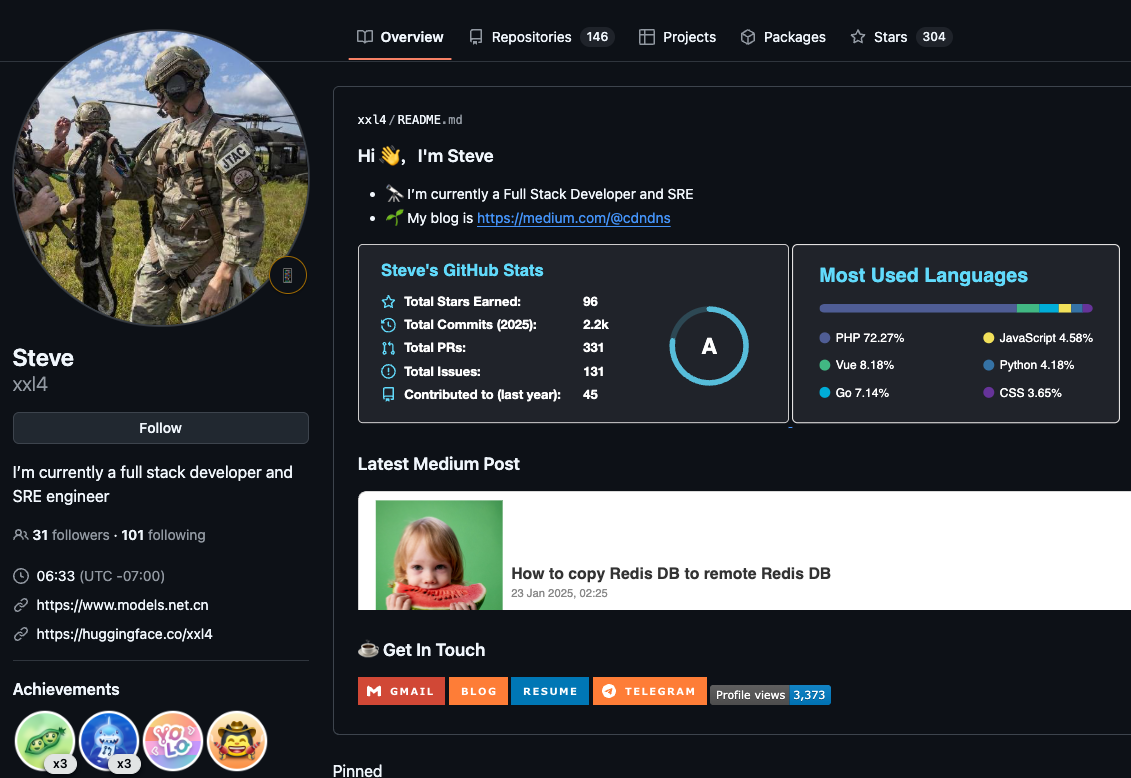

Nevertheless, anyone interested in viewing or accessing Mr. Lizhi’s 146 computer code repositories will find active GitHub accounts for him, including one registered under the NiceLizhi and XXL4 aliases mentioned in the Treasury sanctions.

One of multiple active GitHub profiles used by Liu “Steve” Lizhi, who goes by the alias XXL4 (a name listed in the Treasury sanctions for Mr. Lizhi).

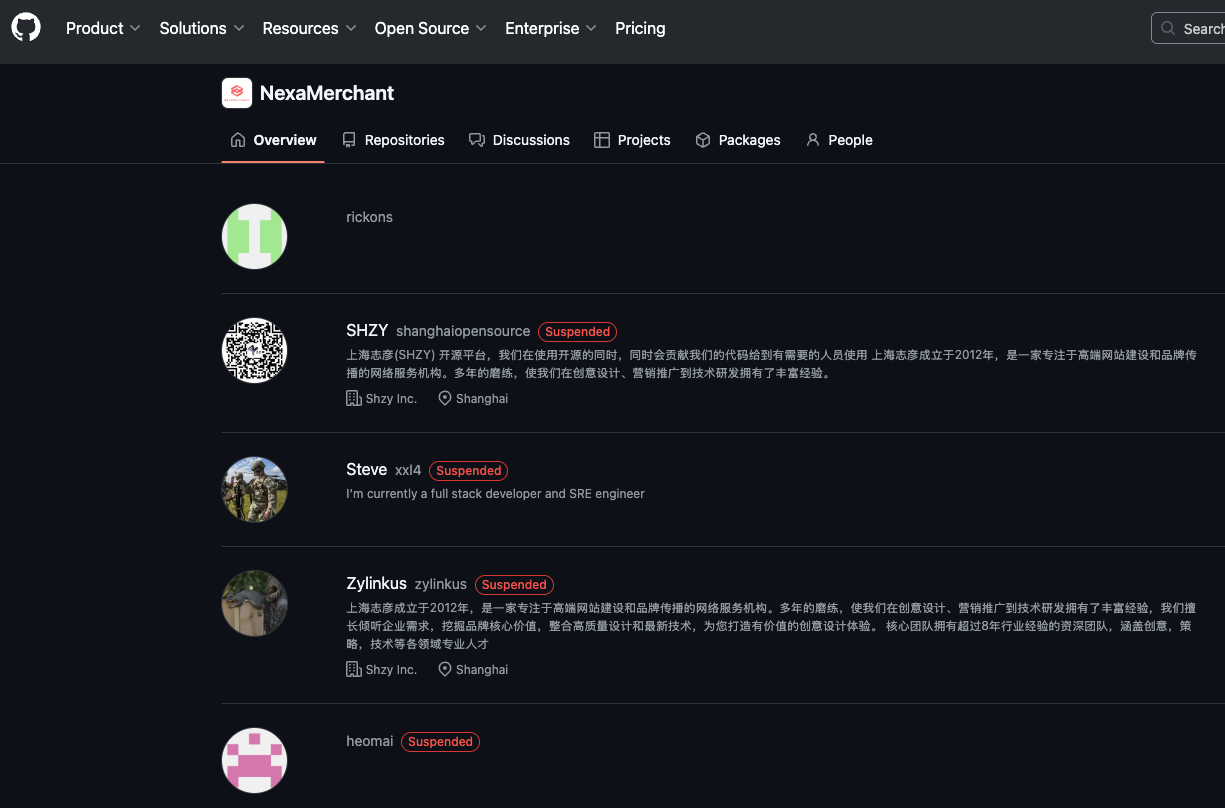

Mr. Lizhi also runs a GitHub page for an open-source e-commerce platform called NexaMerchant, which promotes itself as a payment gateway collaborating with several U.S. financial institutions. Notably, this profile’s “followers” page displays several other accounts believed to be Mr. Lizhi’s. All of the account’s followers are marked as “suspended,” even

“““html

However, that suspended notification does not appear when one navigates to those specific profiles.

In answer to inquiries, GitHub stated that it has a procedure established to recognize when users and customers are Specially Designated Nationals or other restricted or blocked entities, but instead of terminating those accounts, it locks them. As per its regulations, GitHub ensures that users and customers are not affected beyond what is mandated by law.

All follower accounts associated with the XXL4 GitHub account seem to belong to Mr. Lizhi and have been suspended by GitHub, yet their code remains accessible.

“This involves maintaining public repositories, including those for open-source projects, available and accessible to support individual communications involving developers in restricted areas,” the policy indicates. “This also signifies that GitHub will advocate for developers in sanctioned regions to receive enhanced access to the platform and complete access to the global open-source community.”

Edwards remarked that it’s commendable that GitHub has a procedure for managing sanctioned accounts; however, the process does not seem to convey risk in a clear manner, pointing out that the only indication on the locked accounts is the notification, “This repository has been archived by the owner. It is not read-only.”

“It’s a peculiar notification that fails to convey, ‘This is a sanctioned entity, refrain from forking this code or utilizing it in a production environment’,” Edwards stated.

Mark Rasch is a former federal cybercrime prosecutor currently serving as counsel for the New York City-based security consulting firm Unit 221B. Rasch remarked that when the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) places sanctions on an individual or entity, it then becomes illegal for businesses or organizations to engage in transactions with the sanctioned party.

Rasch mentioned that financial institutions possess well-developed systems to sever accounts linked to individuals who fall under OFAC sanctions, but tech corporations may be significantly less proactive—particularly regarding free accounts.

“Banks have established means of verifying [U.S. government sanctions lists] for sanctioned entities, but tech companies do not always perform that task effectively, especially for services that can be accessed simply by clicking and signing up,” Rasch explained. “It poses a potential risk and liability for the tech firms involved, but only to the degree that OFAC is prepared to enforce it.”

Liu Lizhi manages several active Facebook accounts and groups, including this one for an entity mentioned in the OFAC sanctions: The “Enjoy Ganzhou” tourism page for Ganzhou, China. Image: Silent Push.

In July 2024, Funnull acquired the domain polyfill[.]io, the longtime home of a legitimate open-source project that empowered websites to ensure that devices using outdated browsers could still present content in updated formats. After the Polyfill domain changed proprietors, a minimum of 384,000 websites were caught in a supply-chain attack redirecting visitors to harmful websites. According to Treasury, Funnull utilized the code to maneuver people to scam sites and online gambling platforms, some of which were associated with Chinese criminal money laundering operations.

The U.S. government asserts that Funnull offers domain names for websites on its purchased IP addresses, utilizing domain generation algorithms (DGAs)—programs that generate vast numbers of similar yet unique names for websites—and that it sells web design templates to cybercriminals.

“These services make it not only simpler for cybercriminals to impersonate trusted brands when creating fraudulent websites, but also enable them to swiftly shift to different domain names and IP addresses when legitimate providers seek to dismantle the websites,” states a Treasury report.

Meanwhile, Funnull appears to be transforming nearly every aspect of its business in light of the sanctions, Edwards noted.

“Whereas previously they might have utilized 60 DGA domains to obscure and reroute their traffic, we are observing many more now,” he mentioned. “They are striving to complicate their infrastructure and make it more challenging to trace, so for now they are not disappearing but rather altering their methods. And many more organizations should be holding them accountable.”

“`