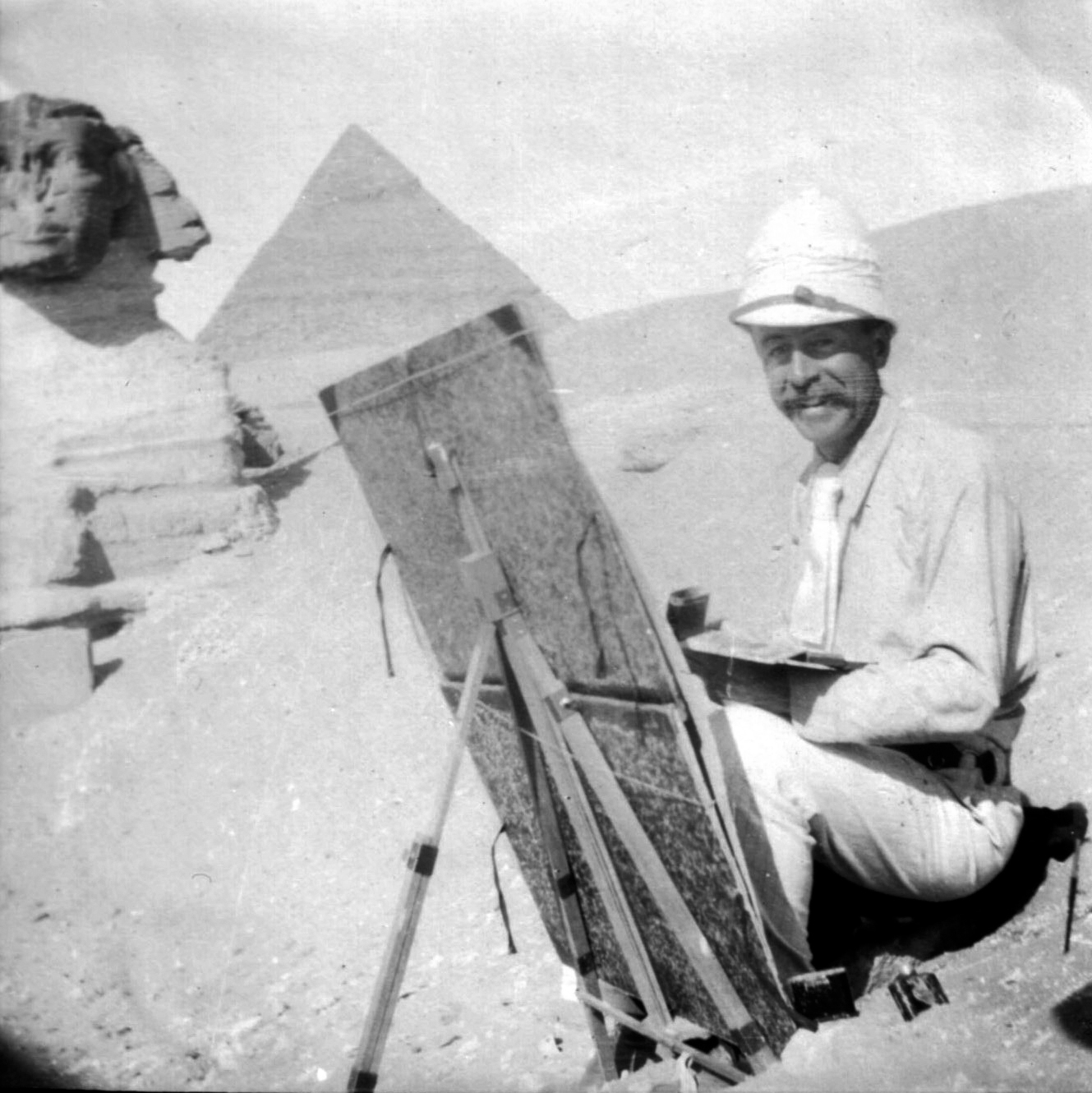

Undated image of Joseph Lindon Smith painting near the Sphinx at Giza.

Courtesy of the Dublin Historical Society

Arts & Culture

An archaeological testament that functions as art

Artist unveiled ancient Egyptian tomb’s mysteries through vibrant brushstrokes

When artist Joseph Lindon Smith reached Giza a century prior, it was following an exhilarating find: the tomb chapel of a prominent Egyptian figure named Idu, dating to between 2390 and 2361 B.C.E.

In 1925, color photography had not progressed sufficiently for archaeological purposes, so the Harvard University-Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition called upon Smith, a former portrait painter educated in Boston, to document discoveries within the Tomb of Idu. Such vividly colored depictions of archaeological locales are invaluable to researchers today.

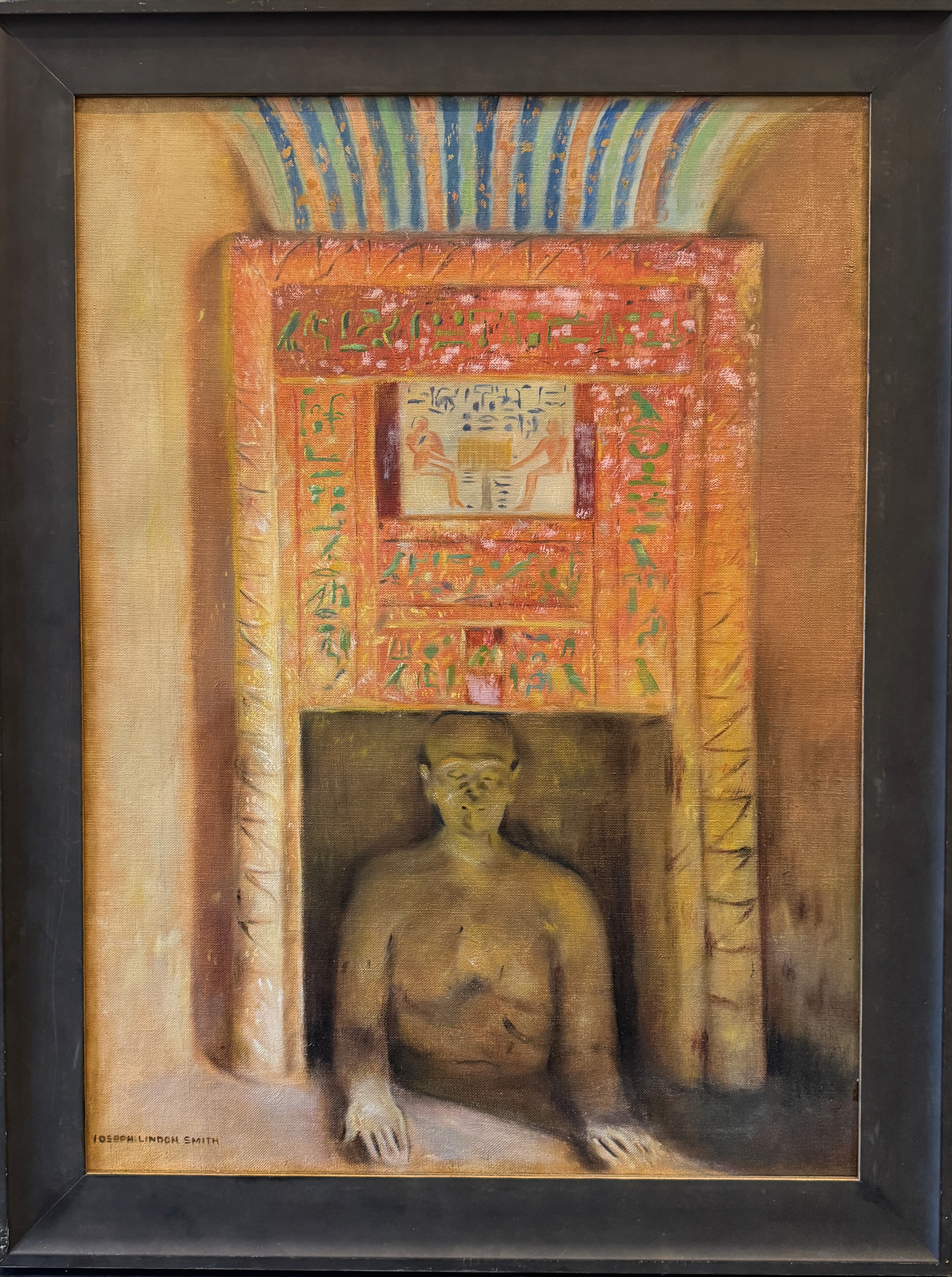

Indeed, the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East recently acquired “The Royal Scribe, Idu” — one of the approximately five artworks Smith created during his two months in the tomb — which is now exhibited in a second-floor showcase.

Peter Der Manuelian.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

“The monuments are evolving. They face deterioration, exposure to the elements; and sometimes, regrettably, there is poor treatment,” stated Peter Der Manuelian, director of the museum and Barbara Bell Professor of Egyptology. “Any historical documentation that showcases these artifacts in a different or better-preserved condition than how we perceive them currently — potentially with more vibrancy — is always appreciated.”

The artwork illustrates a statue of Idu from the waist up, set within a decorative “false door” on the western wall of the tomb chapel. The ancient Egyptians would place food offerings there, believing the spirits of the departed might enter and exit the afterlife unimpeded. Hieroglyphs above feature spells, Idu’s name, and various titles he held.

Photo of the statue of Idu emerging from the “false door.”

Courtesy of White Star Publishers

“There exist countless false doors across Egypt. What renders this one fascinating is the upper body of Idu himself, the owner of the tomb, as though he’s rising from the afterlife,” Manuelian expressed. “He even extends his hands, indicating, ‘I’m here to receive the offerings.’”

In his journal from 1925, Smith remarked on painting the Idu statue, stating “I completed my portrayal of the ‘Baksheesh’ man and commenced one of his young son to the left of the entrance.” In Arabic, “baksheesh” implies money given as gratuity, likely referring to the statue’s open hands, according to Manuelian.

The subterranean tomb chapel of Idu was revealed by Harvard-MFA archaeologists in 1925.

Courtesy of White Star Publishers

Modern researchers document excavation sites using technologies like photogrammetry to create 3D models. However, prior to the advancement of photography that could accurately capture color and detail in dim settings, archaeologists often relied on line drawings, Manuelian noted. It’s understandable that the contributions of artists such as Smith were highly esteemed by Egyptologist and Harvard Professor George A. Reisner, who managed the Harvard-MFA Expedition from 1905 until 1947 across the Giza Plateau and various sites in Egypt and Sudan.

“Reisner regarded them as both academically important and aesthetically striking,” Manuelian remarked. “He appreciated that Smith could convey three-dimensionality in his two-dimensional artwork, rendering them visually appealing while also serving as reliable documentation.”

Currently, the MFA possesses over 100 of Smith’s artworks. The Harvard Art Museums have nearly 100 of his pieces, though only a minority of these depict subjects from ancient Egypt.

“We are genuinely pleased to maintain this connection to Joseph Lindon Smith at Harvard,” Manuelian expressed. “This piece is not only aesthetically remarkable but also links to the Harvard-MFA Expedition, representing one of Smith’s Egyptian works. It truly aids in narrating that story.”