“`html

Science & Technology

A genuine butterfly impact

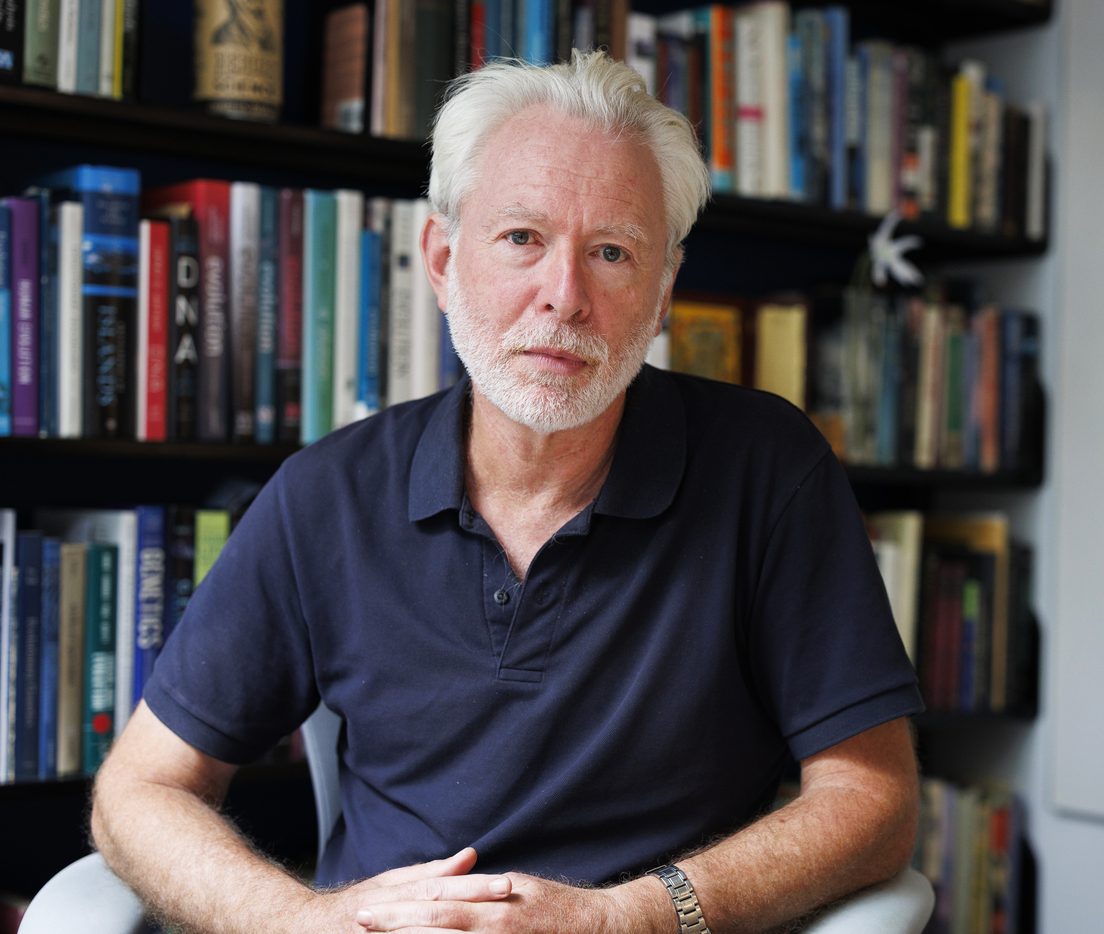

Andrew Berry.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A narrative winding through ages and continents leads to newly acknowledged species named after a Harvard biologist

This represents a story of academic fervor. It encompasses a blazing ship, a Victorian naturalist exploring jungles, a Harvard biologist, and an uncommon butterfly.

Evolutionary biologist Andrew Berry specializes in Alfred Russel Wallace, a groundbreaking evolutionist often eclipsed by Charles Darwin.

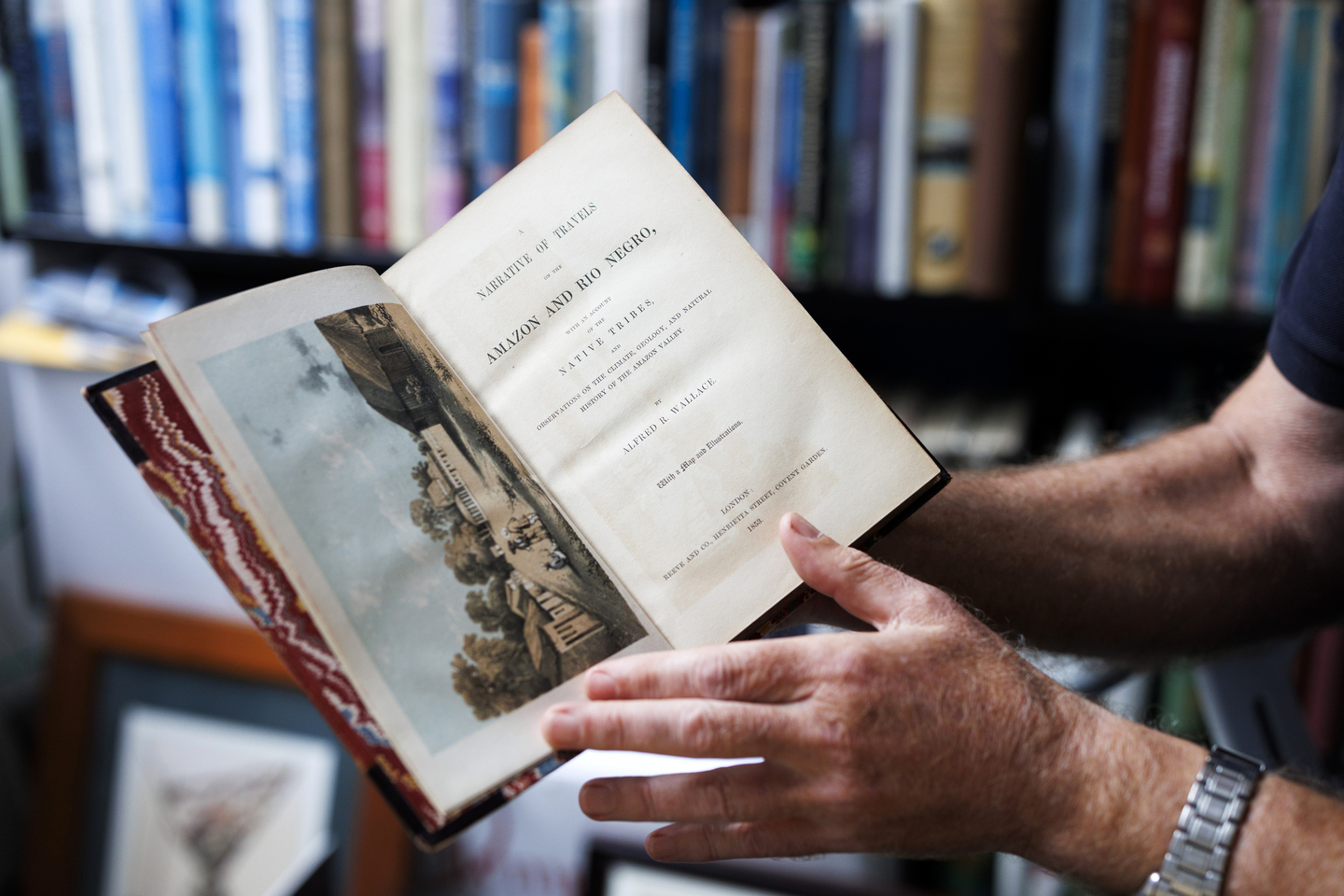

Throughout the years, he has gathered memorabilia linking him to his scientific idol, which includes a rare initial edition of travel accounts, an autographed correspondence, and an authentic map from the 19th century.

Now Berry can boast an even rarer connection: a previously-unrecognized butterfly species gathered by Wallace in the Amazon — and forgotten in museum storage for over 150 years — has been classified as a new species named in his honor.

“I’m utterly exhilarated, though it feels somewhat vain to have a little brown butterfly named for you,” Berry expressed while seated in his library-like office next to a colorful replica of his namesake butterfly, Euptychia andrewberryi. “Seeing my enthusiasm, one might understandably think, ‘Get a life, man!’”

How that tropical butterfly arrived on the desk of a witty English biologist is a scientific narrative that meanders through centuries across Brazil, the Atlantic Ocean, London, and the Harvard campus — and began for Berry with a writing task.

Alfred Russel Wallace.

Photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Wallace, born in Wales in 1823, proposed his own theory of evolution through natural selection concurrently with Charles Darwin in 1858. Due to several factors, Darwin earned recognition as the father of evolutionary biology, while Wallace became known as a secondary figure.

Nonetheless, Wallace was an innovative naturalist in his own right, credited with numerous significant scientific contributions. He established the discipline of biogeography and identified a distinction in fauna that set apart Asia from Australia, New Guinea, and the Pacific islands — a boundary now referred to as the “Wallace Line.”

In 1848, Wallace and fellow entomologist Henry Walter Bates set sail for Brazil to examine the Amazon and collect insects and other species.

Four years later, Wallace was en route back to England when his vessel caught fire during the Atlantic journey, resulting in the loss of nearly all his collections. Wallace and his surviving companions endured 10 days in lifeboats before rescue.

Fortunately, Wallace had previously shipped some crates of specimens before the tragic voyage. Amongst these were a few butterflies from Brazil.

Fast-forward to the present century. Shinichi Nakahara, an associate in entomology at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, is a specialist in butterfly taxonomy and co-author of the vividly-illustrated guidebook “Butterflies of the World.”

He dedicated a decade to studying a monograph on the genus Euptychia, a group of butterflies from South America and Central America. While examining collections worldwide, he discovered the butterflies collected by Wallace and Bates at the Museum of Natural History in London.

Andrew Berry investigates the butterfly collections.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Life-sized replica of the vibrant butterfly Euptychia andrewberryi, also known as “Andrew Berry’s Black-eyed Satyr” on his desk.

Butterflies in the collections at the MCZ.

“““html

“A Chronicle of Journeys on the Amazon and Rio Negro” by Alfred R. Wallace.

Several of those samples were categorized as the pitch brown black-eyed satyr (Euptychia picea). However, Nakahara identified that five were morphologically unique and constituted a new species, one hitherto unrecognized by science.

He had an excellent candidate for a new title — a delightful persona who had provided him with a deeper understanding of Wallace.

Introducing Berry, who currently serves as the assistant head tutor for integrative biology and is a lecturer on organismic and evolutionary biology.

Berry has held numerous roles as a biologist. He pursued large rodents through the forests of New Guinea, examined the genetics of fruit flies, and (keep in mind this is not an exact ranking) mentored countless undergraduate biology students. He co-authored a publication with the Nobel Prize-winning geneticist James Watson and has extensively written on the history of science.

As the millennium approached, he was serendipitously tasked with writing about Wallace for the London Review of Books, which captivated him. He subsequently penned various essays on Wallace and published a compilation of his works.

“You can’t engage with Wallace’s writings and not be enchanted by him, partly because he’s such an exceptional author,” remarked Berry. “Then there’s the underdog aspect — here’s the individual who co-discovered the theory that we celebrate, yet he essentially vanished from public awareness.”

“You can’t engage with Wallace’s writings and not be enchanted by him, partly because he’s such an exceptional author. Then there’s the underdog aspect — here’s the individual who co-discovered the theory that we celebrate, yet he essentially vanished from public awareness.”

Andrew Berry

Nakahara believed that such an academic warranted his own species.

Upon his initial arrival in Cambridge, Nakahara resided at the home of his faculty mentor, Naomi Pierce, curator of lepidoptera in the MCZ and Sidney A. and John H. Hessel Professor of Biology, who also happens to be wed to Berry.

Nakahara found that breakfast at the household included ample discussions surrounding Wallace.

“His contribution lies in bringing Wallace to the forefront, since Wallace is someone who’s renowned for not being well-known,” Nakahara stated. “Andrew excels at articulating the significance of these early naturalists and Victorian biologists, and he is very engaging.”

Having a butterfly named in his honor — even better, one collected by Wallace and Bates — makes Berry’s heart leap. One student, Amanda Dynak ’24, crafted a model of his namesake species as a present.

“Andrew is absolutely thrilled about it,” said Pierce with a laugh. “I just think it’s a remarkable narrative, as Andrew is deeply committed to Alfred Russel Wallace and has been for quite some time — in fact, long before Wallace gained popularity.”

However, Berry cannot assert any particular distinction in his household. His wife already boasts three species named after her, including a zombie-ant fungus, a brain-invading parasite.

“She’s significantly ahead of me,” he remarked.

“`