“`html

From the very first moment we met over lunch that day, there was an instant bond between us, which we duly recognized, as was customary among adults, for just a brief moment at our farewells. I’ve cherished that instant with joy and will continue to do so, as I hope you might as well. Perhaps it’s for the best – although I don’t entirely believe this – that we lack the means to manifest all of this into reality; contemplate the harm we are sparing each other!

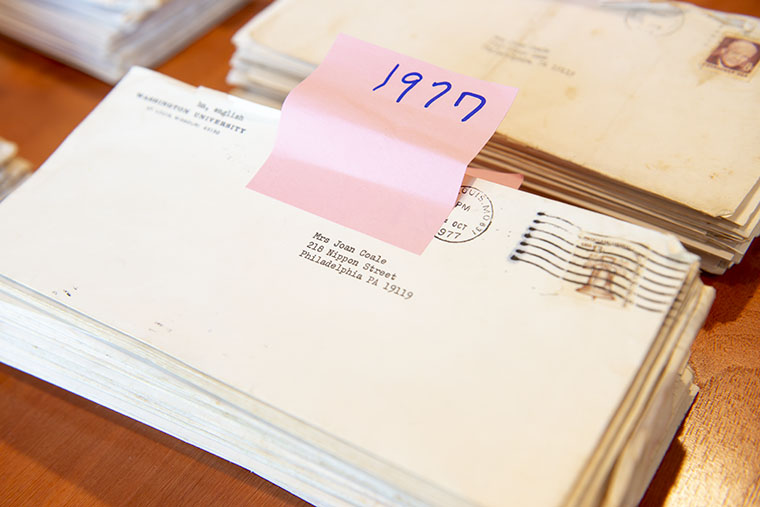

The letter, dated Jan. 7, 1972, signified not an end, but the inception of a clandestine romance between the renowned poet Howard Nemerov and Joan Coale from Philadelphia. Throughout nearly two decades, Nemerov, who served on the faculty at Washington University from 1969 until 1991, ultimately holding the title of Edward Mallinckrodt Distinguished University Professor of English and esteemed poet in residence, penned 461 letters to Coale. The final one was delivered in 1990, approximately a year prior to Nemerov’s passing from cancer at age 71.

These letters, along with additional materials, have now been integrated into the WashU Libraries’ Modern Literature Collection, which features The Howard Nemerov Papers, an extensive collection featuring Nemerov’s correspondence with notable literary figures, drafts of poetry, recordings from readings, memorabilia from various appearances nationwide, and much beyond. Joel Minor, curator of the Modern Literature Collection and manuscripts, is examining the letters to uncover what additional insights we might gain about Nemerov, who received both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize in 1978, and served as U.S. poet laureate from 1988 to 1990.

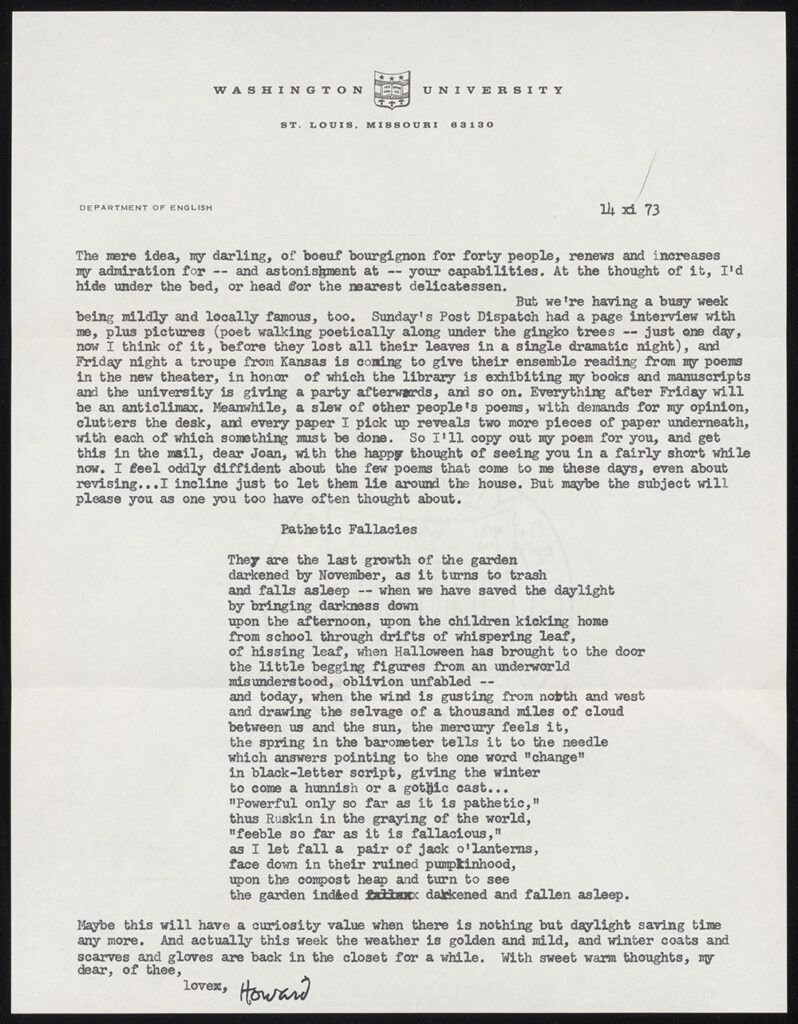

In one correspondence, Nemerov contemplates the photography of his illustrious sister, Diane Arbus: D’s work is undeniably extraordinary, yet at times it feels as if it’s suggesting that either images like these should not be, or perhaps that people like us shouldn’t exist. Or maybe even God? In another, he conveys the purpose behind his art: I persist in asserting that poetry endeavors to articulate the silence, to perceive the unseen, and to express the inexpressible.

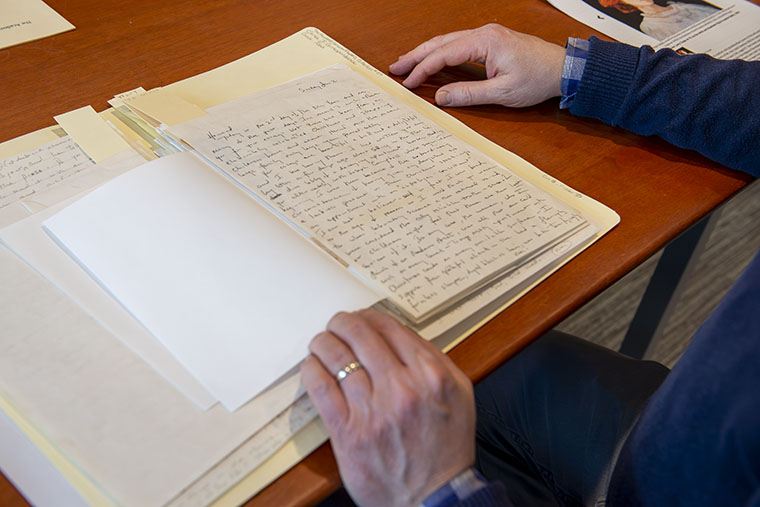

Other letters feature drafts of unpublished poems; insights on Dante, Proust, and Shakespeare; and updates on his writing journey — or its absence. Coale seemingly wrote Nemerov as many, if not more, letters, though only 24 are present in the Howard Nemerov Papers.

“In addition to a romantic connection, there’s also a significant intellectual bond,” Minor states. “The letters contained discussions. He frequently responded to her thoughts regarding art and literature as well as personal matters such as issues related to parenthood. He valued her opinions and emotional states, and he sincerely treasured her counsel and support.”

A revelation

Minor became aware of the letters this past winter after receiving an unexpected email from Coale’s son, who shares the same name, Howard. In the message, he disclosed that his mother had passed away at age 97 and desired the letters to be donated to WashU after her death.

“The bond was a secret between them and was exceptionally well preserved,” Coale mentioned in the email. “Moreover, as my mother told me on numerous occasions, Howard aimed to keep his letters as discreet and as unromantic as possible, being mindful of posterity, and, most critically, to safeguard his family.”

“That initial email from Howard [Coale]— it was a revelation,” Minor recalls. “This is what I refer to when I say you can never predict who might reach out to you. It’s the thrilling aspect of the job.”

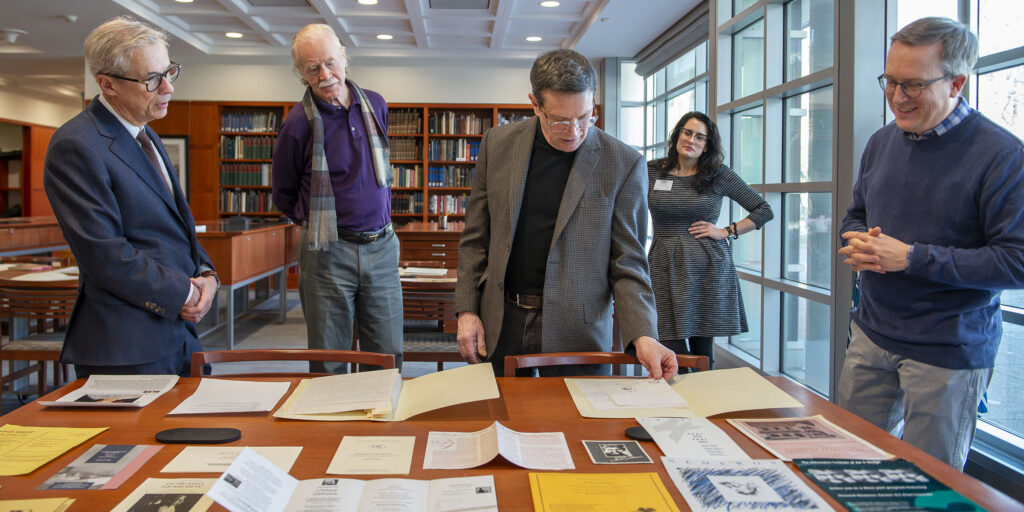

On Feb. 13, Coale journeyed to St. Louis to present the letters to WashU curators and scholars at Olin Library. Art historian Alex Nemerov, the Carl and Marilynn Thoma Provostial Professor in the Arts and Humanities at Stanford University and Nemerov’s middle son, was also present at the event.

“Firstly, I just need to verify that you are not my brother,” Nemerov joked as he met Coale for the first time.

Alex Nemerov never held any illusions regarding his father and had long suspected that he had engaged in extramarital affairs during his travels for readings and conferences. He cannot determine whether it is better or worse that his father was unfaithful to his mother with one individual versus many; only that those years at home were “chaotic.”

“This beautiful romance between my father and this woman had far-reaching repercussions that negatively impacted my life,” Nemerov remarks. “This discovery places everything into clearer perspective, but I don’t wish to delve into accusations or resentment. I’m aiming to approach the entire situation with forgiveness and understanding.”

Alex Nemerov was genuinely pleased to meet Howard Coale and learn more about Joan, a divorced mother of four who cherished James Joyce, Johann Sebastian Bach, and art. Still, he doubts his father ever intended for these letters — some of which are indeed affectionate — to be made public.

“This is certainly not how he would have wanted it, not even close,” Nemerov asserts. “My father…

“““html

could have been the quintessential individual to assert that the background story and his existence are irrelevant. It’s the poetry itself that matters.”

Nevertheless, the correspondence might attract fresh interest towards a literary luminary who could be as narcissistic as he was reserved.

“My father isn’t really a recognizable name anymore, not in the truest sense, which is neither just nor fortunate. One doesn’t encounter his works in bookstores or a Library of America compilation of his poetry,” Nemerov remarks. “For him to possibly gain renewed recognition in this manner — one must acknowledge the irony.”

Meanwhile, research continues on the Joan Coale Collection of Howard Nemerov Correspondence, which comprises 461 letters and additional materials such as drafts of Nemerov’s poetry, articles, and invitations sent by Nemerov to Coale. Minor is currently engaged in cataloging the letters, and the collection is accessible to the public.

As for Alex Nemerov, he hasn’t yet perused the letters, but he intends to. There was, however, one letter he did read during the flight to St. Louis to meet Coale. In it, his father conveys to Joan Coale that she would appreciate Alex, describing him as “such a compassionate soul, despite his serious demeanor.”

“Everyone I mention that to here just laughs,” Nemerov shares, “because it seems so precise. That truly softened me in a single sentence regarding the entirety of it. That was a profoundly tender moment for me, feeling affirmed and cherished by my father.”

‘Poet strolling poetically beneath the ginkgo trees …’

The post A man of letters appeared first on The Source.

“`