They’re eerie and they’re whimsical. Enigmatic and eerie. Some may even claim they’re all together quirky.

However, unlike the adored and eccentric Addams Family, insects are certainly less desired in our households.

While butterflies and bees usually bask in public affection, less conventionally appealing critters such as cicadas and Joro spiders are ignored—or, even worse, crushed.

“I believe insect preservation is one of the most disregarded sectors of conservation biology,” states William Snyder, an entomology professor at the University of Georgia’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES). “They’re not cuddly; few insect species possess charm. Yet insects play a fundamental role in numerous ecosystems.”

Why should it matter to you? To begin with, insects are ubiquitous.

Insects alone constitute more than half of all animal species on the planet. Include other terrestrial arthropods, like arachnids, centipedes, and millipedes, and you’re confronted with millions of species, many of which remain undocumented, as per the U.S. National Park Service.

But don’t let their staggering populations alarm you too much. Many of these bugs—like those you’ll encounter in the subsequent sections—are harmless or even advantageous. And they require our assistance to continue fulfilling their vital roles.

They fertilize our fruits and vegetables, aid in the decomposition of organic waste that would otherwise accumulate, act as a crucial food source for various other organisms, and so much more.

Insects, arachnids, and other creatures. Oh my.

Ever ponder what distinguishes an insect from a bug? Or perhaps you’re more inclined to think, “I don’t care what it’s called. Just keep it away from me”? Here are a couple of essential tips to discern the difference.

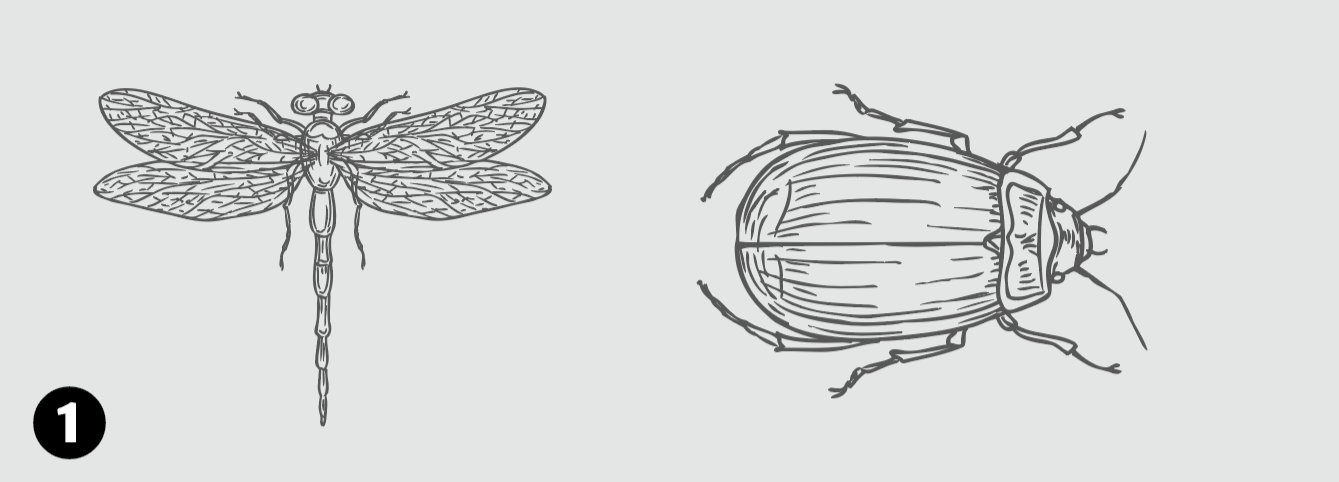

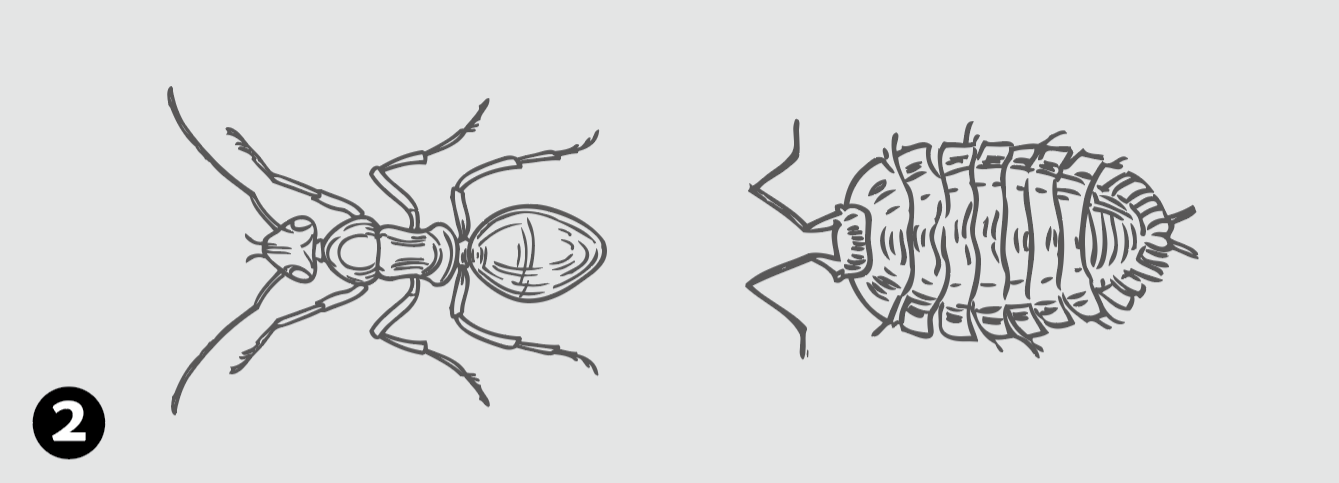

1. Quantity of body segments

Insects possess three: a head, a thorax, and an abdomen. It can sometimes be tricky to determine where one segment finishes and another starts. For instance, the dragonfly has distinctly defined segments. In contrast, the segments on beetles, such as ladybugs, are a bit more challenging to notice due to their wings overlapping a portion of their body. Meanwhile, an arachnid, like a spider or scorpion, features two body sections and lacks the antennae characteristic of true insects.

2. Quantity of legs

This is where it becomes a tad more unsettling. Insects generally have three pairs of legs, totaling six. This means creatures like centipedes, spiders, and roly-polys (also known as pill bugs) actually aren’t categorized as insects. Instead, think about ants, bees, and flies. You probably aren’t counting the legs of the mosquito that just landed on your arm before swatting it, but if you did, you’d find that this blood-sucking pest also sports six legs.

An Insect Cataclysm?

Insects are some of nature’s most potent survivors in the face of change. Whether in response to shifts in their surroundings or climate, many species demonstrate impressive adaptability.

Consider the Joro spider.

Having traveled to the U.S. via shipping containers from Asia in the 2010s, the Joro spider arrived in a new environment on the East Coast. This vividly colored yellow-and-black arachnid is capitalizing on its move, expanding from a handful of spiders here and there to being found amidst powerlines, atop stoplights, and even suspended above gas pumps.

Joros exhibit a remarkable ability to adjust to urban settings and prosper where other spiders struggle. This flexibility leads researchers to believe these invasive species are set to remain. (Don’t be concerned, though. They are mostly harmless.)

While there are genuine worries regarding the health of the insect population, the reality is more intricate than mere speculations of a widespread insect extinction suggest.

“On one hand, you hear that all insects are on the verge of disappearance,” Snyder notes. “Conversely, you hear that mosquitoes responsible for malaria are spreading more widely and that agricultural pests are on the rise due to shifting climates.”

“What is clear is that while some insects may be adversely affected, others might benefit. To understand the true dynamics of the situation, you need to consider the broader perspective over a more extended period and across continental scales.”

Royalty Among Butterflies

Insects also exhibit remarkable resilience, consistently bouncing back from adverse weather occurrences or disease outbreaks.

Monarch butterflies serve as an exemplary illustration of how an insect facing challenges in one part of the globe can flourish elsewhere.

In recent years, researchers have grown increasingly worried about the well-known monarchs, closely monitoring as the numbers of migratory monarchs arriving at their winter havens have steadily declined.

Research from UGA scientists indicates that summer populations of monarchs in North America have remained relatively stable over the past quarter-century. These breeding groups may help offset the species’ losses during their annual migration southward.

Nevertheless, worries about the insect’s migration endure, with recent investigations spearheaded by Andy Davis, an assistant research scientist at UGA’s Odum School of Ecology, and Snyder revealing that monarchs are perishing at alarmingly high rates as they journey thousands of miles each winter to locations in Mexico.

Confronting a growingly prevalent parasite called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (or OE for brevity), diminishing habitats, rising insecticides, and fluctuating weather patterns, monarchs seem to be facing a daunting challenge. However, it’s not an insurmountable one.

“Monarch migration is experiencing difficulties,” states Sonia Altizer, the Martha Odum Distinguished Professor of Ecology. “However, a single female monarch has the potential to lay 1,000 or more eggs, indicating their potential for recovery. They’re quite resilient as far as insects go.”

Sonia Altizer didn’t initially aim to study monarch butterflies. But upon discovering the species afflicted by a little-studied parasite, she recognized her true calling. (Photo by Andrew Davis Tucker/UGA)

It’s common knowledge that monarchs are in a precarious position, and many wish to lend a hand. Regrettably, numerous attempts to “save the monarchs” might be detrimental to their survival.

Home gardeners understand that milkweed supplies nourishment for monarchs when they are in their caterpillar phase and nectar

for grown-ups. However, they might not be aware of the significant contrast between the growing periods of our indigenous milkweeds and those of non-indigenous tropical milkweeds.

Indigenous milkweed perishes in the autumn and winter, prompting monarchs to commence their journey southward in a non-reproductive state, which is vital for their survival during their five-month period in Mexico. Tropical milkweeds continue to bloom until they are affected by a severe frost, providing a continual source for monarchs to feed and breed when they should be migrating and wintering.

“They spot this milkweed, and it’s like a treat for them,” Altizer remarks. “They simply cannot resist. Some of those monarchs migrating south might abandon their journey and start reproducing again. If they can, they will continue this throughout the winter.”

This accelerates the transmission of the OE parasite, which transfers from adults to eggs and larvae, and the level of infection increases with each generation. Instead of deterring gardeners from contributing to the cause, researchers encourage them to cultivate plants that will assist monarchs in maintaining their migration.

“We want individuals to plant indigenous milkweed and nectar plants for butterflies,” Altizer expresses. “But it must be carried out in a manner that mimics natural environments.”

Becoming Part of the 10% Club

It’s not just butterflies that would gain from this strategy. Most—if not all—insects thrive in natural ecosystems, and it wouldn’t require much effort to make a difference.

Jennifer Berry was a comedian and actress. But when she decided to return to school at UGA, it was just a couple of entomology classes with Professor Keith Delaplane that made her realize she wanted to focus her career on bees.

“I know the public cherishes their lawns, but what if everyone could give up around 10% of their yard to help establish wildlife corridors?” queries Jennifer Berry BSA ’98, MS ’00, PhD ’24, an entomologist and outreach specialist with CAES and UGA Cooperative Extension. The corridors don’t have to be elaborate. In fact, making a significant impact could simply involve planting a single tree.

“Trees are especially beneficial for honeybees,” asserts Lewis Bartlett, an assistant professor of entomology in both the Odum School and CAES at UGA. “A few mature tulip poplars will provide a lot more than expansive fields of clover. These substantial landscaping trees are absolutely essential to insect vitality.”

For some of our native bees that can only travel around 100 feet, having these small areas of habitat and nourishment could be the difference between a flourishing colony of pollinators and extinction.

Recently, Berry has been collaborating with Scott Griffith, the assistant manager of UGA’s golf course and associate director of agronomy, to transform unused spaces on the award-winning public course into pollinator habitats featuring trees, shrubs, and wildflowers.

“If we can implement this at a golf course, we can undoubtedly do it in anyone’s back or front yard,” says Berry.

Lewis Bartlett has always had a fondness for insects, especially bees. He refers to bumblebees as the “Tauruses of the bee world, slow to anger but very slow to forgive,” and states that while carpenter bees “may look like they could harm you, they’re actually just large cinnamon rolls.”

Maintain Bee Health

Bees aren’t the only insects suffering from parasites and disease outbreaks. Nevertheless, there are reasons to remain optimistic.

Groundbreaking discoveries include the first-ever bee vaccine from the UGA Innovation District’s Dalan Animal Health in collaboration with CAES, the UGA Bee Lab, and the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Moreover, initiatives led by UGA researchers such as Project Monarch Health, a citizen science initiative that safely samples wild monarch butterflies to monitor the spread of parasites, and Joro Watch, which tracks the spread and expansion of the Joro spider, help safeguard our creepy crawly companions and inform the public about the vital roles insects and other bugs play in our ecosystem.

“Insects and spiders are so distinct from us,” Altizer explains. “Their bodies vary. Their brains and sensory systems function differently. And perhaps that is one reason many individuals are deterred by insects: because they are so dissimilar and may appear odd. However, for me, this peculiarity makes them incredibly captivating.”

“I wish I could perceive what a butterfly perceives and feel what a butterfly feels, as it would enable me to answer so many questions if I understood how they experienced their environment. However, one thing I do know is that it’s considerably different from how we perceive the world.”

The post A Bug’s Life appeared first on UGA Today.