“`html

In 1989, New York City inaugurated a new prison. But not on solid ground. The city rented a barge, then referred to as the “Bibby Resolution,” which had been topped with five tiers of containers converted into living quarters, and secured it in the East River. For five years, the vessel accommodated detainees.

A floating correctional facility is an oddity. Yet, the entire saga of this barge is intriguing. Constructed in 1979 in Sweden, it housed British soldiers during the Falkland Islands conflict with Argentina, transformed into housing for Volkswagen workers in West Germany, was sent to New York, served as a detention center off the coast of England, and finally was utilized as worker accommodations for oil personnel off the coast of Nigeria. The barge has undergone nine name changes, had numerous owners, and flown the flags of five different nations.

In this solitary vessel, we can observe many currents: globalization, the fleeting nature of economic activity, and the ambiguous domain of transactions many analysts and commentators label “the offshore,” the loosely regulated arena of economic endeavors that fosters short-term initiatives.

“The offshore offers a swift and potentially economical remedy to a crisis,” states MIT instructor Ian Kumekawa. “It is not a sustainable solution. The narrative of the barge exemplifies it being utilized as a quick fix in various crises. Over time, these makeshift solutions become standard, and individuals acclimatize to them, coming to expect that this is the way the world functions.”

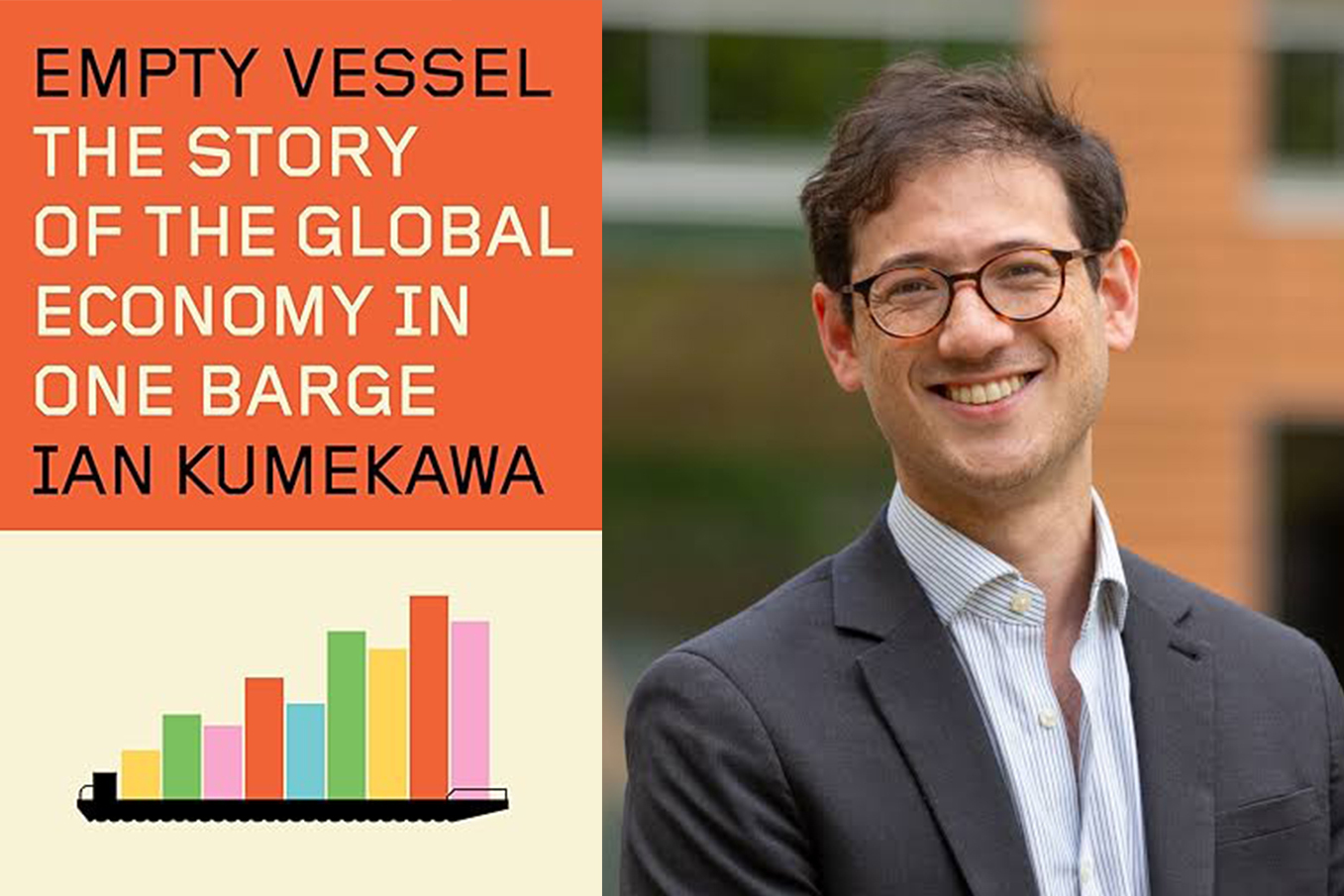

Currently, Kumekawa, a historian who began lecturing at MIT earlier this year, investigates the vessel’s comprehensive history in “Empty Vessel: The Global Economy in One Barge,” which was recently released by Knopf and John Murray. In this work, he tracks the barge’s path and the numerous economic and geopolitical shifts that shaped the ship’s unique deployments around the globe.

“The book revolves around a barge, but it’s also focused on the evolving, emergent offshore realm, where one can observe these layers of globalization, financialization, privatization, and the erosion of territoriality and orders,” Kumekawa explains. “The barge serves as a medium through which I can narrate the story of these interconnected layers.”

“Never intended to be everlasting”

Kumekawa initially discovered the vessel several years ago; New York City procured another floating detention facility in the 1990s, prompting Kumekawa to delve into the history of the earlier jail ship, the former “Bibby Resolution,” from the 1990s. The more information he unearthed about its unique history, the greater his curiosity grew.

“You begin tugging on a thread, and you realize you can keep pulling,” Kumekawa shares.

The barge Kumekawa follows in his book was constructed in Sweden in 1979 as the “Balder Scapa.” Even at that time, commerce was significantly globalized: The vessel was commissioned by a Norwegian shell corporation, with negotiations led by an expatriate Swedish shipping agent whose enterprise was registered in Panama and utilized a Miami bank.

The barge was created at a pivotal moment following the economic downturn and oil crises of the 1970s. Manufacturing was on the brink of decline in both Western Europe and the U.S.; approximately half as many individuals are now employed in manufacturing in these regions compared to 1960. Corporations were seeking cheaper global locations for production, reinforcing the perception that economic activity had become less stable in any particular area.

The barge became a part of this transience. The five-story accommodation block was added in the early 1980s; in 1983, it was re-registered in the UK and dispatched to the Falkland Islands as troop accommodations named the “COASTEL 3.” Subsequently, it was re-registered in the Bahamas and sent to Emden, West Germany, as lodging for Volkswagen employees. The vessel then served as inmate housing — first in New York, then off the coast of England from 1997 to 2005. By 2010, it had been re-re-re-registered in St. Vincent and Grenadines and was housing oil workers off the coast of Nigeria.

“Globalization is more about movement than about stocks, and the barge exemplifies that,” Kumekawa states. “It’s continuously on the move and was never intended to be a permanent fixture. It’s acknowledged that individuals will pass through.”

As Kumekawa elaborates in his book, this sentiment of social dislocation coincided with the diminishing capacity of the state, as numerous governments increasingly encouraged corporations to engage in globalized production and lightly regulated financial activities across multiple jurisdictions, hoping it would boost growth. And it has, albeit with unresolved inquiries regarding who benefits, the social dislocation of workers, and more.

“In a certain sense, it’s not a diminishment of state power at all,” Kumekawa asserts. “These states are making very proactive choices to utilize offshore tools, to bypass certain obstacles.” He continues: “What occurs in the 1970s and certainly in the 1980s is that the offshore solidifies as a distinct entity and did not exist in the same manner even in the 1950s and 1960s. There are financial interests at play, as well as political interests.”

Abstract forces, tangible materials, and people

Kumekawa is a scholar with a deep interest in economic history; his previous work, “The First Serious Optimist: A.C. Pigou and the Birth of Welfare Economics,” was published in 2017. This upcoming fall, Kumekawa will co-teach a course on the nexus between economics and history alongside MIT economists Abhijit Banerjee and Jacob Moscona.

Working on “Empty Vessel” also required that Kumekawa employ a variety of research methodologies, ranging from archival studies to journalistic conversations with individuals familiar with the vessel.

“I engaged in a wonderful series of discussions with the individual who served as the last bargemaster,” Kumekawa notes. “He effectively steered the vessel for many years. He was keenly aware of all the dynamics at play — the oil market, accommodation prices, regulations, and the fact that no one had reinforced the frame.”

“Empty Vessel” has already garnered critical praise. In a review for The New York Times, Jennifer Szalai remarks that this “elegant and enlightening book is an impressive achievement.”

For his part, Kumekawa drew inspiration from a variety of texts regarding ships, voyages, commerce, and exploration, recognizing that these vessels harbor stories and vignettes that illuminate the broader world.

“Ships serve as excellent devices connecting the global and local realms,” he explains. By employing the barge as the organizing theme of his book, Kumekawa concludes, “it renders a multitude of abstract processes exceedingly tangible. The offshore itself is an abstraction, but it remains entirely reliant on physical infrastructure and actual locations. My aspiration for the book is that it accentuates the material aspect of these abstract global forces.”

“`