“`html

Everyone experiences migraines. However, not everyone endures episodes of cluster headaches, a crippling condition causing severe discomfort that can persist for an hour or two. Cluster headache episodes occur in groups — hence the title — and leave individuals in utter distress, incapacitated. Slightly less than 1 percent of the U.S. populace struggles with cluster headaches.

But this merely scratches the surface of the issue. What is it genuinely like to endure a cluster headache?

“The discomfort of a cluster headache is so intense that you can’t remain still,” states MIT-based science writer Tom Zeller, who has been afflicted by them for decades. “I’d compare it to placing your hand on a scorching burner, except you can’t remove your hand for an hour or so. Each headache feels like a crisis. You need to run or pace or sway. Imagine another agony you had to dance through, yet it simply won’t cease. It’s that degree of severity, and it all takes place within your head.”

Then there’s the pain from migraine headaches, which appears somewhat less intense than a cluster episode, but remains longer-lasting and similarly incapacitating. Migraine episodes can be accompanied by extreme light and sound sensitivity, visual disturbances, and nausea, among various neurological symptoms, leaving sufferers confined to dim rooms for hours or even days. Approximately 1.2 billion individuals globally, including 40 million in the U.S., grapple with migraine episodes.

These are far from obscure issues. Yet, we remain uncertain about why migraine and cluster headache disorders manifest, nor how to address them. Headaches have never been a focal point within contemporary medical investigation. How can something so prevalent be so neglected?

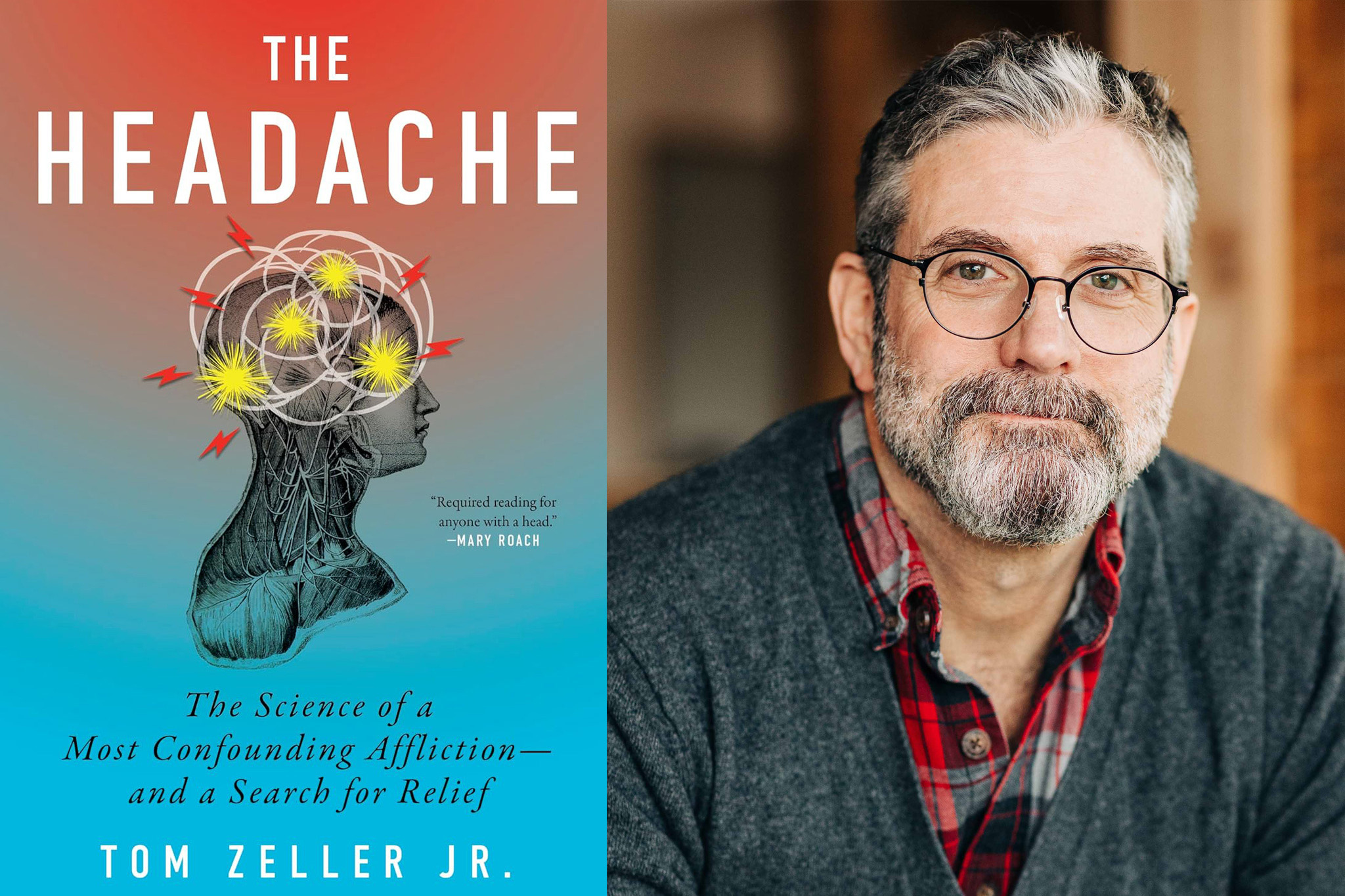

Currently, Zeller explores these concerns in a captivating book, “The Headache: The Science of a Most Confounding Affliction — and a Search for Relief,” published this summer by Mariner Books. Zeller serves as the editor-in-chief and co-founder of Undark, a digital publication on science and society produced by the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT.

One term, yet distinct syndromes

“The Headache,” which marks Zeller’s debut publication, integrates a personal account of his own suffering, narratives of the agony and fear that other headache sufferers endure, and meticulous reporting on headache-related research in science and medicine. Zeller has faced cluster headache episodes for over 30 years, starting when he was in his 20s.

“In some aspects, I suppose I was writing the book my entire adult life without realizing it,” Zeller observes. Indeed, he had amassed research material regarding these conditions for years while wrestling with his own headache challenges.

A central theme in the book is why society has not regarded cluster headache and migraine issues with greater seriousness — and, correlatively, why the science surrounding headache disorders has not progressed further. Although to be fair, as Zeller remarks, “Anything involving the brain or central nervous system is remarkably challenging to research.”

More broadly, Zeller proposes in the book that we have conflated everyday headaches — the kind that may arise from excessive screen time — with the far more severe and distinctly different disorders such as cluster headaches and migraines. (Some patients refer to cluster headaches and migraines in the singular, not plural, to stress that this is a continuous condition, not just repeating headaches.)

“Headaches are bothersome, and we endure them,” Zeller remarks. “But we use the identical term to describe these other conditions,” specifically, cluster headaches and migraines. This has likely reinforced our general disregard for severe headache disorders as urgent and distinct medical issues. Instead, we often perceive headache disorders, even critical ones, as something individuals should merely bear.

“There’s a certain implication of exaggeration we still associate with migraines or [other] headache disorders, and I’m uncertain that will change,” Zeller reflects.

Additionally, around three-quarters of individuals experiencing migraines are women, which has likely led the condition to “receive little attention historically,” as Zeller articulates. Or at least, in more recent times: As Zeller details in the book, an awareness of severe headache disorders dates back to ancient eras, and it’s plausible that they have garnered less attention in modernity.

A new shift in medical perspective

Nonetheless, for much of the 20th century, traditional medical beliefs held that migraines and cluster headaches arose from alterations or irregularities in blood vessels. However, in recent decades, as Zeller outlines, there has been a significant shift: These conditions are now recognized as being more neurologically based.

A pivotal breakthrough was the discovery in the 1980s of a neurotransmitter known as calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP. As researchers have uncovered, CGRP is released from nerve endings surrounding blood vessels and contributes to the manifestation of migraine symptoms. This introduced a new approach — and target — for combating severe head pain. The first medications to inhibit CGRP’s effects entered the market in 2018, and most researchers in this field now regard idiopathic headaches as neurological disorders, not vascular issues.

“That’s how science operates,” Zeller states. “Changing direction is difficult. It’s akin to maneuvering a ship on a dime. The same principle applies to the study of headaches.”

Many treatments aimed at obstructing these neurotransmitters have since been produced, yet only about 20 percent of patients appear to find enduring relief. As Zeller recounts, other patients experience benefits for approximately a year before the effects of a treatment diminish; many of these individuals now experiment with complex combinations of medications.

Severe headache disorders also appear to correlate with hormonal changes in individuals, who often begin to notice these ailments during their teenage years, with symptoms often lessening later in life. Thus, while headache medicine has achieved a recent advancement, considerably more work remains to be done.

Fostering a conversation

Amid all this, one set of inquiries persistently occupying Zeller’s thoughts is evolutionary: Why do humans suffer from headache disorders at all? There is no definitive proof that other species experience severe headaches — or that the incidence of major headache conditions in society has ever declined.

One theory, Zeller notes, is that “possessing a finely attuned nervous system could have been advantageous in our earlier stages.” Such a system might have aided our survival in the past, yet at the expense of causing intense disorders in certain individuals when the system malfunctions. We may uncover more about this as neurological headache research progresses.

“The Headache” has garnered extensive acclaim. Writing in The New Yorker, Jerome Groopman praised the “rich content in the book,” observing that it “intertwines history, biology, a review of contemporary research, accounts from patients, and a profound depiction of Zeller’s own struggles.”

For his part, Zeller expresses gratitude for the attention “The Headache” has received as one of the most recognized nonfiction titles published this summer.

“It has initiated a space for a type of dialogue that rarely emerges into the public eye,” Zeller observes. “I’m hearing from numerous patients who are simply saying, ‘Thank you for composing this.’ And that’s immensely gratifying. I’m most pleased to hear from individuals who believe it’s providing them a voice. I’m also receiving considerable feedback from doctors and researchers. The moment has created an opening for this conversation, and I’m thankful for that.”

“`