The initial occasion Steve Jobs showcased a public demonstration of the Apple Macintosh, in early 1984, included scripted humor as part of the launch. First, Jobs extracted the device from a bag. Then, utilizing voice technology from Samsung, the Macintosh delivered a witty remark about competitor IBM’s mainframes: “Never trust a computer you can’t lift.”

There’s a reason Jobs engaged in this. For the initial few decades that computing integrated into popular culture, beginning in the 1950s, computers appeared unfriendly, severe, and likely to oppose human interests. Consider the 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey,” where the onboard AI, HAL, turns against the astronauts. It stands as a notable cultural reference. Jobs, while promoting the idea of personal computing, employed humor to alleviate fears surrounding the devices.

“In contrast to the perception of computing as frigid and number-focused, the fact that this computer was employing voice technology to tell jokes made it seem less intimidating, less malevolent,” remarks MIT scholar Benjamin Mangrum.

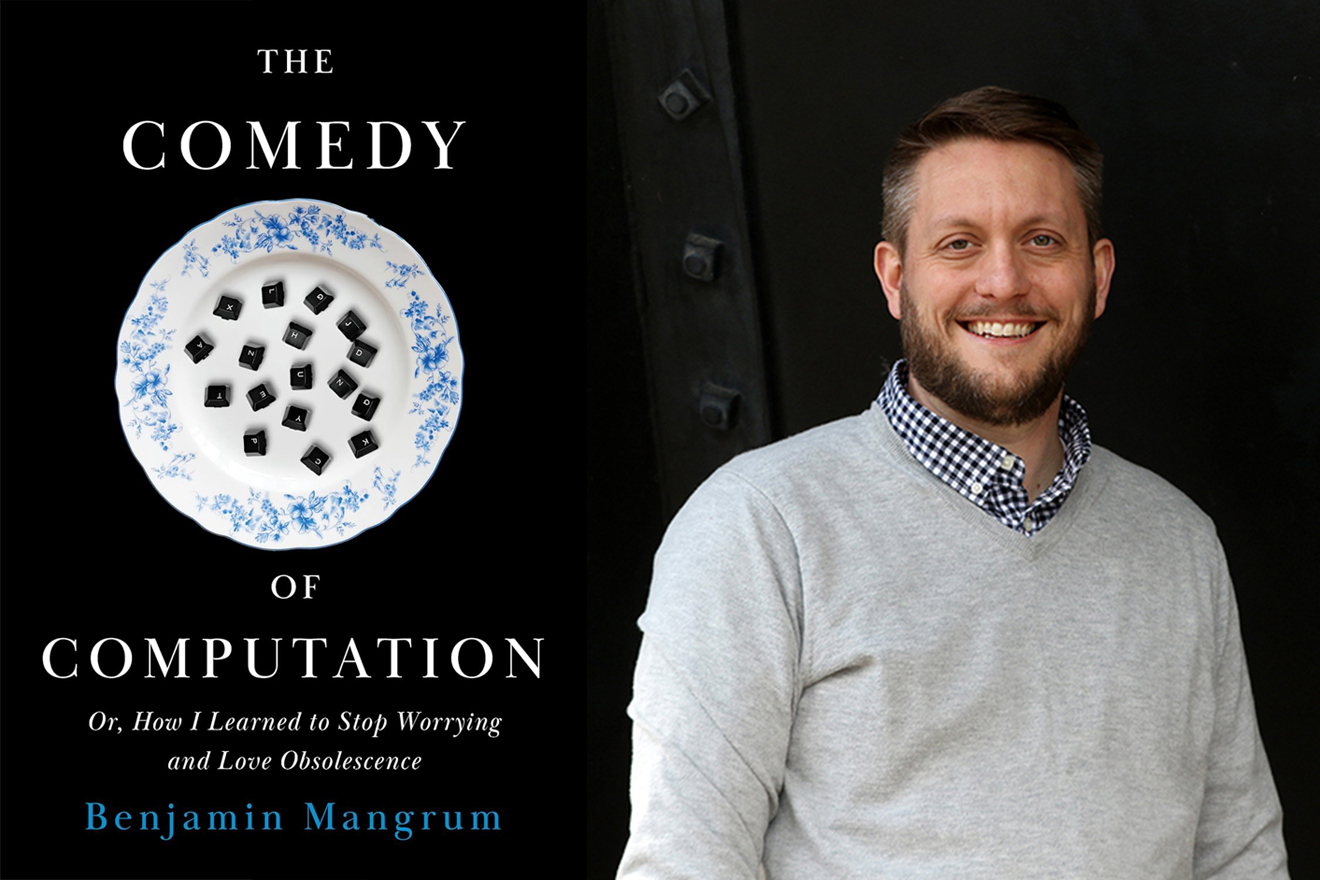

Indeed, this pattern appears throughout contemporary culture, in films, television, literature, and theater. We often confront our misgivings and anxieties about computing through humor, whether reconciling our relationship with machines or critiquing them. Now, Mangrum delves into this trend in a new publication, “The Comedy of Computation: Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Obsolescence,” released this month by Stanford University Press.

“Comedy has served as a means of making this technology feel commonplace,” states Mangrum, an associate professor in MIT’s literature program. “In scenarios where computing might seem impersonal or devoid of humanity, comedy enables us to weave it into our lives in a way that renders it understandable.”

Reversals of fortune

Mangrum’s fascination with the topic was partly ignited by William Marchant’s 1955 play, “The Desk Set” — a romantic comedy later adapted into a film featuring Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy — which explores, among other themes, how office personnel will coexist with computers.

Perhaps contrary to expectations, romantic comedies have emerged as one of the most significant modern cultural forms that wrestle with technology and its implications on us. Mangrum elaborates in the book: Their narrative structure frequently involves reversals, which can also extend to technology. Computing might initially appear daunting, but it can also unite individuals.

“A recurring theme in romantic comedies is that there are characters or circumstances in the storyline that hinder the joyful union of two individuals,” Mangrum observes. “Often, over the course of the narrative, the obstructive element or character transforms into an ally or collaborator, ultimately merging within the happy couple’s relationship. This provides a template for how certain cultural creators wish to depict the experience of computing. It starts as an obstacle and concludes as a partner.”

This narrative structure, Mangrum points out, traces back to ancient times and was prevalent in Shakespearean literature. Still, as he notes in the book, there is “no eternal essence called Comedy,” as its mediums and forms evolve over time. Beyond that, specific jokes about computing can swiftly become outdated. Steve Jobs ribbed mainframes, and the 1998 Nora Ephron comedy “You’ve Got Mail” elicited laughs from dial-up modems, yet those jokes may leave most people bewildered today.

“Comedy is not a static resource,” Mangrum states. “It’s an ever-evolving toolkit.”

Advancing this transformation into the 21st century, Mangrum notes that much of computational humor revolves around a category of commentary he dubs “the Great Tech-Industrial Joke.” This centers on the disparity between the noble-sounding stated ambitions of technology and the occasionally dismal results it yields.

Social media, for instance, promised new realms of connection and social discovery, and it does offer benefits people appreciate — but it has also fostered polarization, misinformation, and toxicity. The social consequences of technology are multifaceted. Entire television series, such as “Silicon Valley,” have explored this landscape.

“The tech industry asserts that some of its innovations have groundbreaking or utopian objectives, but many of their accomplishments fall significantly short,” Mangrum remarks. “It sets the stage for humor. Individuals claim we’re saving the planet, while in reality, we’re merely processing emails faster. But it serves as a form of critique aimed at big tech, given the complexity of its products.”

A complicated, messy picture

“The Comedy of Computation” examines various other dimensions of modern culture and technology. The concept of personal authenticity, as Mangrum notes, is a relatively recent societal construct — and it’s another realm of life that collides with computing, as social media is rife with accusations of inauthenticity.

“That ethics of authenticity relates to comedy, as we joke about individuals lacking authenticity,” Mangrum states.

“The Comedy of Computation” has garnered acclaim from other academics. Mark Goble, an English professor at the University of California at Berkeley, has labeled it “essential for understanding the technological landscape in its complexity, absurdity, and vibrancy.”

For his part, Mangrum underscores that his book is an inquiry into the overall complexity of technology, culture, and society.

“There’s this incredibly intricate, messy panorama,” Mangrum explains. “And comedy occasionally discovers a means of experiencing and deriving enjoyment from that messiness, while other times, it neatly packages it with a moral that can oversimplify.”

Mangrum emphasizes that the book focuses on “the blend of threat and enjoyment that’s inherent throughout the history of computing, in the ways it has been integrated and shaped society, featuring genuine advancements and benefits, alongside legitimate threats, such as those posed to employment. I’m intrigued by the duality, the simultaneous and seemingly conflicting aspects of that experience.”