“`html

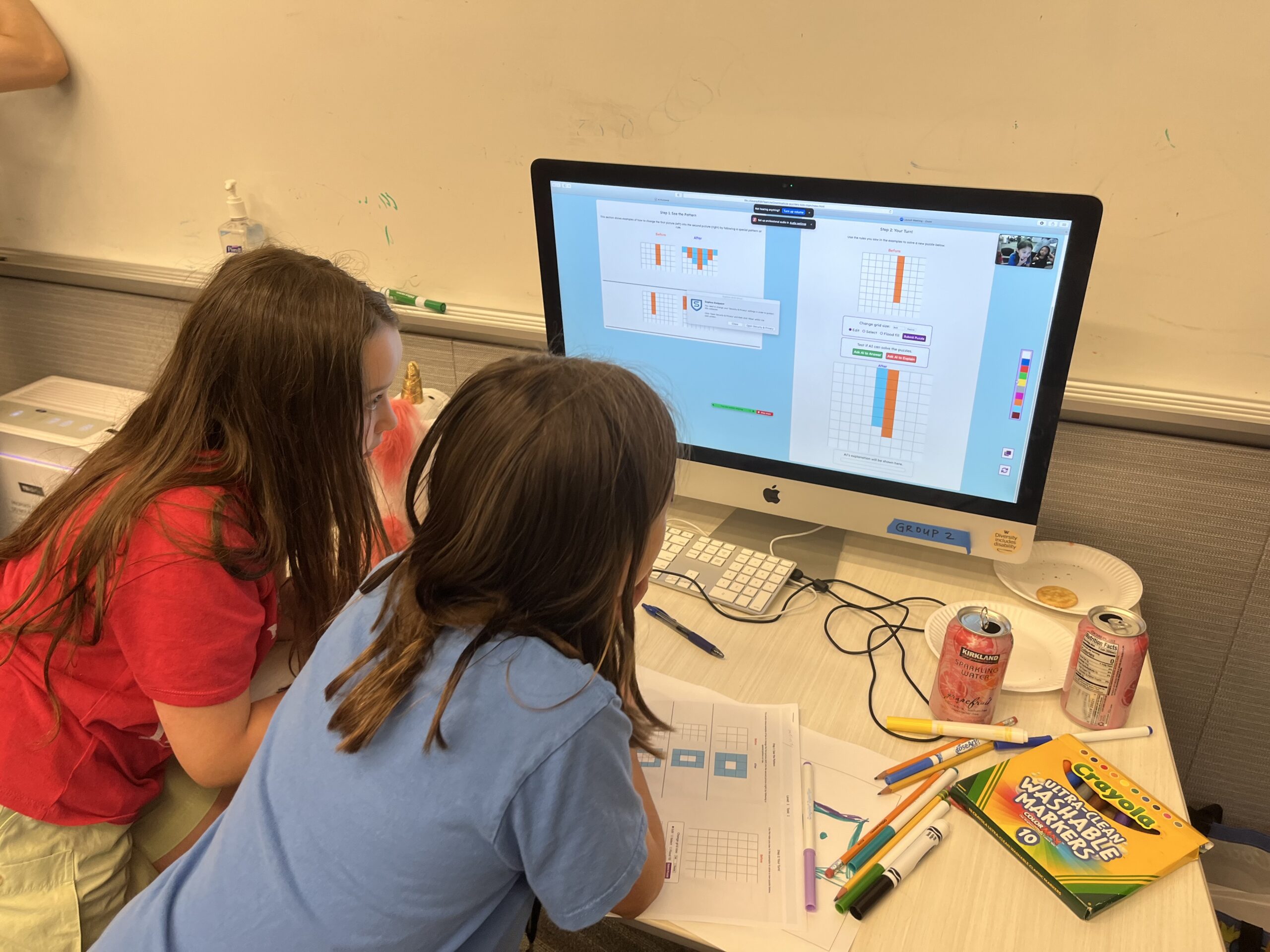

Researchers from the University of Washington created the game AI Puzzlers to illustrate an area where AI systems continue to commonly and conspicuously struggle: resolving specific reasoning puzzles. In the game, players have the opportunity to tackle puzzles by finishing patterns of colored blocks. They can then prompt various AI chatbots to resolve the puzzles and request explanations for their answers — which they almost always fail to provide accurately. Here, two youngsters from the UW KidsTeam group experiment with the game.University of Washington

Although the present generation of artificial intelligence chatbots often miss basic information, the systems respond with such assurance that they’re frequently more convincing than humans.

Adults, even those like lawyers with extensive expertise, often fall victim to this. Nonetheless, detecting mistakes in text is particularly challenging for children, as they frequently lack the contextual knowledge to identify inaccuracies.

University of Washington researchers designed AI Puzzlers to illustrate an area where AI systems still typically and overtly fail: solving particular reasoning puzzles. Players engage with ‘ARC’ puzzles (short for Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus) by completing patterns of colored blocks. They can then solicit various AI chatbots to attempt solving the puzzles and have the systems clarify their responses — which they almost invariably misjudge. The team evaluated the game with two groups of children. They discovered that the kids improved their critical thinking regarding AI responses and learned techniques to steer the systems towards more accurate answers.

Researchers shared their results on June 25 at the Interaction Design and Children 2025 conference held in Reykjavik, Iceland.

“Children naturally enjoyed ARC puzzles and they’re not confined to any language or culture,” said the lead author Aayushi Dangol, a doctoral student at UW focusing on human-centered design and engineering. “Because the puzzles are solely based on visual pattern recognition, even children who are not yet readers can participate and learn. They experience great satisfaction in successfully resolving the puzzles, particularly when they see AI — which they might view as highly intelligent — struggle with puzzles they perceived as simple.”

ARC puzzles were created in 2019 to pose challenges for computers but be straightforward for humans, as they require abstraction: the ability to observe a few instances of a pattern and then apply it to a new scenario. Current state-of-the-art AI models have made strides with ARC puzzles, yet they have not matched human capability.

Researchers constructed AI Puzzlers with 12 ARC puzzles that children can solve. They can then compare their answers with those from various AI chatbots, selecting the model from a dropdown menu. An “Ask AI to Explain” button generates a textual explanation of its solution attempt. Even if the system solves the puzzle correctly, its explanation of how it achieved that is often imprecise. An “Assist Mode” allows children to help guide the AI system to a correct answer.

“At first, children were offering quite broad suggestions,” Dangol noted. “For instance, ‘Oh, this pattern resembles a doughnut.’ An AI model might not grasp that a child means there’s a hole in the center, so the child would need to reiterate. They might say, ‘A white space surrounded by blue squares.’”

The researchers assessed the system during the UW College of Engineering’s Discovery Days last year, engaging over 100 children from grades 3 to 8. They also conducted two sessions with KidsTeam UW, a project collaborating with children to design technology collectively. In these sessions, 21 children aged 6-11 played AI Puzzlers and collaborated with the researchers.

“The KidsTeam participants are accustomed to providing suggestions on how to improve technology,” said co-senior author Jason Yip, a UW associate professor at the Information School and the KidsTeam director. “We hadn’t truly considered incorporating the Assist Mode feature, but during these co-design sessions, discussions with the children on how to support AI in solving the puzzles prompted that idea.”

Throughout the evaluations, the team discovered that children could identify errors both in puzzle solutions and in the text explanations provided by AI models. They also recognized differences in the thought processes of human brains compared to how AI generates information. “This is the internet’s mind,” one child remarked. “It’s trying to solve it based only on the internet, but the human brain is inventive.”

The researchers also determined that as children utilized Assist Mode, they learned to view AI as a tool that requires direction rather than merely as a source of answers.

“Kids are intelligent and capable,” stated co-senior author Julie Kientz, a UW professor and chair in human-centered design and engineering. “We should provide them with opportunities to form their own perspectives on what AI is and what it isn’t, as they are truly adept at recognizing it. And they can be more skeptical than adults.”

Runhua Zhao and Robert Wolfe, both doctoral students in the Information School, as well as Trushaa Ramanan, a master’s student in human-centered design and engineering, are also co-authors of this paper. This research received funding from The National Science Foundation, the Institute of Education Sciences, and the Jacobs Foundation’s CERES Network.

For additional details, reach out to Dangol at [email protected], Yip at [email protected], and Kientz at [email protected].

“`