“`html

Throughout all campuses of Washington University in St. Louis, numerous scholars possess a passion to comprehend the natural forces that mold our climate, well-being, culture, and physical environment. A significant number also hold a dedication to educating — and partnering with — the upcoming generation of environmental researchers.

“We have 117 faculty and research personnel affiliated with the Center for the Environment, and the majority of them supervise PhD students and other graduate scholars,” states Daniel Giammar, director of the Center for the Environment and the Walter E. Browne Professor of Environmental Engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering. Giammar, who personally mentors five graduate scholars, notes that the contributions of students can occasionally be overlooked outside their specific labs and departments.

“Graduate scholars are the driving force behind the university’s research,” he asserts. “They exert immense effort, possess remarkable creativity, and none of our publications, particularly in my field, would be feasible without them.”

The Center for the Environment serves as an interdisciplinary nexus, offering programming that fosters discussions between graduate scholars and faculty. Every few months, the center also arranges a lunch and an opportunity for graduate scholars to convene to deliberate on a project or manuscript. “I believe that’s where we’ve really added considerable value, by fostering that community across various disciplines,” Giammar remarks. Graduate scholars further mentor undergraduates in an intensive summer research initiative offered by the center.

This spring, at the 2025 Environmental Research Symposium, some of the nearly 500 WashU graduate scholars engaged in environmental issues exhibited posters regarding their current endeavors. Subjects included: reducing the carbon emissions of MRI scanners; assessing ventilation systems in commercial kitchens; endangered bat habitats in Indiana; the effects of urban development on St. Louis-area wildlife; the history of WashU’s Tyson Research Center; the relationship between light exposure and colorectal cancer risk; and the impact of humidity on tiger mosquito survival.

A smaller contingent delivered public lightning talks regarding their investigations. Read on for a selection of highlights from the presentations.

Assisting endangered species in navigating mosaic landscapes

Globally, rapid deforestation endangers biodiversity. To grasp the magnitude of the issue and identify where interventions are crucial, scientists require detailed imagery of the environments where animals are at risk.

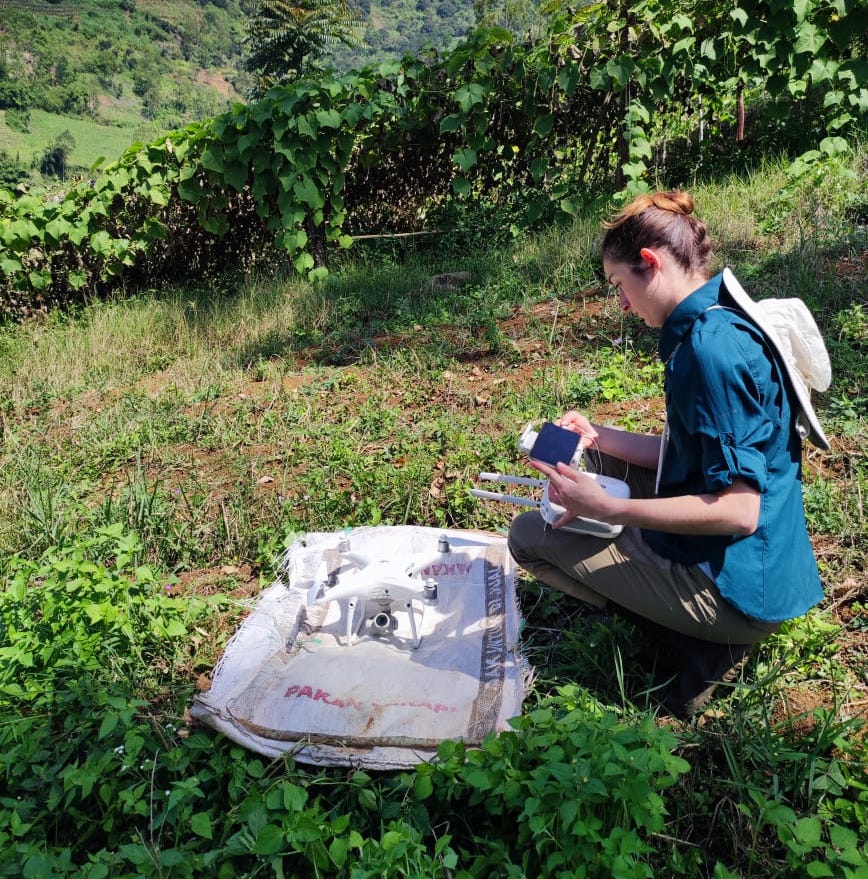

“Satellite imagery is frequently utilized to monitor wildlife habitats,” explains Leslie Annette Paige, a graduate scholar in biological anthropology in Arts & Sciences, “but even very high-resolution satellite images can struggle when working in mosaic landscapes that vary on minuscule scales.” To counter this challenge, Paige employs drones and other remote-sensing technologies to provide enhanced clarity.

Rather than dense forests or open fields, mosaic landscapes take shape as a patchwork of trees, crops, and other flora. This is evident in specific agricultural regions on the island of Java, home to the critically endangered Javan slow loris. This primate moves through trees using grasping hands; it cannot walk on the ground. However, it can navigate across a vining crop known as labu, which grows on trellises.

“With my drone imagery over the habitat of the Javan slow loris, we are able to differentiate various crop types present in the landscape,” Paige states. Utilizing these detailed images, conservationists installed canopy bridges in targeted areas where the lorises required additional pathways to traverse. The bridges also incorporated irrigation devices beneficial to local farmers. Paige is conducting similar work in Madagascar with lemur populations.

The movement of rare earth elements

“It’s hard to envision our lives without hard drives, data communication technologies, MRI machines, or hybrid vehicles. And all these applications share a commonality. They contain rare earth elements, or REEs,” shares Elmira Ramazanova, a graduate scholar in energy, environmental, and chemical engineering at McKelvey Engineering.

Ion-adsorption deposits represent a key source of rare earth elements, Ramazanova elaborates. “When it comes to heavy REEs, they essentially dominate the entire global market.” The clay-rich deposits form as minerals containing REEs weather and disintegrate. Aqueous REEs then adhere to the surfaces of clay minerals like kaolinite. Collaborating with Giammar, Ramazanova undertook a study to deepen the understanding of the chemistry occurring at these deposit sites.

“We are seeking to comprehend how these REEs adhere. Can we model this absorption?” she inquires.

In her research, Ramazanova conducted experiments with kaolinite and various REEs. She created a model that successfully predicted adsorption across a broad range of water chemistry conditions. The model illustrates how adsorption varies with different pH levels, fluctuating concentrations of electrolytes, and other variables.

Currently, most active ion adsorption deposits are located in southern China. As new sites globally endeavor to develop their own sources of REEs, Ramazanova’s model could assist in predicting the efficiency of REE extraction. Her study was recently published in ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, a prominent environmental chemistry journal.

Conserving nature

Shivani Shenoy, a first-year MFA student in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, is an illustrator interested in environmentalism and visual culture. “I have been intrigued to discover how illustrated books have fostered ecological awareness over the years for various audiences,” she states.

Shenoy brought this inquisitiveness to University Archives, where she discovered a long tradition of illustrated works pertaining to the natural world, ranging from natural history texts to children’s tales and personal reflections on nature.

“Thomas Bewick’s A History of British Birds from 1797 was renowned for his pioneering white line engraving, but also for being tailored for general audiences, rendering bird science accessible to ordinary people,” Shenoy notes. She also pointed out 19th-century botanical illustrations created for gardeners.

“These books communicate at the juncture of art and science, promoting observation of non-human life surrounding us,” Shenoy observes. Children’s picture books also boast a long history of nurturing appreciation and curiosity about nature.

In more recent years, Shenoy discovered that authors and artists have created visual publications to document and reflect upon environmental issues. For instance, The Realm of Nature Mine by J.G. Lubbock offers firsthand personal insights into daily interactions with nature and observations of climate change, she highlights.

As a nature illustrator, Shenoy’s exploration of the archives informs her creative process. It also provides insights into how books can engage with diverse audiences and contribute to conservation initiatives.

“Science alone cannot address climate change, nor can design or illustration, but through collaborations and scholarly exchanges between various disciplines, we can aim to enhance environmental awareness, appreciation, and vocabularies,” Shenoy asserts. “Especially in our current times — what better medium than books?”

The post Environmental futures appeared first on The Source.

“`