“`html

Their titles resemble something from a graphic novel: the speckled lanternfly, the yellow-legged wasp, the Joro arachnid. However, for researchers and agriculturalists, invasive insects are not just fantasy—they represent a genuine and escalating danger.

Though you might perceive them merely as a glimmer in the foliage or a crunch underfoot, a 2021 analysis projected that invasive insects could impose costs exceeding $27 billion annually on North America. Academics at the University of Georgia are dedicated to identifying which invasive insects are merely harmless oddities and which are potential catastrophe creators capable of destabilizing ecosystems and damaging crops.

What Constitutes an Invasive Species?

Not all foreign insects qualify as invasive. Some, such as banana spiders or the seven-spot ladybug, have existed long enough to be confused with indigenous species. Instead, they have seamlessly integrated into the ecosystem without causing significant disruption. These “non-native” or “exotic species” are categorized as insects introduced to habitats where they do not naturally exist.

For a species to be deemed invasive, it must be non-native and inflict damage. Will Hudson, a professor and Extension specialist at the University of Georgia, mentions that numerous insects generating excitement are so recent that their environmental or economic impacts remain uncertain.

“Consider the Joro Spider as an example,” states Hudson. “They’ve surged in numbers here, but they are on the verge of being classified as invasive. We haven’t identified any significant adverse effects from Joros on the environment or other native insects. Nevertheless, due to the inconvenience caused by their webs and sheer population, we regard them as invasive.”

The speckled lanternfly is another relatively recent invasive species that is causing alarm. A striking black, white, and red insect from Asia, the speckled lanternfly was first observed in the woodlands of Pennsylvania but has since expanded to over a third of the nation.

“My daughter lives in New York, and she sent me photos of structures where entire sides were blanketed with these bugs,” Hudson adds.

Unlike the Joro Spider, the speckled lanternfly is anticipated to cause considerable economic and environmental harm. Who are its victims? You might want to stockpile wine while it’s still available.

Invasive Insects and Agriculture

Among the speckled lanternfly’s preferred food sources is the sap from grapevines. In regions where the insect has already taken hold, the estimated worth of grape and tree fruit sectors is $915 million.

“Despite their small size, their potential to disrupt the grape industry is enormous,” notes Hudson. “Wine grapes. Table grapes. Muscadines. They’ll feast on all of those. And if they taint grapes intended for wine, the flavor of that wine could be spoiled.”

The brown marmorated stink bug serves as another instance of non-native pests wreaking havoc on agriculture. It arrived from East Asia in the early 1900s and inflicted significant damage on apple orchards and vineyards in the Mid-Atlantic. Fortunately, as it migrated south, its impact diminished, partly due to the region’s warmer, more humid climate and a wealth of native stink bug species that lessened its influence.

“Insect development relies on temperature,” explains Hudson. “So while warmer climates can hasten their life cycle, if they aren’t well suited to our conditions, they may struggle to thrive.”

Yet, with insects adapting rapidly and spreading quietly, experts emphasize the crucial nature of early detection and swift action to protect the future of American agriculture. One of the most essential elements in managing these invasions is preventing them from arriving in the first place.

How Do Invasive Species Spread?

Invasive insects don’t require wings to traverse states or even continents. They have discovered an efficient means to journey across the country with minimal effort: humans. Insects like the speckled lanternfly can cling to or deposit their eggs on ships, automobiles, trains, planes, and any other objects that travel long distances.

“If you transport your RV from New Jersey to Florida for the winter, you never know what might have hitched a ride,” Hudson points out. “They’re more than willing to lay their eggs on the side of your vehicle, camper, or virtually any other mode of transport. So without your awareness, you’re aiding their dissemination.”

Global trade is one of the primary factors responsible for allowing invasive insects to infiltrate new areas. Yellow-legged hornets take advantage of their lengthy hibernation periods when new queens enter a crack or crevice somewhere in a shipping container to spend the winter. They typically don’t emerge until the following spring and establish a new colony wherever they awaken.

“If you’re discussing a boat,” Hudson clarifies, “it’s almost always the eggs that are transported. They’re resilient enough to endure the journey.”

Once an invasive species arrives, returning it or eradicating it completely is nearly impossible. So, what should you do?

What Actions Should You Take Regarding Invasive Insects?

You don’t require a degree in entomology to safeguard your community against invasive insects. All you need are your eyes, your smartphone, and a bit of curiosity. According to Chuck Bargeron, director of the University of Georgia’s Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health, the public often serves as the initial line of defense in recognizing new threats.

“If you encounter something that appears unusual, ensure you inform someone about it,” advises Bargeron. “Because that’s how we can address the next issue early on—and take action before it becomes much more challenging and significantly more costly to counter.”

Over the last two decades, Bargeron’s team has created applications and websites—such as the widely utilized EDDMapS (Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System)—to streamline the reporting process. These platforms allow average individuals to educate themselves about invasive species and report sightings in real time. Users can simply snap a picture and upload it, prompting experts to verify and respond.

“The public is already out there enjoying state parks, campgrounds, and their backyards,” Bargeron states. “This makes you our most effective first detectors. There have been numerous instances where a new species was reported in this manner.”

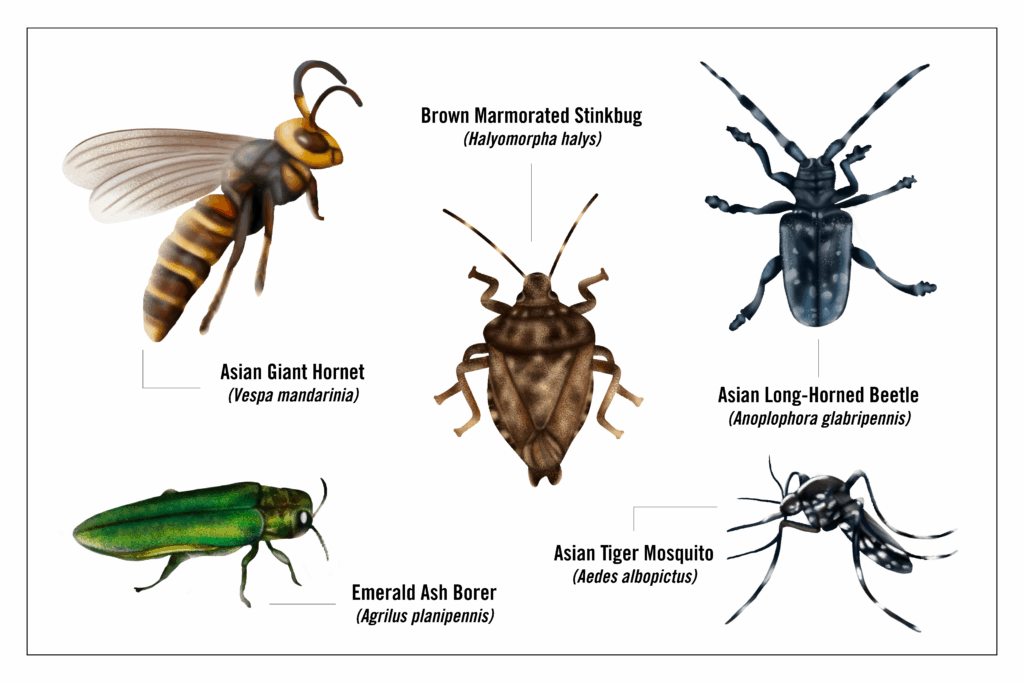

You may not even realize that some of the insects buzzing around your meal or pollinating your garden belong to an invasive species. There are numerous different ones in the United States, including the:

- Brown Marmorated Stinkbug

- Asian long-horned beetle

- Emerald ash borer

- Asian giant hornet

- Asian tiger mosquito

If you observe something peculiar—whether it’s an exceptionally large hornet, a beetle with zebra-patterned antennae, or a web unlike anything you’ve encountered before—don’t disregard it. Reach out to your local county extension agent or forestry commission or use one of the mobile tools to report it.

The post Invasive Insects in the US: Are Invasive Species a Problem? appeared first on UGA Today.

“`