The realm of Aksum was among the most formidable empires globally during the fourth century. It significantly influenced the chronicles of Egypt, Persia, and Rome, alongside the nascent phases of Christianity and Islam. However, Aksum’s achievements have often been disregarded due to their documentation in the ancient African dialect of Ge’ez.

Click to view the complete transcript of the episode

Ways of Knowing

The World According to Sound

Season 2, Episode 3

Ge’ez

[instrumental music plays]

Sam Harnett: In the center of the fourth century CE, the realm of Aksum was among the most potent empires around the globe. Located in what is now Ethiopia and Eritrea, it extended from Sudan across the Red Sea to Yemen. Its position on the Red Sea enabled it to dominate the trade route between Rome and India. It significantly aided the narratives of Egypt, Persia, and Rome, along with the early stages of Christianity and Islam. Aksum documented a comprehensive written account of its triumphs, yet this record was frequently neglected by Classics scholars, partly because of its composition in the ancient African language of Ge’ez.

[background music continues]

[Hamza Zafer reading Ge’ez]

SH: Similar to Latin, Ge’ez is seldom spoken in contemporary times. It continues as the liturgical language within the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Churches. However, during the fourth century, it served as the language of the Aksum empire.

[Zafer reading Aksum inscription in Ge’ez]

SH: This inscription details how Aksum triumphed over its rivals and expanded its territories. It is being recited in Ge’ez by Hamza Zafer, an educator of Middle Eastern languages and cultures.

[Zafer continues reading in Ge’ez]

SH: The inscription was engraved onto a massive stone slab at the heart of Aksum. It’s one among numerous stone slabs, or stellae, that Aksum kings raised during the empire’s zenith. Over a hundred remain standing in contemporary Aksum in Northern Ethiopia. These stones bore the kingdom’s achievements inscribed not just in Ge’ez, but also in Ancient Greek and Sabiac. Much like the Rosetta Stone that assisted in deciphering Egyptian Hieroglyphics, these other languages offered insights into Ge’ez.

[Zafer continues reading in Ge’ez]

Hamza Zafer: This inscription primarily celebrates a specific conquest. Most inscriptions from this period tend to share that focus.

SH: For Professor Zafer, the Aksumite Empire is merely one of many historical and cultural threads that this language evokes.

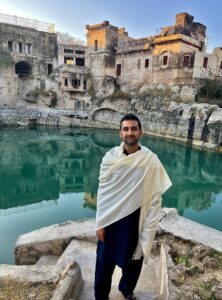

HZ: I have been instructing in Ge’ez for several years. I’m not from Ethiopia or Eritrea. My origins are in Pakistan. Yet, I was captivated by the language for various reasons, one being my aspiration to introduce the languages of the Global South—classical languages of the Global South—which also encompasses languages from regions like Pakistan.

SH: Hamza’s passion for Ge’ez ignited from his quest to better comprehend the Quran. He sought to explore how diverse cultures and languages shaped the writing of this sixth-century text and how that writing depicted the world that crafted it.

HZ: The language of the Quran showcases significant Syriac, Aramaic, Hebrew, and even Greek influences. It’s a text from the sixth century in Western Arabia, reflecting a blend of various cultures. However, one language that was integral to the Quran’s composition, which I found challenging to access during my doctoral studies, was Ge’ez, classical Ethiopic. That’s where my fascination began—driven by curiosity to gain a broader perspective on how the language of the Quran mirrors its cultural backdrop.

SH: The Quran contains a plethora of vocabulary derived from Ge’ez. Mastery of this language enriches one’s understanding of the text—its history, and cultural context.

[instrumental background music plays]

Hamza’s exploration of Ge’ez led him to an array of captivating texts: the Aksumite inscriptions, early adaptations of biblical narratives, letters regarding the advent of Islam, poetry, historical records, and religious documents. He became utterly entranced by the language itself—its phonetics and elegance. Soon, his focus sharpened specifically on studying Ge’ez.

HZ: The rationale is akin to studying Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, or Arabic. It offers invaluable insights into the past, into the premodern era.

SH: Through Ge’ez, the perspective on world history emerges quite distinct from that seen through other classical languages like Latin and Greek. It presents an alternative narrative to a Eurocentric interpretation of history.

HZ: Engaging with a language like Ge’ez fundamentally reshapes your understanding of the historical narrative. Much of our historical comprehension, undoubtedly, stems from a colonial and postcolonial viewpoint that places Europe at the forefront. However, delving into a language like Ge’ez opens doorways to another realm, unveiling alternative avenues of knowledge. It can represent an intellectual as well as a political move. We’re still in the early phases of Ge’ez studies. I envision that 20, 30, or even 50 years down the line, it might not seem so peculiar to pursue a language like Ge’ez. Right now, however, as we remain entrenched in an era viewing knowledge as originating from Europe and the North, it appears to be an anomaly. But that is a misconception. It is a language with a 2000-year legacy.

SH: Within the majority of Classics departments, Greek and Latin remain the sole languages studied.

HZ: Numerous other languages akin to Ge’ez belong to what we now define as the Global South; these possess classical traditions. Studies of these languages reveal alternative pathways of thought; they uncover different hierarchies of knowledge that could exist. Hence, one of the fascinations in studying Ge’ez is that it broadens your understanding of diverse connections. You come to realize that Africa and India, Africa and Arabia, Africa and Europe engaged in various forms of exchanges and movements of ideas. Africa hosted cultural producers and intellectual traditions whose ideas soared across boundaries, and this was the medium through which they spread.

SH: Until recently, European and American scholars primarily studied Ge’ez due to its significance in Christian history. The Aksum Empire embraced Christianity shortly after Rome did in the fourth century, and Ge’ez became the language of Ethiopian Christianity. Some of the oldest preserved biblical texts are in Ge’ez.

HZ: This is the initial chapter of the Book of Jonah.

[Zafer reads the Book of Jonah in Ge’ez]

SH: The narrative bears similarity to the version preserved in Ancient Greek, though there are notable differences. For example, in the Ge’ez rendition, God is addressed in an entirely distinct manner. Rather than a name, he is referred to as “The Lord of the Land,” representing a much earlier nomenclature for a deity.

[Zafer continues reading the Book of Jonah in Ge’ez]

SH: Scholars have meticulously examined these variations to gain deeper insights into the early Christian storytelling. Yet, this has often marked the limit of Ge’ez scholarship.

HZ: The“`html

The present task is to place Ge’ez at the core of our inquiry, not merely in connection with the North or the Mediterranean realm, but to comprehend it for its intrinsic value as a literary body—a premodern literary body that links the Indian Ocean domain to the Eastern Mediterranean, while also having a localized context uniting Arabia and Africa.

SH: As with any ancient language, Ge’ez offers a distinct perspective, a unique approach to understanding the world. You don’t require a specific purpose or aim to gain significantly from studying it.

HZ: Learners are often discouraged from enrolling in courses that lack an immediate practical application. I believe that pursuing a classical language—whether European, African, or Asian—allows one to slightly bypass this pressure, engaging in a purely intellectual endeavor for the joy of exploring this alternate universe.

[background music begins]

HZ: For me, simply engaging with a classical language as an intellectual pursuit is immensely significant for developing critical awareness. It imparts a sense of historicity. Something that appears so steadfast and obvious, like a language—when delving into a premodern language with an extensive past such as Ge’ez—you realize that language evolves, and this understanding is crucial. Language transforms how people process thoughts. The manner in which individuals formulate concepts undergoes change. Furthermore, this does not serve an immediate practical function, yet it opens pathways—much like time travel—to an entirely different universe of culture, language, cognition, and belief.

CH: Here are five works that will enhance your comprehension of publishing culture and the digital humanities as modes of knowledge.

“The Throne of Adulis,” by Glen Bowersock

A vivid reimagining of the struggle between Christian Ethiopians and Jewish Arabs in the sixth century. This narrative has only been made possible now due to a marble throne at the Ethiopian port of Adulis, adorned with Ge’ez inscriptions.

“The Garima Gospels,” by Judith McKenzie

The oldest existing Ethiopian gospel texts embody the phonetic charm and artistry of Ge’ez. They also shed light on the history of the Aksumite kingdom and the early stages of Christianity.

“The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages,” by François-Xavier Fauvelle

An account of the Middle Ages focused on Africa, where the creations of artists and intellectuals in regions like Ghana, Nubia, and Zimbabwe resonated beyond the continent’s periphery.

“The Red Sea: In Search of Lost Space,” by Alexis Wick

A thorough, extensive history of the Red Sea that presents a deeper argument on how Eurocentrism has left us with a limited and skewed perception of the world.

“Decolonizing the Mind,” by Ngugi wa Thiong’o

This compilation of essays explores how language influences national culture, historical narratives, and identity; and outlines a vision for linguistic decolonization.

SH: Ways of Knowing is a production by The World According to Sound. This season explores various interpretive and analytical methodologies within the humanities. It was created in partnership with the University of Washington and its College of Arts & Sciences. Music is provided by Ketsa, Nuisance, and our colleagues, Matmos. The World According to Sound is produced by Chris Hoff and Sam Harnett.

END

Similar to Latin, Ge’ez is infrequently spoken these days. It is offered at merely three universities in the Western world, one of which is Hamza Zafer at the University of Washington. Zafer, an associate professor of Middle Eastern languages and cultures, was inspired to engage with Ge’ez by his ambition to promote classical languages of the Global South. In this episode, Zafer shares how centering Ge’ez revitalizes various aspects of history and culture.

This is the third installment of Season 2 of “Ways of Knowing,” a podcast that illustrates how the study of the humanities can resonate with daily life. Through a collaboration between The World According to Sound and the University of Washington, each episode highlights a faculty member from the UW College of Arts & Sciences, the work that inspires them, and recommended resources for further exploration of the topic.

“`