“`html

Campus & Community

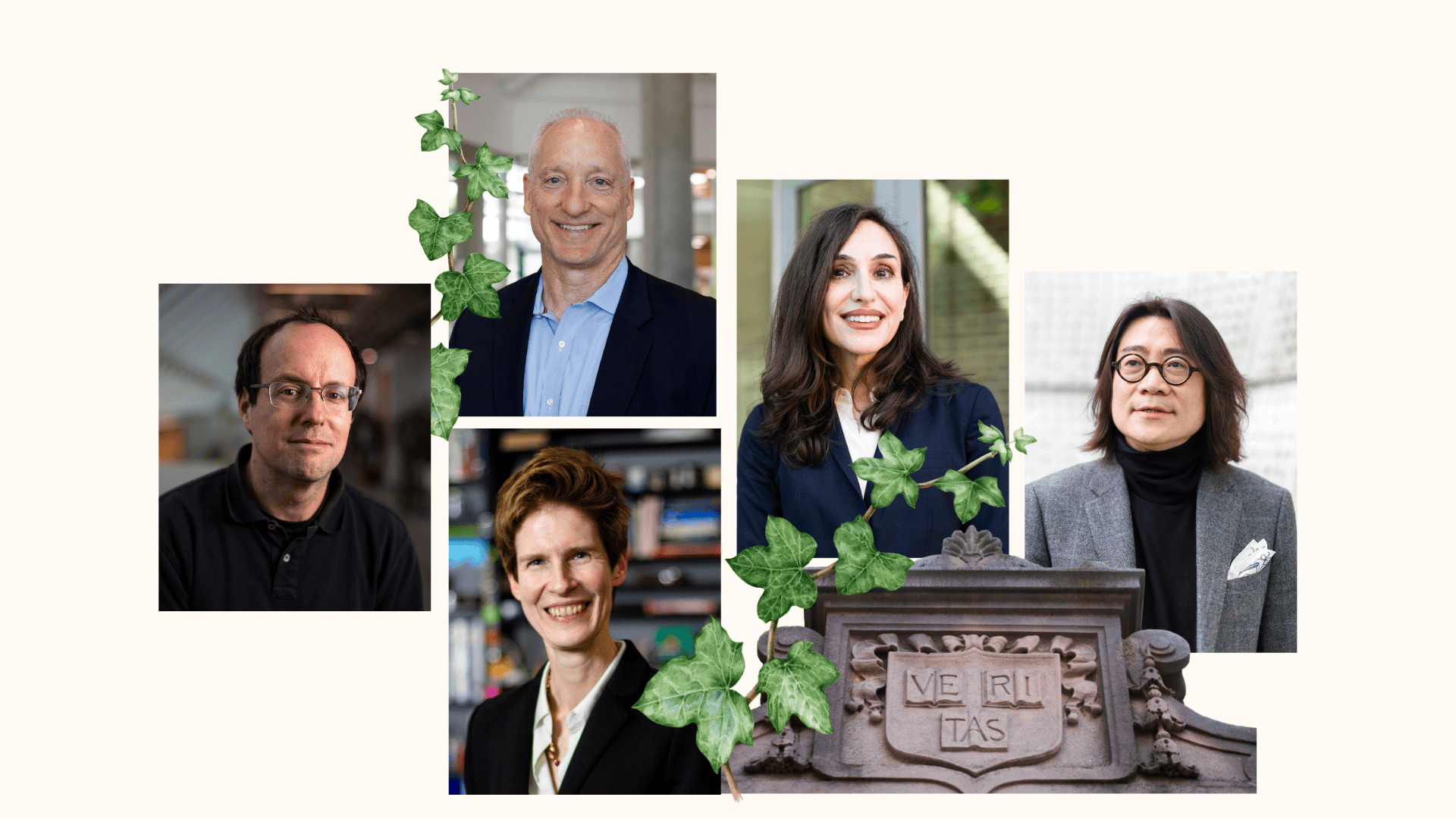

Five faculty members appointed as Harvard College Professors

Image credits: Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer, Grace DuVal, and Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer; photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Recognized for outstanding teaching across disciplines from geometry to politics

Five faculty members have been granted a Harvard College Professorship in recognition of their excellence in undergraduate education, spanning areas from high-dimensional geometry to comparative politics. Hopi Hoekstra, Edgerley Family Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, made the announcement of the honorees on May 6. They are:

- Denis Auroux, Herchel Smith Professor of Mathematics

- Christina Maranci, Mashtots Professor of Armenian Studies

- Michael Smith, John H. Finley Jr. Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences

- Karen Thornber, Harry Tuchman Levin Professor in Literature and Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations

- Yuhua Wang, Ford Foundation Professor of Modern China Studies

“I am thrilled to acknowledge these five exceptional colleagues for their roles in teaching, mentorship, and research,” Hoekstra stated. “Their enthusiasm, rigor, and inventiveness motivate our students daily, enabling them to pose significant questions, delve into new concepts, and evolve as thinkers and scholars. I am thankful for their remarkable dedication to our students and our educational purpose.”

The Harvard College Professorship was initiated in 1997, supported by a donation from John and Frances Loeb. Professors retain the title for a period of five years and receive assistance for a research fund, summer salary, or a semester of compensated leave.

Denis Auroux.

File photo by Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Revealing ‘deep connections’ within mathematics

Auroux is a pure mathematician who has dedicated his career to exploring ethereal fields like high-dimensional geometry, where certain shapes are too abstract to be represented on a blackboard. He derives much more concrete rewards from the act of teaching.

“I feel truly fulfilled when I can explain something to a student in a manner that makes it click for them,” Auroux shared. “Witnessing the acquisition of knowledge is something I cherish.”

Auroux has been part of Harvard since 2018. Trained in France, he has held previous positions at the Ecole Polytechnique, MIT, and Berkeley. One of his noteworthy classes is the prestigious “Math 55,” a fast-paced curriculum designed for advanced first-year students.

He characterizes his teaching approach as traditional — featuring lectures, a “significant quantity” of homework, and available office hours — and he continues to favor a conventional chalkboard. He aims to guide students towards a profound understanding of mathematics from various perspectives: algebra, geometry, and analysis. Throughout the academic year, the class revisits the very same concepts from different branches of the discipline.

“There are substantial connections that weave through different areas of mathematics,” he mentioned. “It’s exceedingly beautiful when you’re able to highlight that in a class.”

Auroux is also on a quest for those profound connections. He investigates the geometry of abstract spaces that are not encountered in daily life but are of significant interest to mathematicians and theoretical physicists. His research areas encompass symplectic geometry, low-dimensional topology, and mirror symmetry.

“I continue to grapple with the questions I sought to understand a decade ago,” Auroux remarked. “My definition of understanding is evolving. While I’ve grasped certain concepts, I’ve come to realize there’s far more I have yet to comprehend. Perhaps mathematicians tend to be slightly obsessive about this.”

Christina Maranci.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Prioritizing visuals to stimulate curiosity

Maranci, an art historian specialized in pre-modern Armenia, prefers to commence her lectures with images — perhaps a 7th-century Armenian manuscript illustrating the Annunciation, or photographs from her fieldwork in Eastern Turkey — encouraging her students to initially engage with the image before delving into its understanding.

“One of the marvelous aspects of working with art and visual culture is that you can present them with items they are unfamiliar with, and they simply observe,” Maranci explained. “Then you guide them to question what they are examining. For me, it’s a tremendously effective method of teaching and it also encourages curiosity.”

Maranci’s expertise lies at the intersection of art, architecture, and material culture of medieval Armenia. She delivers courses covering all facets of Armenian culture and history, from liturgical textiles to art and literature.

In Maranci’s view, teaching is an immersive experience. She refrains from relying on notes, opting instead to…

“““html

to stroll around the classroom as she teaches, inviting inquiries and involving individual learners in vibrant, public discussions.

She vividly remembered her own undergraduate challenges — struggling with concepts that appeared straightforward to her classmates. That experience, she mentioned, shapes her teaching methodology today.

“I genuinely enjoy guiding them through concepts,” Maranci shared. “I’m placing myself in their position, wanting to deconstruct topics in a manner that enables everyone to feel capable of grasping this material. Even when it involves the obscure Armenian Church architecture of the 7th century, fundamentally, it’s all attainable knowledge, and that’s a message I strive to convey.”

Michael Smith.

Harvard file photo by Grace DuVal

Active, hands-on engagement with challenges

For Smith, the most effective path to understanding is through action — engaging with tangible issues, resolving technical problems, and confronting ethical challenges.

“Teaching is one of my passions,” he remarked. “I particularly enjoy collaborating with our undergraduate students. I aim to make it as interactive and engaging as possible and link it to the topics that are relevant to the students today.”

Smith has devoted decades to pondering education. He began his teaching journey at Harvard in 1992 and spent 11 years as the dean of FAS. He is currently writing a book focused on teaching methodologies.

A notable instance of his interactive approach is “CS 32: Computational Thinking and Problem Solving,” an introductory course accommodating around 300 students. On the inaugural day, students set up the Integrated Development Environment (a software toolkit for computer programmers) on their laptops to tackle problems alongside the professor. During the concluding weeks, each student delivers a personal project. Some students crafted a program to transform the popular online game Wordle into a version for two players; another developed a program to extract recipes from the web and suggest dinner options based on available ingredients.

“I aim for them to establish a basis upon which they can begin to learn independently and become self-sufficient,” Smith stated.

He applies a similar philosophy in his advanced class, “Critical Thinking in Data Science,” where students confront the ethical ramifications of increasingly powerful information technologies. The class features two-week “sprints,” practices where students create deepfakes and facial recognition applications — grappling with the societal implications of their outcomes. Smith succinctly captured the predicament: “Yes, I can create it, but should I create it?”

Karen Thornber.

Harvard file photo by Grace DuVal

Fostering an inclusive environment for all viewpoints

Thornber, a cultural historian focused on East Asia, aspires to create a classroom atmosphere where diverse perspectives are embraced, enabling students to feel at ease sharing their viewpoints, even on challenging subjects like gender-based violence, mental health stigmas, or end-of-life issues.

Thornber noted that co-chairing the FAS Civil Discourse Advisory Group and becoming the Richard L. Menschel Faculty Director of the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning last year highlighted for her the necessity of cultivating this environment with greater purpose.

“It has made me aware of the significance of attending to students’ tendencies to self-censor or to reach premature agreements,” Thornber remarked. “There is a crucial need for being very deliberate about this and communicating explicitly with the students. If we all enter with the same viewpoint, that’s wonderful, but we will also address differing opinions, as grasping the full spectrum of opinions on difficult issues is essential.”

Thornber’s own research encompasses medical and health humanities as well as environmental humanities, gender justice, indigeneity, and transculturation, relating to the literatures and cultures of East Asia. Her research scope also extends to South and Southeast Asia, alongside Africa, Europe, and North America. This fall she will instruct a novel course titled “HUMAN 2: Introduction to the Medical and Health Humanities.”

She mentioned that shaping a “transformative experience” for students imbues her work with purpose. For her, this means facilitating connections among students and dissolving some of the barriers that segregate learners from diverse backgrounds, allowing for vibrant and fruitful classroom discussions.

“I firmly believe that the humanities equip our students with unique and invaluable insights, perspectives, and information to comprehend and address some of our most intricate global challenges,” Thornber stated. “It’s not only energizing to collaborate with students in expanding their awareness of global issues, but also to assist them in translating this knowledge into meaningful action. Cultivating the hope, enthusiasm, and creativity that students bring — it truly is a privilege and an honor to partake in this process.”

Yuhua Wang.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Learning alongside his students

Wang prefers to structure his political science classes around intellectual debates, illustrating that there is always an alternative perspective to consider. Occasionally, this involves assigning readings and facilitating class discussions that highlight conflicting viewpoints.

“I pose the question, ‘What are your thoughts?’” Wang articulated. “We can critically examine the readings and engage with each other. I believe that the debate format is beneficial for uncovering deeper understanding. By the end of our discussion, we generally gain a clearer insight into the matter and may even shift our prior beliefs regarding the question.”

Wang specializes in Chinese politics and has extensively written on state-building in China from the seventh to the 20th centuries. He is presently conducting comparative research on how China and Europe diverged politically post-1000 AD. His undergraduate courses frequently include “Government and Politics of China” and “Comparative Political Development,” and he participates in a faculty rotation teaching “Foundations of Comparative Politics.”

Wang expressed that his favorite aspect of teaching Harvard undergraduates is the frequent intellectual challenges they pose — which he views as “the best scenario for a professor.” He occasionally presents a controversial standpoint intentionally, encouraging students to challenge him. On several occasions, their insights have prompted him to reevaluate his own stance.

“One aspect I truly wish to convey to them is that I’m learning alongside them — in this class, we are discovering together,” Wang emphasized. “I think this is crucial because I hope they continue their learning journey beyond this course and Harvard. I want them to understand that even individuals my age are still growing in knowledge, and that I can learn from them.”

“`