“`html

Health

Worth the toil

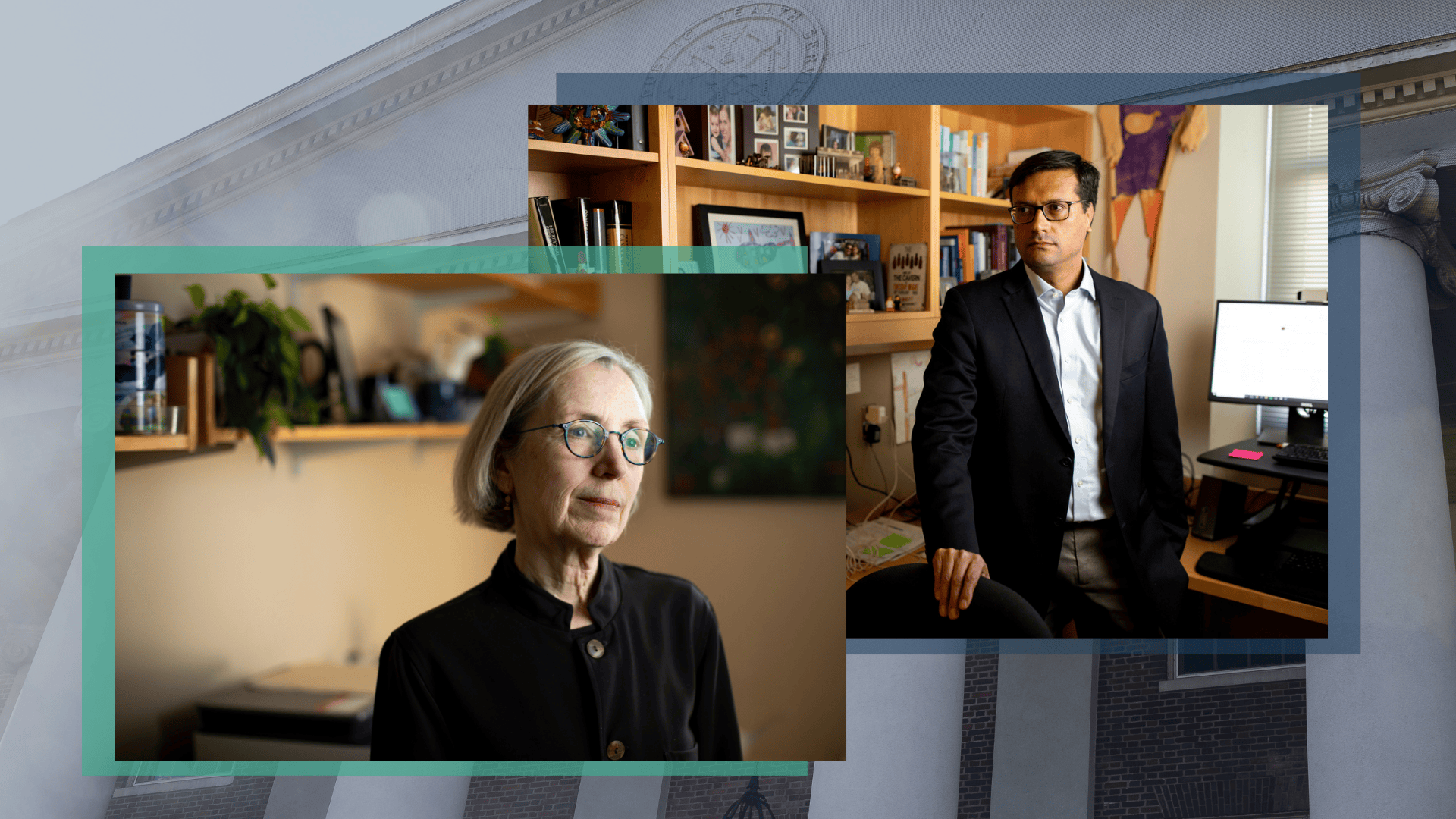

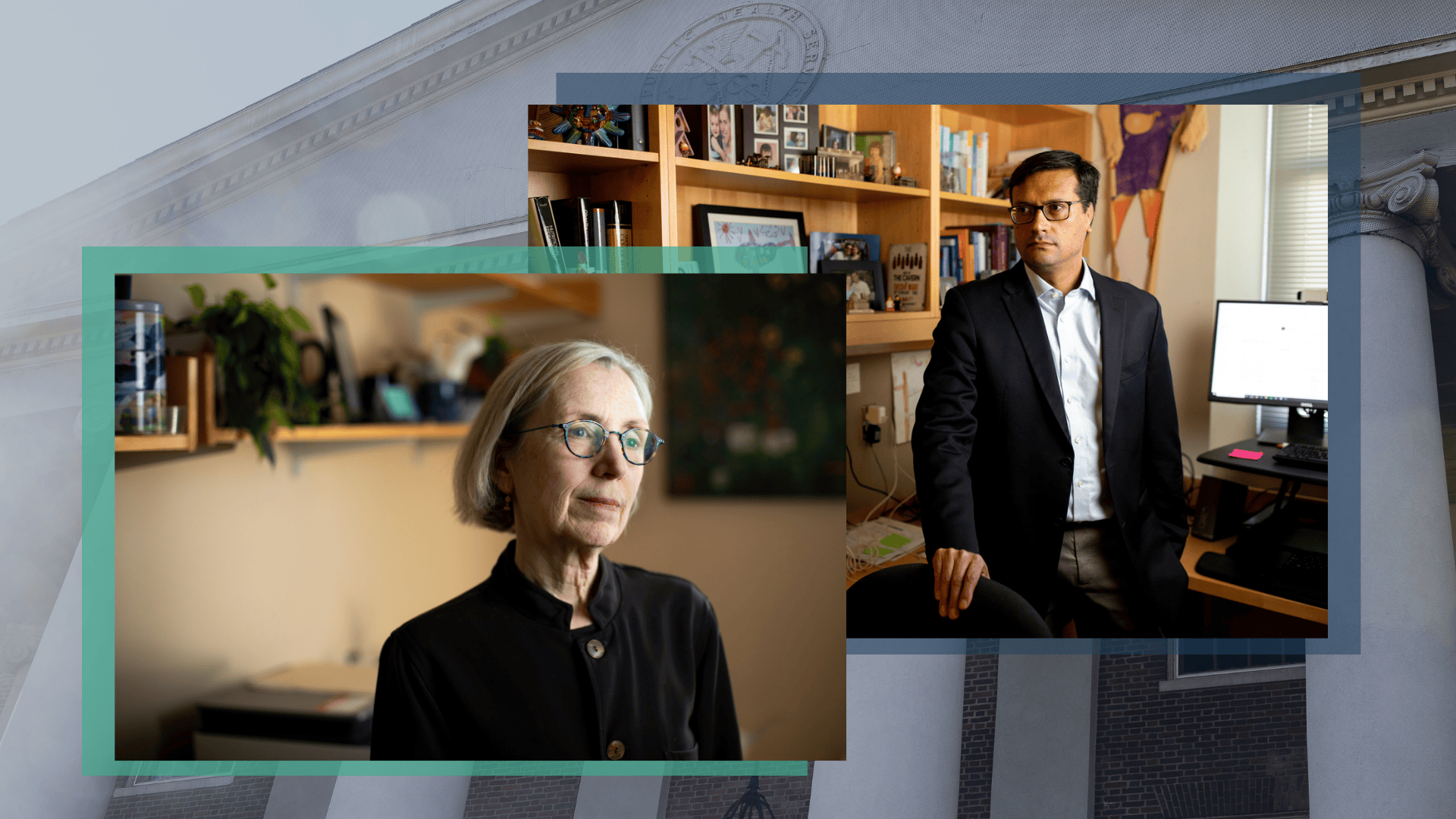

Karen Emmons explores methods to lower cancer risk, while Jorge Chavarro researches nutrition and human reproduction.

Photos by Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer; photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

The arduous task of obtaining a federal grant rewards researchers: ‘It signifies you can take action to assist others.’

For public health investigators, securing a federal grant is a significant achievement.

Over three decades later, Karen Emmons still remembers her initial one. At that time, she was an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Brown University when a letter arrived on green carbon-copy paper, so smudged that she struggled to decipher it. Now a professor of social and behavioral sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, she retains that weathered green document.

“You pursue science because you aim to make an impact, and receiving a grant indicates that you can take initiatives to assist others,” Emmons remarked. “It holds immense significance.”

Such significant moments now face jeopardy. The Trump administration has stalled over $2.2 billion in research grants to Harvard, impeding projects related to neurodegenerative diseases, tuberculosis, and other issues. This governmental action followed Harvard’s refusal to acquiesce to White House requests for viewpoint “inspections” of students and faculty, recruitment changes, and other actions. Recently, the University initiated legal action against the administration.

The suspension of funding disrupts a process that researchers argue is rightly competitive, given the weight of their primary objective: advancements in science and human health.

Jorge Chavarro, a professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Chan School, comprehends the challenges from both perspectives. He applies for grants for his research on nutrition and human reproduction and has spent nearly a decade on a scientific review panel, also referred to as a study section, assessing other researchers’ proposals.

“The NIH genuinely endeavors to guarantee a thoroughly impartial review process for every application,” he stated.

“One cannot merely assert, ‘I have this idea; kindly provide grant funds.’”

For Emmons, who examines techniques to decrease cancer risk in under-resourced areas, the groundwork starts well before the application is drafted. This encompasses nurturing partnerships with community collaborators, keeping abreast of recent publications in her discipline, and maintaining connections with fellow researchers to understand upcoming trends.

“You don’t want to replicate what someone else is already undertaking,” she explained. “You wish to explore uncharted territories.”

Next comes the requirement to validate the idea. The NIH mandates that evidence demonstrates the research is not only novel but also founded on solid reasoning.

“You can’t just assert, ‘I have this concept; kindly grant me funds,’” Emmons stressed.

Writing the application can require another six months, beginning with a one-page summary known in NIH jargon as specific aims, outlining how the study addresses existing voids, its potential impact, and the methodologies to be employed. Following the aims page comes the comprehensive application, which can exceed 100 pages once 12 pages of intricate scientific detail and all necessary administrative documentation are included, Chavarro remarked. It encompasses dense summaries of past work, preliminary research outcomes, thorough methodology descriptions, and a biosketch akin to an academic resume. For Emmons, whose work involves human participants, there are also extensive requirements to ensure the ethical treatment of her subjects. And naturally, there is the budget.

The expense of conducting innovative research has escalated more swiftly than the average amount of a typical grant, Chavarro noted, effectively necessitating that scientists be increasingly resourceful with the same funding. Thus, every detail in the budget demands justification. “Why is acquiring a new piece of equipment that you lack significant?” he queried. “What is the necessity for funds for tubes or pipettes, liquid nitrogen?”

Upon submission, applications are allocated to Scientific Review Groups composed of volunteer scientists capable of evaluating the research based on its merits. Study sections score proposals against one another for their creativity, significance, and approach. Subsequently, advisory councils for each institute conduct a second-level review to ascertain whether the studies align with their organizational missions. The two evaluation phases are synchronized, and only the most promising projects receive funding.

Success rates differ among institutes, but at the National Cancer Institute, where Emmons submits the majority of her applications, there was a 14.6 percent success rate for the most prevalent type of grant, the R01, in 2023, according to the latest data available. This indicates that after months or years of preparation, pilot studies, partnership facilitation, and budget negotiations, merely one in six proposals will receive funding. Researchers whose submissions are unsuccessful can incorporate feedback and reapply.

Both Chavarro and Emmons recognize that the process can be exasperatingly sluggish. They believe that the thoroughness of the approach is part of what renders it exceptional. Emmons highlighted the longstanding public-private alliance between universities and the government as a mutual commitment to science as a societal benefit.

“Early on, the government recognized that it serves society and, in turn, benefits the government: It promotes better health, grants people access to lifesaving treatments, and diminishes the costs associated with caregiving during illnesses,” she elaborated. “It’s fundamentally what the government ought to do: It should assist the populace.”

“`