“`html

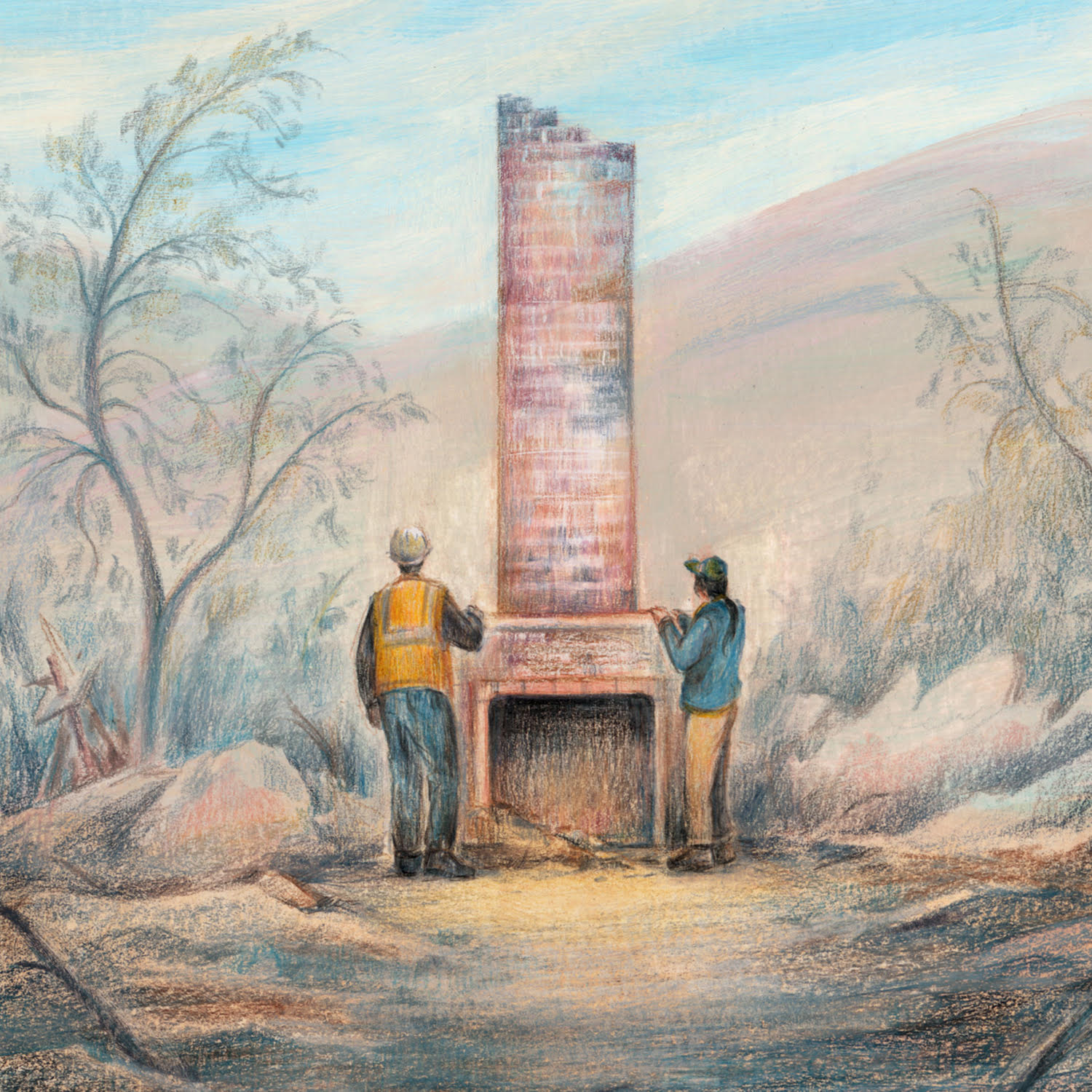

Following the wildfires, the necessity has never been greater for USC scholars to implement innovative approaches that significantly advance sustainability, community participation and the reimagining of Los Angeles. (Illustration/Sally Deng)

Environment

Rebuilding Los Angeles

USC specialists provide their insights on how residents can reconstruct their neighborhoods more resilient and improved after the wildfires in January.

As celebrated architect Peyton Hall glanced out from his window and across the street from his Sierra Madre residence on Jan. 7, he observed a sprawling orange illumination in the sky: The Eaton fire was approaching. The magnitude of the catastrophe became evident as the flames advanced, prompting Hall to escape alongside his neighbors from the encroaching disaster. After 26 years of instructing heritage conservation programs at the USC School of Architecture, the situation transformed from professional to personal as he envisioned the requirements to restore his community following a devastating wildfire.

“I’ve witnessed many significant events during my 45 years in Los Angeles,” Hall remarks. “This surpasses all in terms of significance, immediacy, and challenge. It’s beyond words.”

The January 2025 Eaton and Palisades wildfires are expected to be recorded as one of the most catastrophic and costly natural calamities in our country’s history. The threefold threat of consecutive wet winters that encouraged vegetation proliferation, unprecedentedly low autumn rainfall, and a considerable Santa Ana wind event created intense fire conditions. The largest wildfires ultimately claimed 29 lives, scorched over 37,000 acres, demolished more than 16,000 buildings, and imposed mandatory evacuation orders on over 150,000 individuals.

As Angelenos — particularly those residing in Altadena and Pacific Palisades — strive to recuperate from the wildfires’ severe effects, uncertainties linger: What is the most effective method to reconstruct? And is it possible to achieve this swiftly, sustainably, while retaining the unique traits of what was lost?

I’ve witnessed many significant events during my 45 years in Los Angeles. This surpasses all in terms of significance, immediacy, and challenge. It’s beyond words.”

Peyton Hall, USC School of Architecture

In the aftermath of the wildfires, the stakes have risen significantly for USC researchers and practitioners across various fields to implement innovative strategies that advance sustainability, community involvement, and the reimagining of a city renowned for its capacity to reinvent itself repeatedly.

USC professors with specialization in vital domains like air and water quality, healthcare, landscaping, soil integrity and contamination, population density, building regulations, and individual conduct, among other research sectors, can greatly influence the understanding of the factors that resulted in this level of devastation — and what modifications are necessary to avert future occurrences.

Constructing for the future

In 2018, architect Geoffrey von Oeyen, head of von Oeyen Architects and Geoffrey von Oeyen Design, had just completed a redesign of a house for his brother in their hometown of Malibu when the Woolsey wildfire ignited. The inferno ravaged the Malibu region and obliterated the home while von Oeyen assisted his brother and parents in evacuating the area. Having tracked the week’s wind patterns via a weather app, he was aware that a wildfire was a possibility.

“I grew up fleeing from fires as a child, so I already understood the emotions involved,” recounts von Oeyen, an associate professor of practice at the USC School of Architecture since 2012. “However, the Woolsey fire was so immense and so fierce that it surged through all of the Santa Monica Mountains almost simultaneously.”

Restrictions on permits for the original residence — a ranch-style house from the 1960s — constrained the design techniques von Oeyen could utilize during the renovation. The structure featured elements that made it ideal fuel for a wildfire, such as wooden fences, a wooden retaining wall, and a ventilated attic that allowed embers to infiltrate the home and ignite.

When he reconstructed the home last year, von Oeyen was free to implement various strategies to reduce wildfire danger. He opted for insulated roofing in place of a ventilated attic; established a concrete retaining wall to protect the home from its wildland boundary and the adjacent house; and constructed a driveway made of concrete, rocks, and gravel. He also refrained from planting large vegetation near the residence.

“We concentrated on sustainable features of the house that could enhance fire resistance, such as natural ventilation, ensuring we don’t have a house mechanically drawing in large amounts of air — and possibly embers — into the ductwork,” von Oeyen explains.

Additional upgrades included a generator positioned within a concrete bunker and a sprinkler system that, once initiated, will utilize city water before seamlessly switching to supply from the home’s pool when municipal water pressure diminishes. The sprinkler system is connected to the roof and designed to drench both the landscape and the entire house.

The Franklin fire, which occurred a few weeks prior to the Palisades fire, created a burn scar in central Malibu that prevented the Palisades fire from extending west of Malibu, where the newly reconstructed home resides. While von Oeyen recognizes that some of these improvements might exceed the financial capacity of many Californians, he contends that newly constructed and existing homes targeted in the rebuilding process, as well as throughout the state, need to be retrofitted for wildfire safety regardless of their setting.

“Why aren’t we incentivizing individuals to construct resiliently, ensuring we don’t face challenges in the future when fires inevitably move through neighborhoods situated far from wildlands?” queries von Oeyen, whose younger son’s school in the Pacific Palisades partially burnt down in January. “That would lead to fewer homes ignited. This means there would be fewer insurance claims, reduced FEMA expenses, and diminished emergency relief funding from the state. We would be investing in the future.”

He further asserts that sustainability must be integral to any discussion surrounding the reconstruction efforts. “If we continue employing carbon-intensive building techniques, we will worsen the atmospheric conditions that result in more frequent and intense climate events, such as wildfires,” he remarks.

Why aren’t we incentivizing individuals to construct resiliently, ensuring we don’t face challenges in the future when fires inevitably move through neighborhoods situated far from wildlands?

Geoffrey von Oeyen, associate professor of practice at the USC School of Architecture

Rebuilding to endure

Professor Bora Gencturk of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering indicates that one of the pivotal aspects accelerating wildfire spread in both Altadena and the Pacific Palisades is the fact that in the United States, over 90% of residential constructions — particularly single-family homes — utilize wood for framing and other elements due to the widespread availability of timber. In comparison to other parts of the globe, like the Middle East or certain regions of Africa — which depend on less flammable materials such as reinforced concrete — most U.S. homes are ill-equipped to handle the wildfire threats endemic to California.

“It is critical for us to assess alternative materials, even if they are conventional ones, that are resistant to wildfires,” states Gencturk, who also heads the Structures and Materials Research Laboratory at USC Viterbi’s civil and environmental engineering department. He posits that materials like concrete and its variants are non-combustible, won’t emit smoke when exposed to flames and won’t generate embers capable of spreading fire from one roof to another far from the original wildfire source — thus making them significantly easier to manage when ignited.

Gencturk notes that roofs serve as the primary defense a dwelling possesses against a wildfire.

“With wildfires, wind plays a significant role as it carries embers, which predominantly land on the roof because it presents the largest surface area,” Gencturk observes. “It is evident that fire generally infiltrates homes via the roof. However, if we can construct our roofs using fire-resistant and lightweight materials, this will aid in minimizing the extent of damage.”

Numerous roofs in California are constructed with shingles crafted from substances such as paper and petroleum-derived products, which combust rapidly upon contact with embers. Gencturk advocates that Californian homes should transition to roofing materials like clay, metal, or other innovative technologies, such as composite cladding — a mix of reclaimed wood fiber and recycled plastic that serves as an additional shield to protect the exteriors of buildings from severe weather conditions. Fire-rated windows can also provide a protective layer due to their capability to withstand high temperatures and prevent the transfer of smoke and flames.

Gencturk also emphasizes that reducing excess vegetation and potential fuel sources near buildings, as well as creating concrete barriers or spacing between structures, can significantly alleviate the risk of fire spread.

Architect Liz Falletta, a USC Price School of Public Policy professor, concurs. She asserts that establishing a greater distance between residential properties and wildlands is a strategy that should be considered in the reconstruction. She notes that denser housing — particularly in Altadena — is essential.

“You could develop housing that is denser and taller but with the same number of units further down the hill, thereby conserving the remainder of the land as communal open space with fire-resistant landscaping,”

“`

The South Pasadena inhabitant states. “This approach ensures we won’t need to construct in regions where urban neighborhoods intersect with natural landscapes.”

Falletta contends that such multifamily residences can cultivate a stronger sense of community and encourage more sustainable land management. Additionally, from a fairness and cost perspective, “We’re going to have to construct densely one way or the other,” she comments. “If we aim to be a just city, single-family dwellings will be unattainable for most Angelenos.”

Building our roofs with materials that are both fire-resistant and lightweight will help mitigate the level of destruction.

Professor Bora Gencturk, USC Viterbi School of Engineering

Safeguarding the spirit of a community

As a historic architect, Hall recognizes the vital attributes of structures, neighborhoods, and cities. He employs the idea of a “palimpsest” to illustrate the layers of information contributing to a neighborhood’s character—encompassing architectural styles, landscapes, streets and walkways, as well as the density of residential, retail, and community spaces. He underscores that following these calamities, it’s “everyone’s responsibility” to consider these layers collectively.

In the haste to reconstruct, much may be lost without deliberate planning.

“We identify as architects due to our engagement with physical landmarks and buildings, but we also discuss people and community,” Hall expresses. “It’s about maintaining cities to ensure that residents want to inhabit them, recognizing their roots in community and family. The tangible aspect of constructing or reconstructing a building serves merely as a means to support the less observable elements that define a neighborhood and a community.”

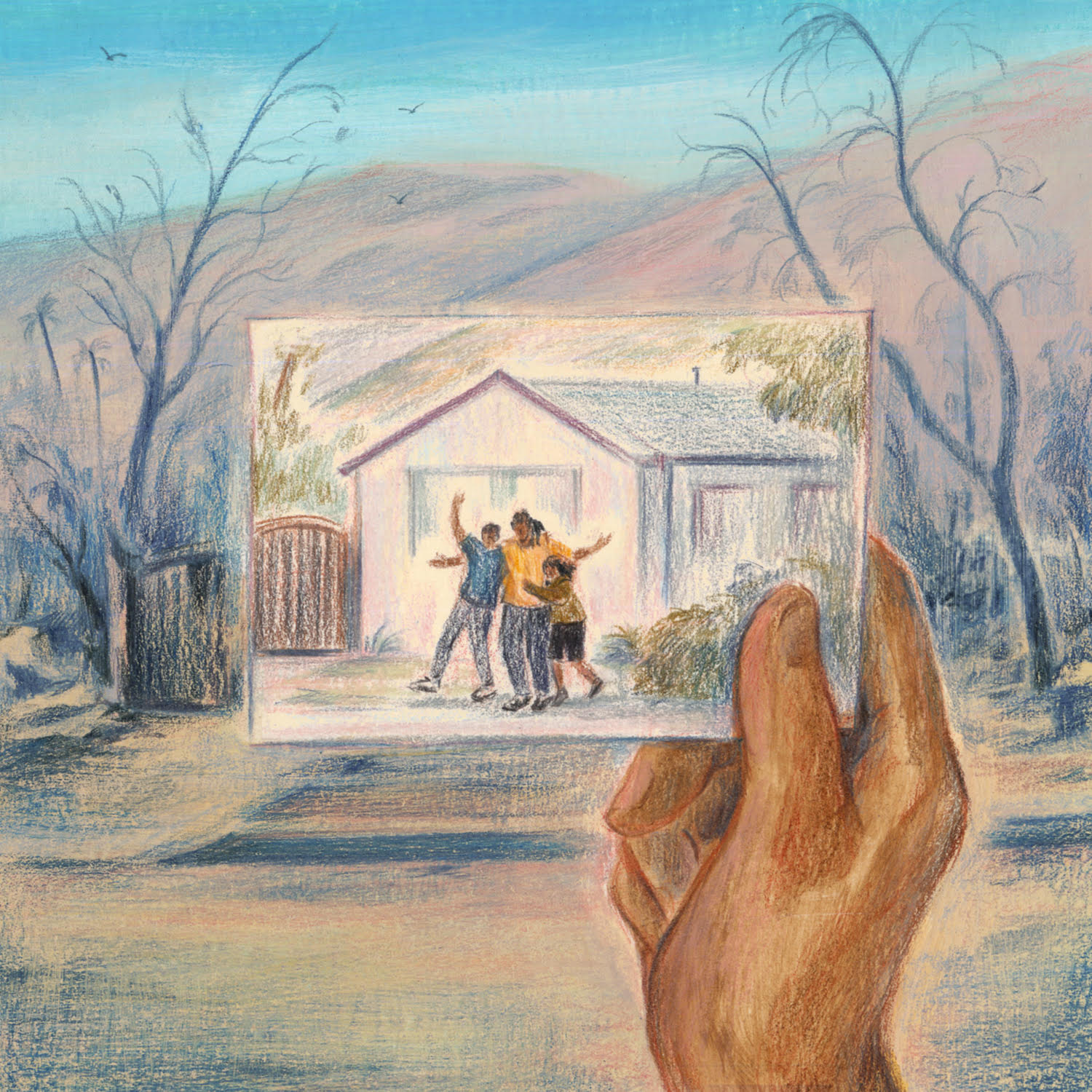

Hall recalls a conversation with a colleague whose home stood firm against the wildfire in the Palisades. Although her residence remained intact, many of her neighbors lost theirs, along with the shops, churches, and schools frequented by them and their families.

He argues that a residence devoid of a community hardly counts as a real home. “It’s integral to their overall well-being,” Hall says. “It’s beyond merely, ‘We lost our church, we lost our home.’ It’s more accurately, ‘We lost everything that binds us to the individuals we know, and everything we understand and grew up with.’”

Hall aims to remind those engaged in the Altadena and Pacific Palisades rebuilds that urgent action does not necessitate sacrificing the preservation of the history and character of the communities. “A home built in 1908 should not be reconstructed in the same manner a hundred years later,” Hall insists. “And genuinely, we don’t desire that. This is a mandated opportunity to create something that is more energy-efficient yet still possesses good character and compatibility.”

Participating in decision-making

Urban planner and researcher Santina Contreras commenced her work in housing reconstruction and disaster response in countries susceptible to earthquakes like Haiti and Indonesia. Through her experience, she recognizes that irrespective of the disaster, community engagement is frequently the first aspect of the recovery process to be compromised for the sake of expediency—a blunder she believes can entail hidden costs in the future.

“You could find a scenario where all the houses are rebuilt, but if it doesn’t resemble or evoke the same feelings as before, if the previous residents aren’t able to return—was that truly a success?” Contreras questions.

As an assistant professor of urban planning and spatial analysis at USC Price, Contreras investigates the power dynamics inherent in involving community members during and after disasters and how this practice can foster greater equity in the recovery phase.

You could find a scenario where all the houses are rebuilt, but if it doesn’t resemble or evoke the same feelings as before, if the previous residents aren’t able to return—was that truly a success?

Santina Contreras, USC Price School of Public Policy

Contreras asserts that numerous recovery initiatives she has participated in often lacked frequent and effective opportunities for “two-way communication” with community members to engage them in and inform the process, resulting in recovery outcomes that fail to align with the needs and interests of those communities.

To counter this, she advocates for providing affected communities a seat at the decision-making table through consistent opportunities for engagement, such as community gatherings and focus groups for input collection, as well as workshops to bridge informational gaps, update residents on available resources, and keep them informed about ongoing processes and what lies ahead.

Contreras emphasizes the importance of listening to feedback, utilizing it to adapt and inform recovery actions, and continually returning to check on identified goals as crucial next steps.

“Remaining receptive to this process is vital because what suits Altadena will differ from what benefits the Pacific Palisades,” she notes. She also cautioned about the necessity of clarity regarding expectations versus reality. “Unfortunately, it’s challenging to envision a rebuilt L.A. exactly mirroring its former appearance—but there also exist opportunities for rebuilding in a superior manner and discussions about what that might entail.”

Contreras shares that she has engaged in dialogues with fellow researchers and practitioners to discover methods to combat gentrification and exploitative rent increases by equipping residents with resources that clarify their future options and inform their decision-making throughout the extensive rebuilding process.

“Collectively, we have many common interests,” Contreras articulates. “However, each community is unique and possesses its own apprehensions. This emphasizes the necessity of prioritizing comprehensive discussions with community members regarding their needs and interests. This will optimally position us for achieving the most equitable recovery outcomes over the long term.”

Anticipating the future

All researchers concur that investing in resilient design and construction now will prove to be more economical than addressing the expenses of cleanup, recovery, and rebuilding later on.

“Federal and state resources should be allocated via grants and tax incentives to reconstruct these communities resiliently as an investment in the future,” von

Oeyen states, “Both the federal and state authorities, along with private insurers, could save billions in the long run if communities manage to endure the unavoidable wildfires that are expected to become more common and intense as time progresses.”

Gencturk is optimistic about the prospects for weather-adaptable home construction. He is currently developing a method that employs a construction robot to layer concrete via a 3D printer. He leads a committee under the International Code Council that aims to create a code of standards for 3D-printed construction practices. He hopes to have this method accessible to Californians by 2030.

As the reconstruction continues in the coming months and years and the risk of wildfires remains elevated in California and beyond, politicians, vital stakeholders, and residents near and far from fire-prone areas should picture a future of sustainable land usage, durable construction, and fortified communities.

The alternative—rebuilding without heeding the lessons of prior disasters—could result in devastation and loss far more extensive than what has been witnessed before.

“I look out my window now, and I see charred hills,” Hall remarks. “When I hear helicopters, I scan the surroundings for fire. There’s a new sense of caution, a renewed awareness about our living conditions.”

How are Trojans playing a role in L.A. wildfire assistance initiatives?

Faculty from USC in essential domains such as air and water quality, healthcare, landscaping, soil integrity and pollution, and population density, among various research fields, are applying their knowledge to participate in an extensive range of L.A. wildfire assistance initiatives.

- Through the Los Angeles Fire Human Exposure and Long-Term Health Study (L.A. Fire HEALTH Study), faculty from the Keck School of Medicine of USC are collaborating with researchers from UCLA; the University of California, Davis; the University of Texas at Austin; Harvard University; Stanford University; Yale University; and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center to evaluate the health consequences of wildfire emissions and investigate “which pollutants are present, at what concentrations, and in which locations, as levels decrease over time.”

- Public Exchange, affiliated with the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, has initiated a “community-led initiative” to assist residents from wildfire-impacted regions in testing their soil for lead levels at no charge. Its Contaminant Level Evaluation & Analysis for Neighborhoods (CLEAN) project aims to create an interactive map illustrating sample sites and lead concentrations throughout the affected regions.

- Through Project Firestorm, Professor Frank Gilliland from the Keck School of Medicine of USC and his colleagues are embarking on a “swift-response epidemiological study” to assess the health effects of urban-wildfire interactions. This research will involve a cohort of 9,000 participants from USC drawn from a previous COVID-19 study.

- USC Visions and Voices hosted “After the Flames: The Role of the Artist in Climate Justice and Sustainable Change,” a collaborative effort between the USC Thornton School of Music and USC Arts Now. This half-day symposium and teach-in, held on April 21, centered on the effects of the wildfires and the interplay of creativity, climate justice, and sustainability.

- The USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research launched the LABarometer Wildfire Survey. Its results offer “the first comprehensive view of how Angelenos were impacted by the wildfires based on their housing stability and income prior to the events.”

- The USC Rossier School of Education, in collaboration with the USC College Advising Corps and the USC Leslie and William McMorrow Neighborhood Academic Initiative, conducted a seminar about the college admissions procedure for high school seniors affected by the L.A. wildfires.

- Monalisa Chatterjee, an associate professor of environmental studies at USC Dornsife, is collaborating with graduate student researchers from the school’s environmental studies and environmental data science programs to analyze California’s fire insurance market and address “the challenges of creating a new framework by examining large datasets and engaging with communities in high-risk zones.”

- The Trojan Family Relief Fund assists USC students, faculty, and staff who have been displaced by the fires and require support with transitional expenses, including temporary housing, family care, and emergency necessities.