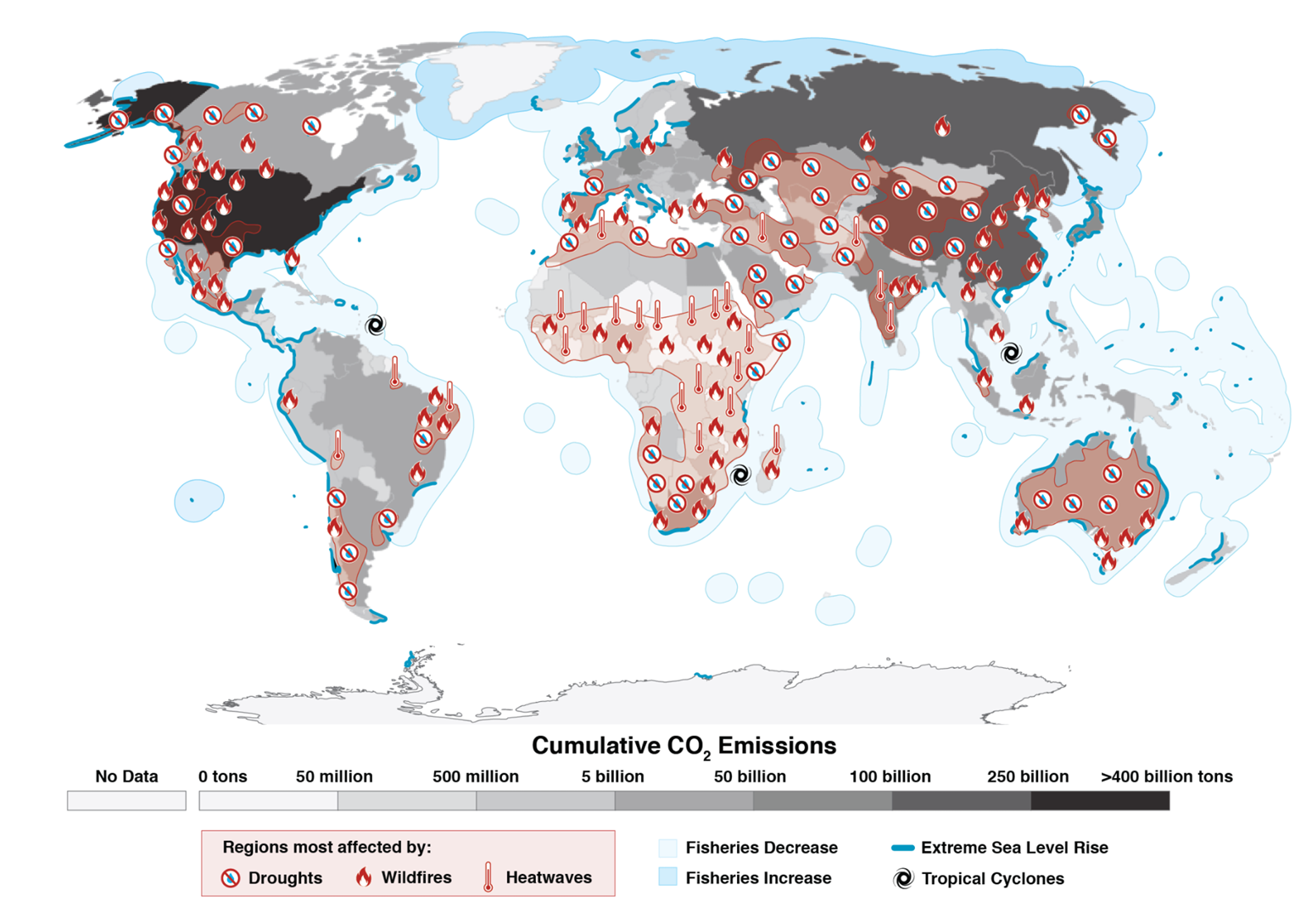

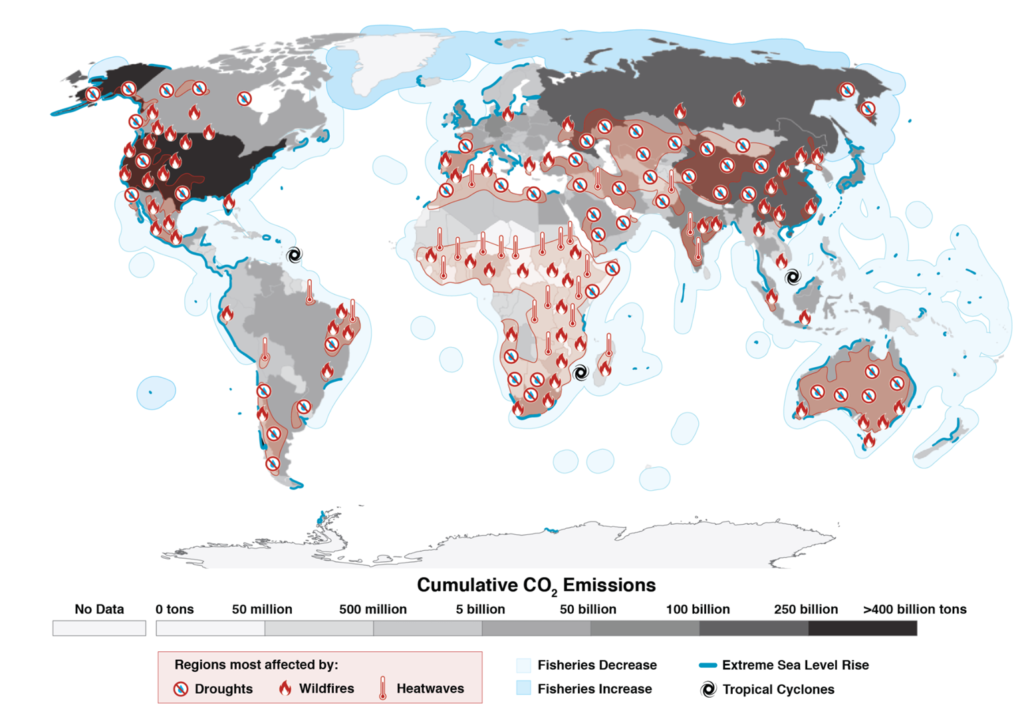

As evidence mounts indicating that the repercussions of climate change disproportionately impact marginalized communities globally, there are also numerous accounts highlighting how these communities incur substantial costs to implement climate solutions.

However, an investigation into the existing collection of data and literature detailing the rollout of climate change mitigation strategies across various nations, led by the University of Michigan, has uncovered reasons for hope.

“It’s not all despair and pessimism,” remarked report author Peter Reich, a professor at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, or SEAS, and head of the Institute for Global Change Biology.

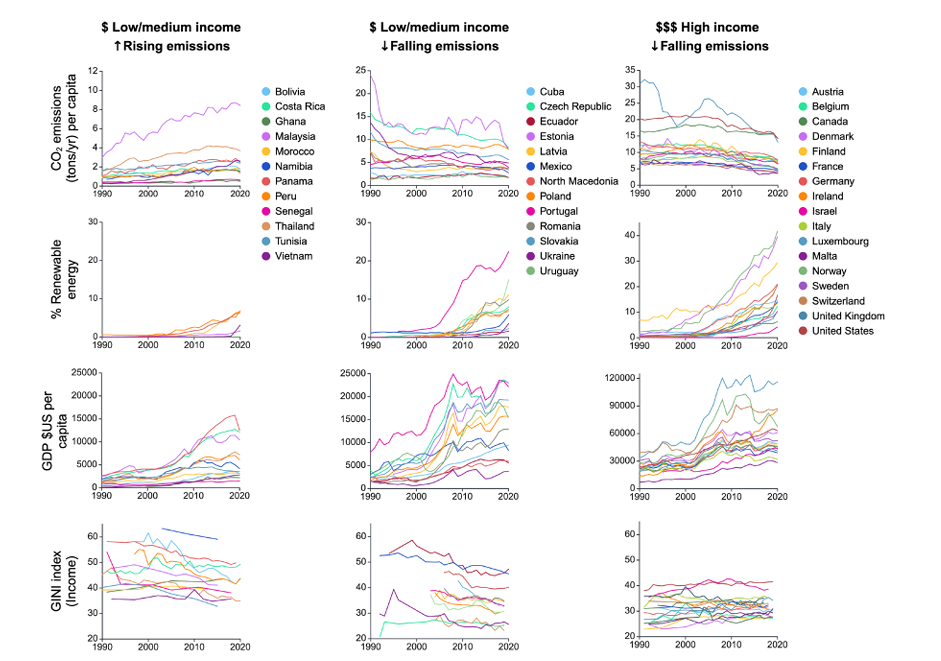

“There’s an assumption that poorer nations must produce pollutants to achieve a middle-class lifestyle for their people, as we have. Yet we’ve observed numerous low-middle-income nations begin decarbonizing by investing in renewable energy and enhancing energy efficiency. They are decreasing emissions while narrowing income disparity and improving their citizens’ quality of life.”

Nevertheless, Reich noted that it’s all too simple to find instances where disadvantaged communities suffer adverse effects from investments in renewable energy. For example, Indigenous populations displaced for the creation of a hydroelectric dam illustrate this point. In fact, this scenario inspired the recent study.

Hundreds of research articles and numerous pages within Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports underscore such disparities. These inconsistencies appear both in the repercussions of climate change and in the mitigation approaches utilized to reduce it. Reich and his team aimed to derive broader insights by systematically integrating individual reports into a comprehensive analytical framework.

In their latest report, the team investigated links between climate consequences, mitigation tactics, and social equity elements, including wealth distribution, public health, and general well-being.

While their endeavor revealed that some nations performed better or worse on specific criteria, the researchers’ goal was not to rank, commend, or criticize. Instead, they sought to answer a more fundamental inquiry: Is there evidence to support the possibility of developing sustainable policies and infrastructure in a fair manner?

“Since inequality can arise from the mitigation actions themselves, this can sometimes create a negative effect that hinders the broader adoption of such strategies,” noted Reich, who is also a professor at the University of Minnesota.

This delay has contributed to a pervasive belief that asking impoverished nations to transition to renewables equates to asking their citizens to endure hardship, he stated.

“However, there’s no consistent evidence indicating that the shift to renewable energy has adverse effects or repercussions for poorer nations or their populations,” Reich remarked. “When countries manage to invest in renewable resources, we observe situations where it indeed benefits their citizens, lowers pollution levels, and mitigates climate change. It’s a win-win-win.”

As a case in point, the researchers discovered thirteen low-to-medium-income nations that have been expanding their renewable capacity alongside rising average incomes and gross domestic product per capita over the past three decades. These nations also experienced decreases in their emissions and Gini coefficients, which measure inequality.

“We’re not asserting that all this is causally linked,” Reich clarified. “Yet there’s no evidence suggesting that renewable energy obstructs equity or economic progress.”

The results of the research were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

An additional significant aspect emphasized by Reich is that this does not absolve affluent nations with high emissions, like the U.S., from their responsibilities. They must intensify their efforts to decarbonize to achieve global climate objectives, he stated, but he believes the economic data will urge them into action.

“Each decade that we postpone action sees the astronomical rise of climate change damage costs, while the expense of renewables continues to decline,” Reich pointed out. “This isn’t merely my opinion, as an ecologist, fabricating figures. These statistics originate from major corporations and insurance providers tasked with assessing risks.”

Although he acknowledges that time may eventually prove him incorrect, Reich approaches the findings of the team’s study with optimism.

“We’re not naive idealists. The international community has yet to resolve this matter and will not rectify it overnight,” he stated. “However, we can decelerate and ultimately halt climate change, achieving this while also saving finances and advancing environmental equality.”

The research team included Kathryn Grace from the University of Minnesota, Narini Nagendra from Azim Premji University in India, and Arun Agrawal from the University of Notre Dame. Agrawal is also an emeritus professor at SEAS.