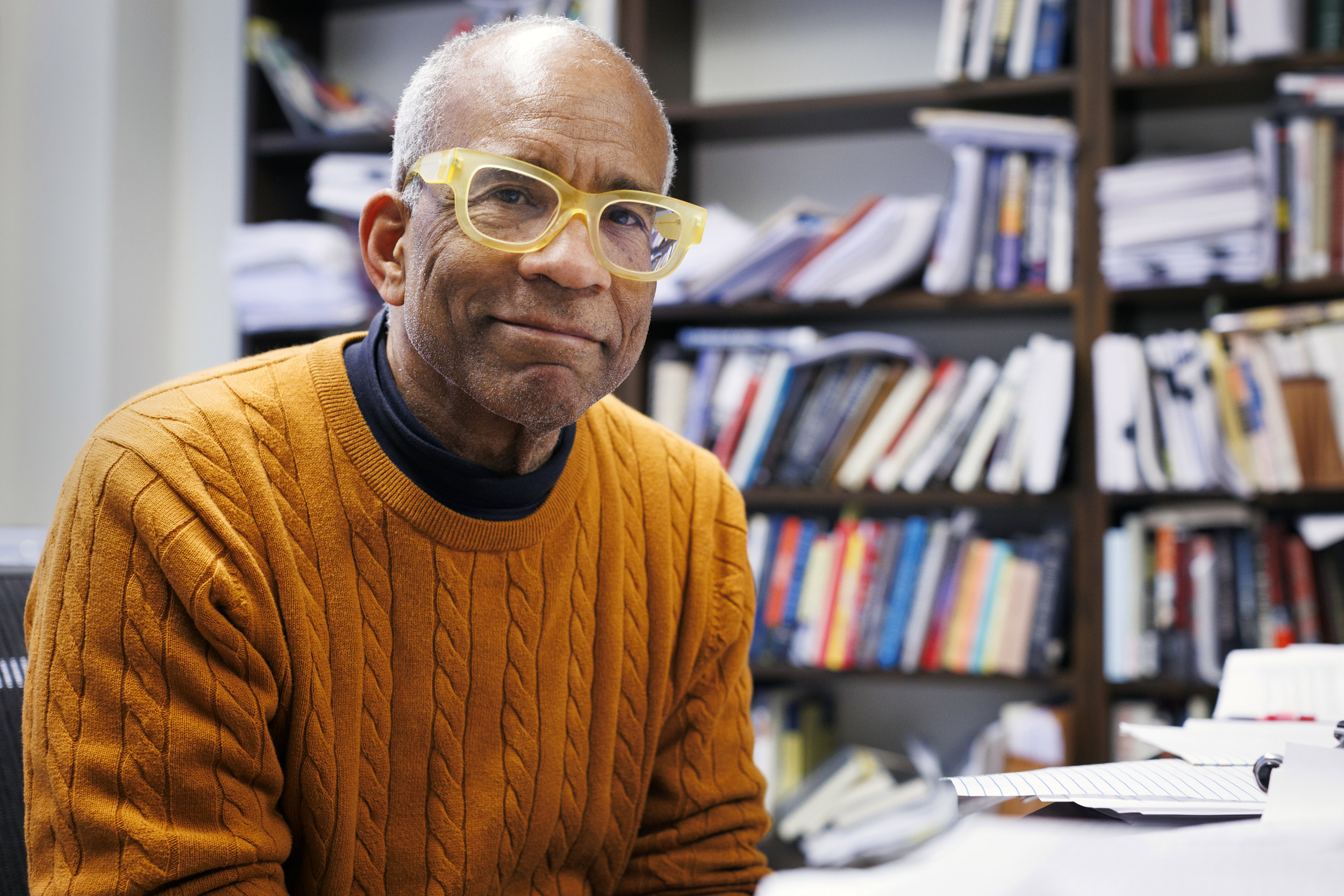

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Nation & World

‘If you’re dull, you’re not going to educate.’

Randall Kennedy has tread a remarkable path as an open-minded, nuanced, and independent thinker

Part of the

Experience

series

Academics at Harvard share their narratives in the Experience series.

Attorney and legal scholar Randall Kennedy can justifiably be labeled as somewhat of an iconoclast.

Recognized as a public intellectual, he is acknowledged for his receptiveness to various perspectives, as well as his nuanced and occasionally controversial views on topics such as affirmative action (there are drawbacks along with advantages), racial profiling (not entirely unreasonable but ultimately biased), Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion statements (discard them), and other matters typically linked to the left.

Kennedy, the Michael R. Klein Professor of Law, has also shown a willingness to confront views from the right. In 2020, the conservative Manhattan Institute invited Kennedy, a long-time skeptic of critical race theory, to engage in a discussion regarding the subject. He eventually challenged fellow CRT critics during the panel for being overly dismissive.

“The remarkable aspect of his work is that it is impossible to anticipate his stance — on racial justice, he may appear conservative at times, and at other moments liberal,” remarked then-Law School Dean Martha Minow in a 2013 feature about Kennedy. “In his area of race and the law, he stands alone in the legal academy. I don’t know anyone else who possesses his dedication to pursuing the truth regarding contentious issues regardless of where it leads.”

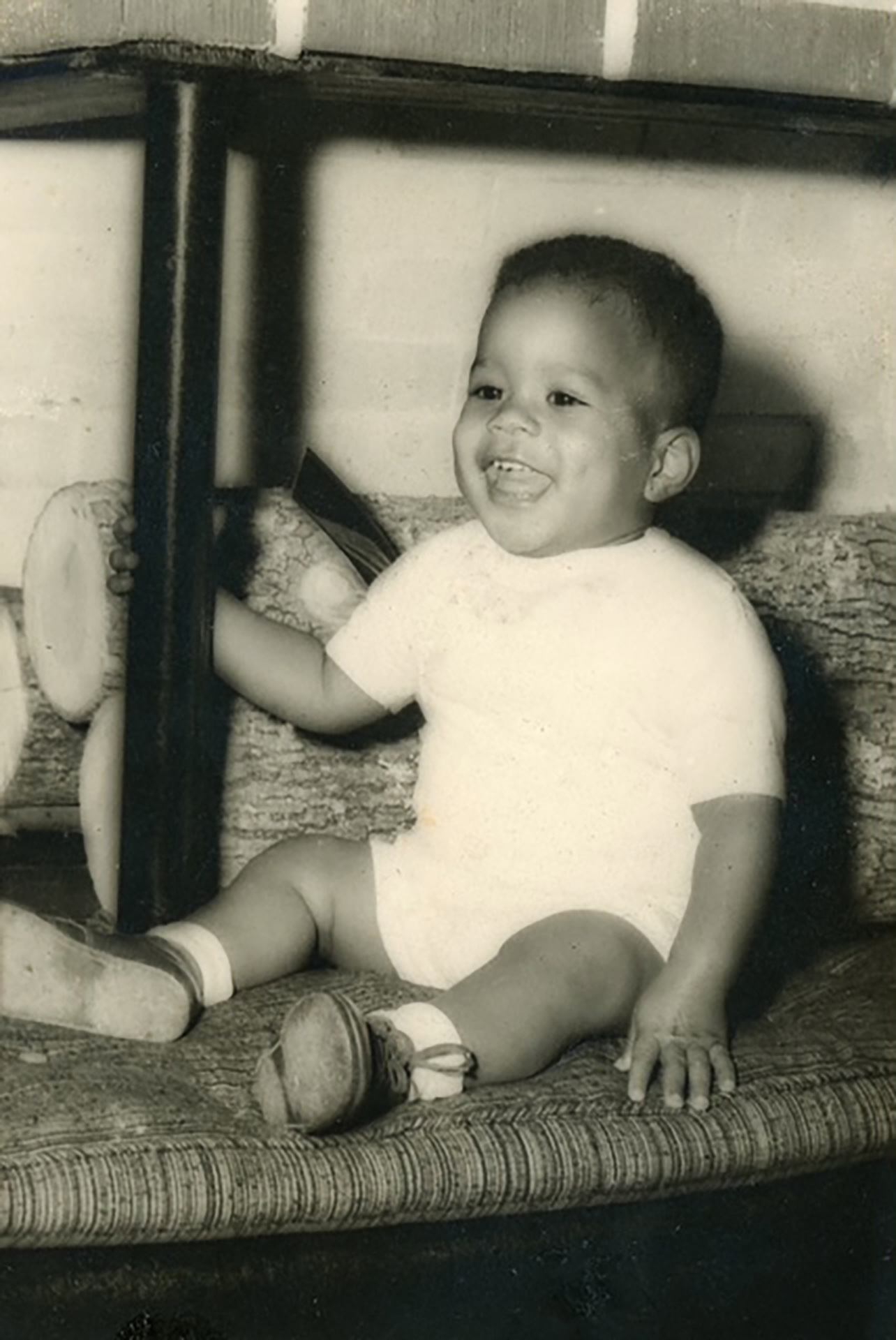

Kennedy, aged 70, was born in Columbia, South Carolina, and grew up in Washington, D.C. His family’s relocation from the Jim Crow South, accompanied by his father’s gloomy outlook on the future of enduring racial justice in the U.S., has profoundly shaped Kennedy’s intellectual journey.

The child of a postal worker and a schoolteacher, Kennedy attended the esteemed St. Albans School, completed his undergraduate education at Princeton, and was a Rhodes Scholar. He attended Yale Law School and has been teaching at Harvard since 1984. As the author of seven books, Kennedy recently conversed with the Gazette concerning his life, career, and perspectives on racial equality in the U.S. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What motivated your father to relocate the family from Columbia to D.C.?

My parents were fugitives from the Jim Crow South. My father hailed from Louisiana, while my mother was from South Carolina. They met at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, during World War II.

In the mid-’50s, shortly after my arrival, they decided to leave. An occurrence instigated their departure. It involved my father. He carried a firearm as part of his job driving a postal truck. In a small town in South Carolina, a white police officer stopped him. The officer stated, “We don’t permit negroes to possess guns. Hand yours over.”

My father declined, resulting in a standoff. He quickly left that situation, made it to Washington, D.C., called my mother, and announced, “We’re relocating.” Years later, I inquired why he decided to leave despite the fact they had just constructed a house outside of Columbia. He remarked, “I believed that if we did not move, I was going to kill a white man, or a white man would kill me.”

Did you face discrimination during your upbringing?

Indeed. The most significant instances occurred during travels from D.C. to South Carolina for holidays. Even as a child, I felt the atmosphere shift as soon as we crossed the 14th Street Bridge from D.C. into Virginia.

I recall several occasions when the police stopped my father while we were traversing Jim Crow areas. The scenario remained consistent. An officer would halt our vehicle. My father would inquire, “Is there an issue, officer?” and the officer would respond, “No, there’s no issue. I stopped you because I saw you have Washington, D.C., license plates, and I wanted to make you aware that we operate differently down here.”

The officer was testing my father, and my father acquiesced. He complied with what the police officer desired, and what the officer wanted was for my father to refer to him as “sir,” being submissive, indicating that my father understood his place.

My father acted as expected, and we continued our journey. God bless my father for that! He prioritized his family’s well-being above all else. If it meant suppressing his pride to achieve that goal, so be it. What commitment. What grace. What discipline. What love. Indeed, God bless my father for that.

In what manner did your parents’ perspectives on race influence you?

Theyinfluenced me profoundly in numerous ways, some of which are undoubtedly beyond my conscious awareness. One significant influence was my father’s profound pessimism regarding the potential for enduring racial equality in America. He held the belief that the United States was designed to be a dominion for white males and would perpetually remain so, and he never reconciled with the nation for its injustices toward African Americans.

During his funeral, as a veteran, a representative from the U.S. military presented a neatly folded American flag to my mother. I distinctly remember sharing a smile with my brother amidst the tears. We both recognized that our father would have found the situation uproariously amusing because he was far from a patriot. He was quite the anti-patriot. Understanding the sense of grievance he experienced has been a significant aspect of my intellectual journey.

What recollections do you have of your childhood?

I enjoyed a delightful childhood! I spent several summers in Columbia, South Carolina, where I stayed with my Aunt Lillian. I had a splendid time, even though during some summers, public parks were not accessible. Why? Because South Carolina opted to shutter public parks rather than witness their desegregation. Nevertheless, I had many friends and we had a lot of fun.

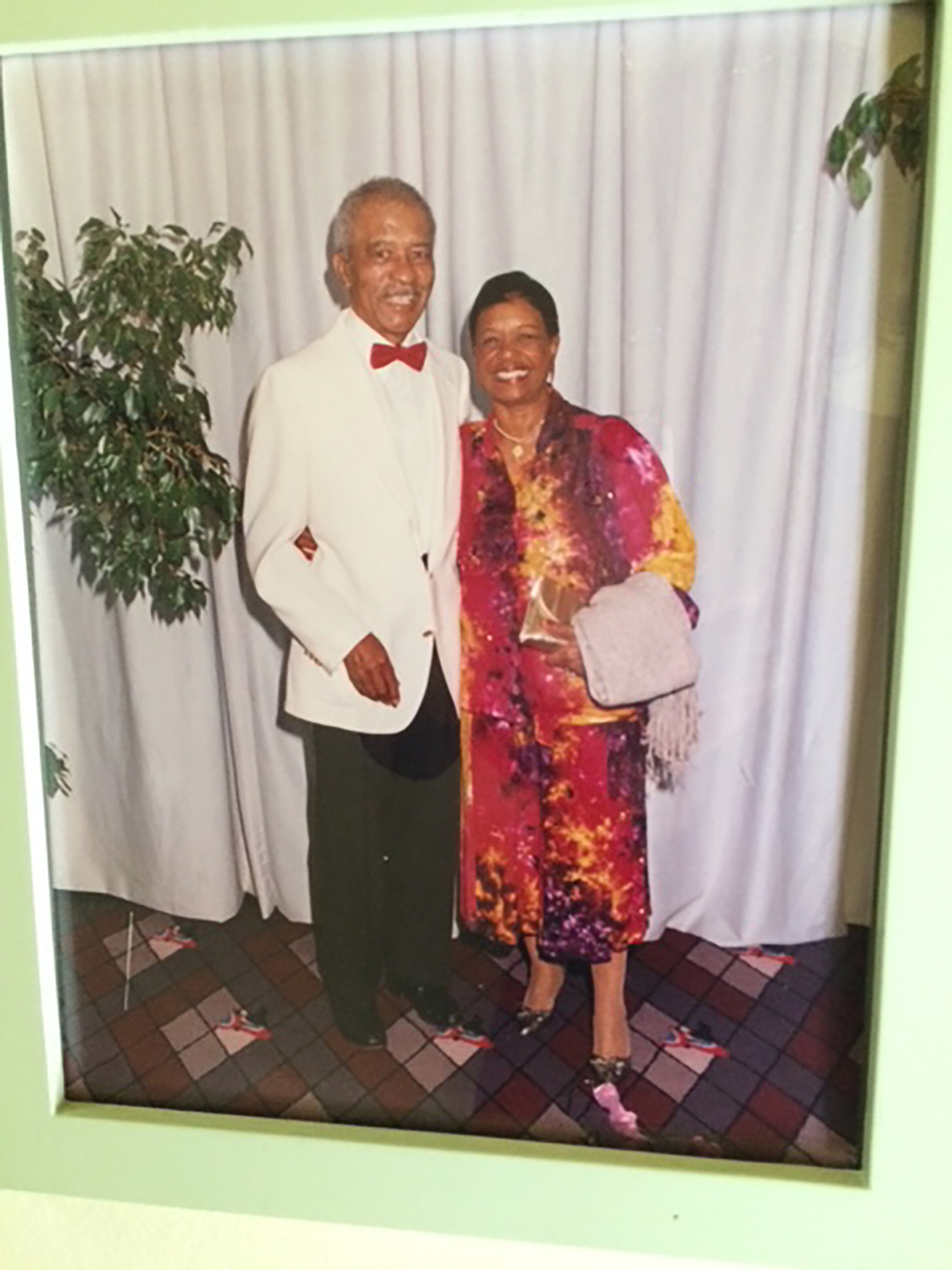

I also cherish my childhood memories in D.C. My parents purchased a home just two blocks from Takoma public park. It was there that I learned to play football, baseball, and most significantly, tennis. The tennis courts at Takoma public park bear my father’s name, Henry Kennedy Sr. He was affectionately known as “Mr. Tennis.”

To support his tennis-playing offspring, he dedicated himself to learning everything about the sport and became quite skilled as a coach and organizer of tennis tournaments. After his passing, community members successfully petitioned the city to honor him by naming the tennis courts after him.

Is it true that you were an excellent tennis player during your teenage years and faced Robert McNamara, the Secretary of Defense under President Lyndon Johnson?

I was a skilled junior tournament player, as was my brother. Together, we managed the tennis courts at the St. Albans Tennis Club in Washington, D.C. on the grounds of the National Cathedral.

On Sunday mornings, we were expected to close the courts during the Cathedral service, and typically we complied. However, there were moments when Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and National Security Adviser Walt Rostow would arrive and urge us to let them play. Occasionally, we even paired up with them in doubles matches.

On one occasion, a chauffeur came to the courts and informed us that the president was on the phone and wished to speak with McNamara immediately. The secretary stepped away for a few minutes, returned, and the game resumed.

Both McNamara and Rostow were quite competitive, but Rostow was the more skilled player of the two.

I read that tennis allowed you to attend the esteemed St. Albans School.

When my brother started overseeing the tennis courts at St. Albans, I would assist him. Whenever the courts were free and few people were around, I would practice alongside him.

The head professional at the club, who also served as the tennis coach at St. Albans School, observed me play and reached out to my parents to suggest I apply to the school. They immediately informed him that we didn’t have the financial means for St. Albans. He assured them he could secure a scholarship for me if I were accepted.

I ultimately applied, was accepted, and played as the No. 1 for the varsity team from eighth grade through to the 12th.

I’ve attended many excellent schools, but the most transformative experience was at St. Albans, where I came under the influence of my favorite teacher, John F. McCune, affectionately known to generations of boys as Gentleman Jack McCune. He was my American history instructor and introduced me to the writings of Richard Hofstadter at Columbia University and C. Vann Woodward at Yale University.

Engaging with their literature transformed my life. It was Mr. McCune who sparked my interest in the politics of historiography. He was a truly inspirational figure. We shared a birthday and developed a close friendship. I was by his side the day before he passed away and was privileged to speak at his memorial service at the National Cathedral.

“Anyone who categorizes me as conservative has not paid attention to my writings throughout my life.”

How did you develop an interest in law?

The concept of law was a significant part of my upbringing. My father frequently recounted the time he witnessed Thurgood Marshall argue the South Carolina whites-only primary case, Rice v. Elmore, back in 1947.

The case involved a Black business owner named George A. Elmore, who contested the exclusion of Black voters from the South Carolina Democratic primary. The ruling determined that the Democratic Party of South Carolina could no longer prevent qualified Black individuals from participating in primary elections.

My parents took great pride in their friendship with South Carolina’s prominent Civil Rights lawyer, Matthew J. Perry. However, the most substantial influence was the example set by my brother, a graduate of HLS in 1973, who became a prosecutor, a judge in Washington, D.C., and later a judge on the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. (Upon his retirement, he was succeeded by Ketanji Brown Jackson, who currently serves on the Supreme Court.)

You seem to hold a deep respect for your brother Henry.

Indeed, he was a dedicated jurist and is an incredibly supportive and affectionate older brother. He has been an excellent motivator for me and our younger sister, Angela, who is also a lawyer. His support has been especially crucial to me since my wife’s passing.

Can you share how you first met your spouse?

My relationship with Yvedt L. Matory commenced while I was a freshman at Yale Law School, with her being a second-year student at Yale Medical School. We had previously crossed paths when she was at Sidwell Friends School, just a short 15-minute stroll from St. Albans.

We tied the knot in June of 1985 and were blessed with three children. She served as a surgical oncologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Tragically, she succumbed to melanoma at just 48 years old, passing away two months before our 20th wedding anniversary. I have experienced a fortunate life, yet the sorrow that marked it was the loss of my beloved wife.

You worked as a clerk for Justice Thurgood Marshall during 1983-1984. Can you describe that experience?

It was exhilarating to collaborate with and assist “Mr. Civil Rights.” (By the way, two of my fellow clerks here are distinguished colleagues: Terry Fisher and Howell Jackson.)

A compelling case can be made for Marshall being the finest attorney in American history. Consider the range of positions he occupied — counsel for the NAACP, court of appeals judge, solicitor general, and Supreme Court justice — and the obstacles he triumphed over to contribute so positively to American society and jurisprudence!

I gained immense insights while working in the Marshall chambers. Observing him closely was an inspiration that has grown over time as I’ve developed a clearer understanding of the challenges he faced and the grace, determination, composure, and resilience he exhibited throughout his life.

Did your father have the opportunity to meet Marshall?

My father met Justice Marshall on the penultimate day of my clerkship. He conveyed to “Mr. Civil Rights” how motivating it was for him to witness Marshall fighting for the rights of Black individuals in a manner that commanded even grudging respect from his racist adversaries.

How did you find your way to Harvard Law School?

Upon leaving Yale Law School, I was prepared to start working for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund following my clerkships with Judge J. Skelly Wright and Justice Marshall.

However, towards the conclusion of my third year at law school, I received a phone call from HLS Dean James Vorenberg, who invited me to the Law School to discuss a career in legal education with him and other faculty members. I will forever appreciate his consideration.

When I express my affection for HLS, some acquaintances jest with me by calling me overly optimistic. What a pity! It’s difficult for me to envision a more ideal environment for a professor than Harvard Law School. For almost 40 years, I have been surrounded by remarkable colleagues and students. My time here has been a true blessing.

How do teaching, research, and writing compare in your career?

I take great pleasure in research and teaching and I am continuously writing. The course I have taught the most is contracts. For a long period, I experienced significant anxiety before each class. However, over the past decade, that anxiety has gradually lessened. Today, teaching contracts is entirely enjoyable. One of my upcoming publications will explore contracts within the context of close relationships — including friendship, dating, marriage, surrogacy, and adoption, among others.

The majority of my teaching and almost all of my writing have centered on the regulation of racial dynamics. I am on the verge of completing a book that I have been dedicated to for nearly a decade. It addresses this question: How did the protests challenging racial injustice during the mid-20th century alter American law? I endeavor to tackle this issue within more than 800 pages.

“I am profoundly troubled by the effective mobilization of racial animosity that has taken hold of American politics.”

You authored a book that delves into the historical, cultural, and social importance of one of the most contentious words in the English vocabulary. Could you elaborate on it?

This book is my sole best-seller and has sparked considerable debate. It led to an attempted disruption during a bookstore reading and has resulted in walkouts. Moreover, it has led attorneys to enlist my expertise as a witness in employment discrimination cases, union grievances, and criminal prosecutions, where I have acted as a witness for the defense in some situations and for the prosecution in others. The complete title of my book is “Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word.”

Many individuals asserted, “You could have chosen a different title for your book,” while others suggested, “You’re merely seeking to attract attention.” My primary aim was to enlighten, but how does one effectively educate? If your approach is dull, you won’t educate anyone. One must engage people and maintain their focus. Do I strive to do that? Absolutely, I do. But I don’t consider it a negative aspect.

Some media outlets have, at times, categorized you as conservative. How do you respond to that characterization?

Anyone who labels me as conservative has likely not paid attention to my writing throughout my career. I contend that the United States is plagued by unjust hierarchies and disparities that create unnecessary social distress. It is scandalous that in such a wealthy nation, many people lack security in basic necessities such as food, housing, healthcare, jobs, and personal safety against crime and inadequate policing. I advocate for reforms that proactively address these issues.

The intellectual and ideological circles that resonate with me predominantly find expression in publications like The American Prospect, Dissent, The Nation, and The London Review of Books. If that classification makes me conservative, then so be it.

Some onlookers have mistakenly categorized me as conservative because I appreciate the company of insightful conservatives like my recently departed friend and colleague Charles Fried, because I actively participate in events organized by conservative entities such as the Federalist Society, because I vocally critique specific policies like mandatory Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion statements for university hiring and advancement, and because I occasionally use certain rhetorical expressions that raise eyebrows — such as my usage of the word “negro,” a term I began employing in 1984 at the urging of my mentor Thurgood Marshall, and which I continue to use as a tribute to him and figures like A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, W.E.B. Du Bois, my grandmother Lillian Spann, “Big Momma,” and numerous other admirable individuals.

You indicated that your father held a pessimistic outlook regarding the potential for enduring racial justice in America. What is your perspective?

Indeed, my father was quite the pessimist regarding race issues. He did not hold the belief that we would triumph. The lineage he articulated is a notable one that encompasses figures such as Thomas Jefferson, Alexis de Tocqueville, Abraham Lincoln, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and Derrick Bell. Regrettably, there is much that supporters of this perspective can cite to reinforce their notion that racial justice in America is fated to fail.

Conversely, I find myself aligned with a different lineage, as articulated by Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr., a lineage that acknowledges the potential, indeed the probability, that racial integrity will increasingly emerge as a prominent and impactful aspect of American society.

I am genuinely perturbed by the effective rallying of racial animosity that has overtaken American politics. Paradoxically, I find some comfort in recognizing that a significant portion of this alarming backlash is a direct response to notable achievements in racial reform.

When I entered this world on September 10, 1954, my home state of South Carolina explicitly imposed a diminished, stigmatized position on African Americans. It was not an isolated case. Color-based hierarchies were widespread.

Nevertheless, within a single lifetime, due to the extraordinary struggles undertaken by Americans of all skin tones, circumstances shifted enough to allow a Black individual to ascend to the presidency of the United States — a graduate of Harvard Law School who conducted himself with utmost intelligence, elegance, and integrity.

Lastly, what guidance would you offer aspiring attorneys?

Maintain a high enjoyment factor by seeking out work that you are passionate about.