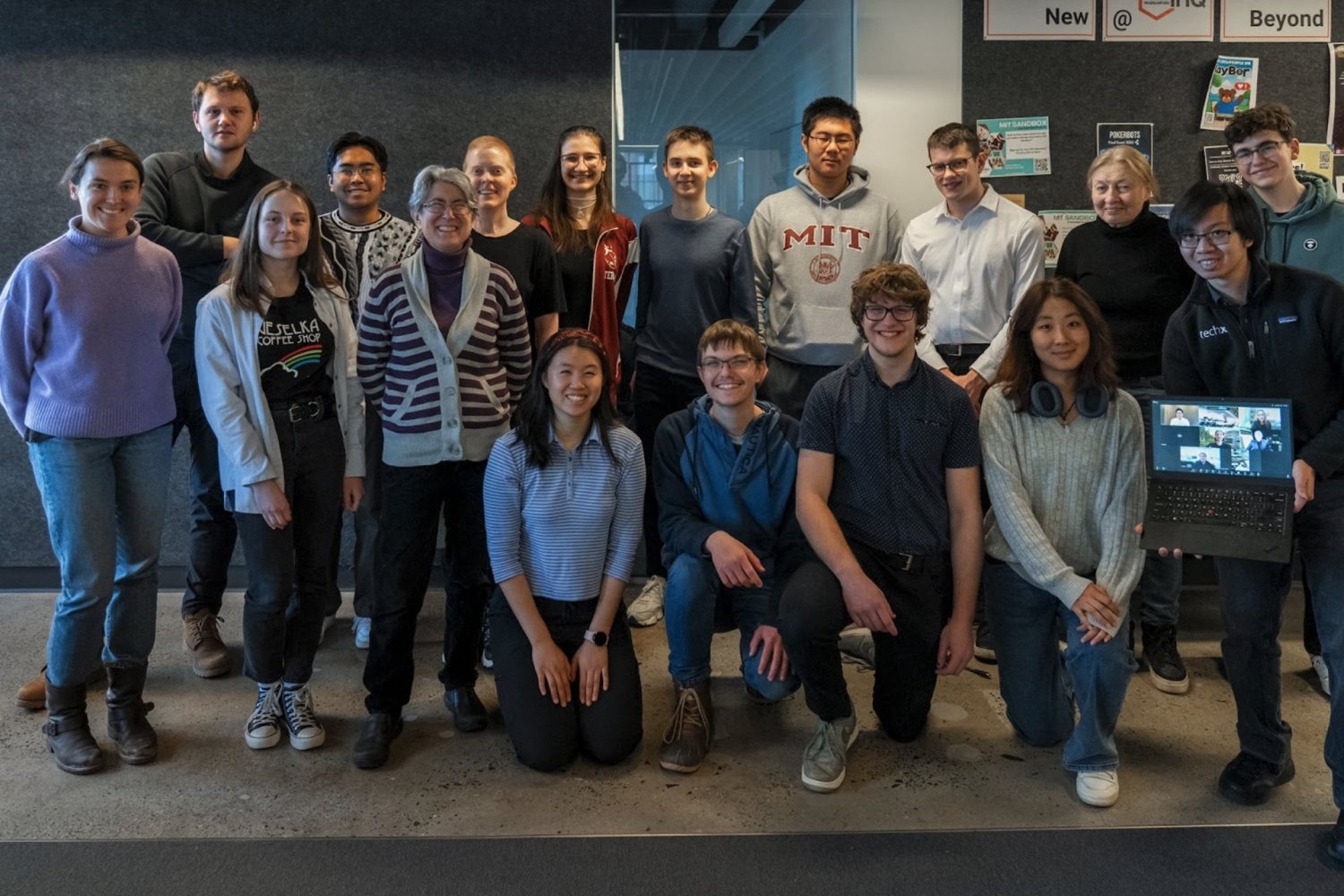

“No monetary rewards. However, our colleagues in Kiev are reaching out, and they’re likely to express gratitude,” was the slogan that attracted students and technology enthusiasts to participate in MIT-Ukraine’s inaugural hackathon this January.

The hackathon received support from MIT-Ukraine and Mission Innovation X, with contributions from MIT alumni globally. It was spearheaded by Hosea Siu ’14, SM ’15, PhD ’18, an experienced hackathon coordinator and AI researcher, working alongside Phil Tinn MCP ’16, a research engineer currently situated at SINTEF [Foundation for Industrial and Technical Research] in Norway. The initiative was crafted to emphasize real-world impact:

“In a conventional hackathon, you might endure a weekend of sleepless hours and some impressive yet primarily trivial prototypes. Here, we extended it over four weeks, and we anticipate genuine, significant results,” says Siu, the director of the hackathon.

One week of instruction, three weeks of project creation

In the initial week, participants engaged in lectures with prominent experts discussing critical issues that Ukraine faces today, covering topics ranging from mine contamination with Andrew Heafitz PhD ’05 to a presentation on misinformation by Nina Lutz SM ’21. Subsequently, participants formed teams to create projects aimed at tackling these obstacles, with guidance from leading MIT professionals like Phil Tinn (AI & defense), Svetlana Boriskina (energy resilience), and Gene Keselman (defense innovation and dual-use technology).

“I truly appreciated the robust framework they provided us — guiding us precisely through the current situation in Ukraine and potential remedies,” states Timur Gray, a freshman studying engineering at Olin College.

The final five projects encompassed demining, drone technology, AI and disinformation, education for Ukraine, and energy resilience.

Advancing demining initiatives

With existing technology, it is projected that it would require 757 years to completely de-mine Ukraine. Students Timur Gray and Misha Donchenko, a sophomore in mathematics at MIT, collaborated to investigate the latest advancements in demining technology and formulate strategies for how students could best support these innovations.

The team established connections with the Ukrainian Association of Humanitarian Demining and the HALO Trust to seek out opportunities for MIT students to directly assist demining efforts in Ukraine. They also contemplated project ideas to create tools for civilians to report mine locations, developing a demo webpage рішучість757, which features an interactive database mapping mine sites.

“Being able to leverage my skills for something that creates a real-world effect — that’s been the highlight of this hackathon,” asserts Donchenko.

Innovating drone manufacturing

Drone technology has emerged as one of Ukraine’s foremost advantages in combat — yet governmental red tape threatens to hinder innovation, as per Oleh Deineka, who chose this issue as the focal point of his hackathon project.

Participating remotely from Ukraine, where he studies post-war recovery at the Kyiv School of Economics, Deineka provided invaluable firsthand perspective from his experiences on the ground, enhancing the overall experience for all participants. Before the hackathon, he had already started developing UxS.AGENCY, a secure digital platform connecting drone developers with independent sponsors, aiming to ensure that the acceleration of innovations in drone technology is not stifled.

He pointed out that Ukrainian arms manufacturers have the ability to produce three times more weaponry and military equipment than the Ukrainian government can afford to procure. Stimulating the private sector’s development of drone production could mitigate this issue. The platform that Deineka is developing also seeks to minimize the risk of corruption by facilitating direct collaboration between developers and sponsors, avoiding bureaucratic hurdles.

Deineka is additionally collaborating with MIT’s Keselman, who delivered a presentation during the hackathon on dual-use technology — the concept that military advancements should also have civilian applications. Deineka highlighted that pursuing such dual-use technology in Ukraine could contribute not only to winning the war but also to establishing sustainable civilian uses, ensuring that Ukraine’s 10,000 trained drone pilots can find employment post-conflict. He indicated prospective applications such as drone-based urban infrastructure surveillance, precision farming, and even personal security — like a small drone accompanying a child with asthma, enabling parents to monitor their health in real-time.

“This hackathon has introduced me to MIT’s leading experts in innovation and security. Being invited to collaborate with Gene Keselman and others has been an extraordinary opportunity,” Deineka remarks.

Disinformation complexities on Wikipedia

Wikipedia has long served as a battlefield for Russian disinformation, from depicting artists like Kazimir Malevich to framing historical narratives. The hackathon’s disinformation group collaborated on a machine learning-based tool to identify biased edits.

They discovered that Wikipedia’s moderation system is vulnerable to perpetuating systemic bias, especially concerning history. Their project established a foundation for a potential student-led movement to monitor disinformation, suggest corrections, and develop tools for enhancing fact-checking on Wikipedia.

Education for Ukraine’s future

Russia’s assault on Ukraine has severely disrupted education, with incessant air raid alerts hindering classes, and over 2,000 Ukrainian schools either damaged or wrecked. The STEM education team concentrated on how they could assist Ukrainian students. They devised a plan for modifying MIT’s Beaver Works Summer Institute in STEM for students residing in Ukraine, or possibly for Ukrainians now displaced to surrounding nations.

“I hadn’t realized how many schools had been devastated and the profound effect that could have on children’s futures. You hear about the war, but this hackathon made it tangible in a way I hadn’t considered before,” says Catherine Tang, a senior in electrical engineering and computer science.

Vlad Duda, founder of Nomad AI, also contributed to the educational track of the hackathon focusing on language accessibility and learning assistance. One of the prototypes he showcased, MOVA, is a Chrome extension that utilizes AI to translate online materials into Ukrainian — an especially beneficial tool for high school students in Ukraine, who frequently lack the English language proficiency needed to engage with complex academic resources. Duda also created OpenBookLM, an AI-driven tool that supports students in converting notes into audio and custom study guides, akin to Google’s NotebookLM but intended to be open-source and adaptable to various languages and educational environments.

Energy resilience

The energy resilience team aimed to investigate affordable, more dependable heating and cooling technologies to reduce Ukrainian homes’ reliance on conventional energy networks vulnerable to Russian assaults.

The group examined polymer filaments that produce heat when stretched and cool down upon release, potentially providing low-cost, durable home heating solutions in Ukraine. Their focus was on determining the most effective braid configuration to enhance strength and efficiency.

From hackathon to implementation

Contrary to most hackathons, where projects conclude with the event, MIT-Ukraine’s objective is to assure that these concepts continue to progress. All projects developed during the hackathon will be evaluated as possible candidates for MIT’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) and MISTI Ukraine summer internship initiatives. Last year, 15 students engaged in UROP and MISTI projects related to Ukraine, contributing in sectors such as STEM education and reconstruction efforts. With the myriad of concepts generated during the hackathon, MIT-Ukraine is dedicated to broadening prospects for student-led projects and partnerships in the upcoming year.

“The MIT-Ukraine program emphasizes experiential learning, making an impact beyond MIT’s campus. The hackathon demonstrated that students, researchers, and professionals can unite to formulate solutions that matter — and the pressing challenges facing Ukraine necessitate nothing less,” asserts Elizabeth Wood, Ford International Professor of History at MIT and the faculty director of the MIT-Ukraine Program at the Center for International Studies.