Consider your most cherished possessions. In a progressively digital world, wouldn’t it be wonderful to preserve a replica of that beloved item along with all the memories it encapsulates?

Within mixed-reality environments, it’s possible to construct a digital counterpart of a tangible object, like an antique doll. However, replicating interactive aspects, such as its movements or the sounds it produces — the distinctive interactive qualities that originally set the toy apart — proves to be challenging.

Scientists from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) aimed to address this issue and they have developed a promising answer. Their “InteRecon” initiative allows individuals to re-capture physical items through a mobile application and subsequently animate them within mixed-reality contexts.

This prototype could recreate the interactive functions found in the physical realm, such as the head movements of your favorite bobblehead, or simulating a classic video on a digital version of your retro television. It fosters more realistic and personal digital environments while preserving cherished memories.

InteRecon’s capability to reconstruct the interactive experiences of various items can make it a beneficial resource for educators illustrating vital concepts, like showcasing how gravity affects an object. Additionally, it could introduce a fresh visual dimension to museum displays, such as animating a piece of art or reviving a historical mannequin (without the frights associated with characters from “Night at the Museum”). In the long run, InteRecon might assist in teaching a medical apprentice procedures like organ surgery or cosmetics by illustrating each movement necessary to accomplish the task.

The remarkable potential of InteRecon lies in its ability to infuse movements or interactive functionalities into countless objects, as noted by CSAIL visiting researcher Zisu Li, the principal author of a study introducing the technology.

“Although capturing a photo or video is an excellent means to preserve a memory, those digital representations are fixed,” mentions Li, who is also a PhD candidate at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. “Our research indicated that users desired to reconstruct personal belongings while maintaining their interactivity to enhance their memories. With the capabilities of mixed reality, InteRecon can help these memories endure longer in digital environments as interactive virtual items.”

Li and her team are set to showcase InteRecon at the 2025 ACM CHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Enhancing the realism of a virtual world

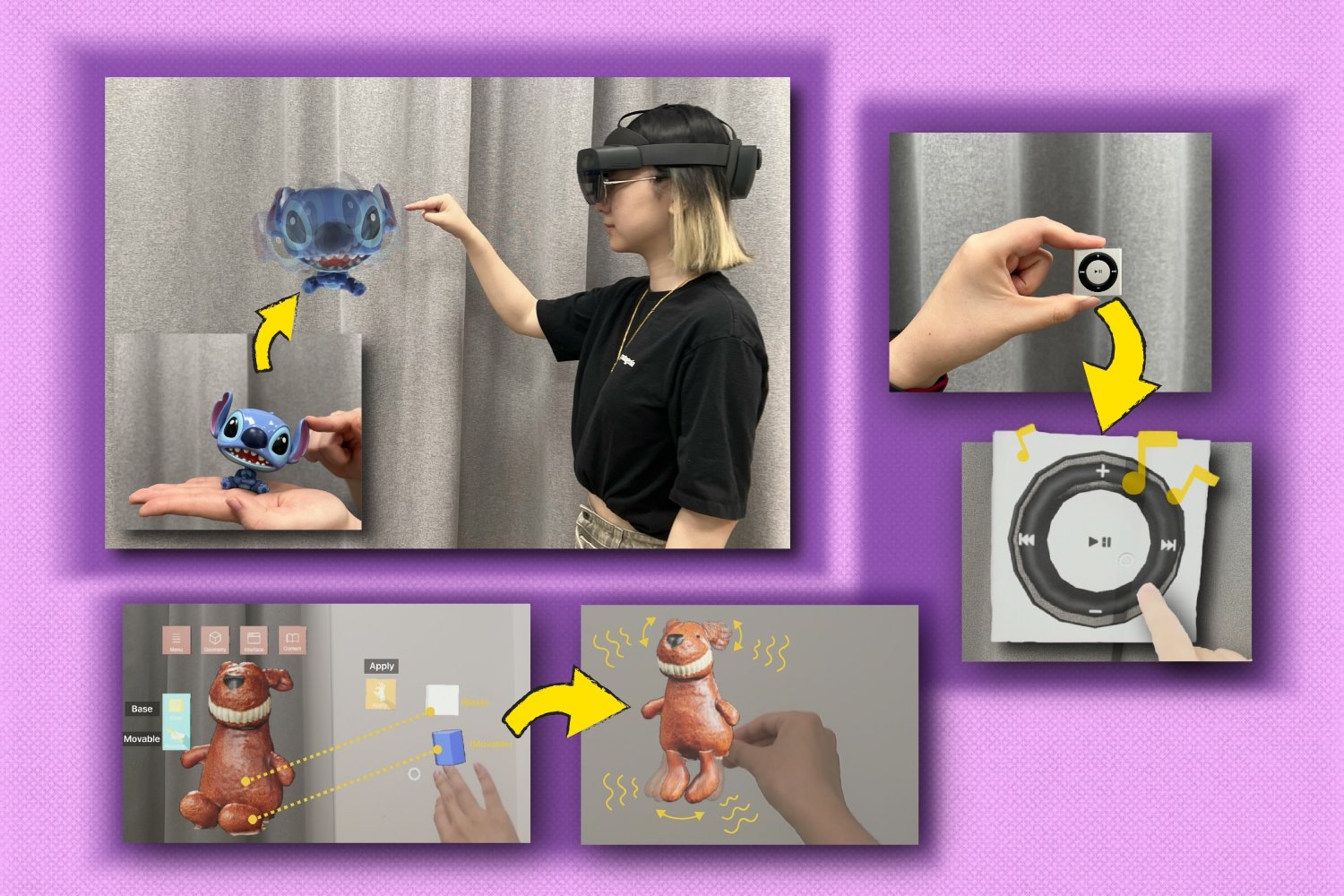

To enable digital interactivity, the team initially created an iPhone application. Users scan the item completely from all angles three times to guarantee thorough capture. The 3D model can then be imported into the InteRecon mixed reality platform, where you can designate (“segment”) specific regions to determine which aspects of the model will possess interactivity (such as the arms, head, torso, and legs of a doll). Alternatively, the automated segmentation feature of InteRecon can be utilized.

The InteRecon interface can be accessed through a mixed reality headset (like Hololens 2 and Quest). This platform allows you to select a programmable action for the part of the item you wish to animate following the segmentation of your model.

Movement choices are displayed as motion demonstrations, permitting you to experiment before settling on one — for instance, a floppy motion that mimics the way a bunny doll’s ears sway. You can also pinch an individual part and test out various methods to animate it, like sliding, dangling, or swinging like a pendulum.

Your vintage iPod, digitally rendered

The team demonstrated that InteRecon can also replicate the interface of physical electronic devices, such as a nostalgic television. After generating a digital copy of the object, you can personalize the 3D model with different interfaces.

Participants can explore example widgets from various interfaces before selecting a movement: a screen (either a TV display or a camera’s viewfinder), a rotating knob (for adjusting volume), an “on/off” switch, and a slider (for modifying settings on something akin to a DJ booth).

Li and her colleagues introduced an application that rebuilds the interactivity of a vintage television by combining virtual widgets like an “on/off” switch, a screen, and a channel selector on a TV model, and integrating old videos into it. This transformation breathes life into the television model. Furthermore, you can upload MP3 files and add a “play button” to a 3D model of an iPod to experience your favorite tunes in a mixed reality setting.

The researchers believe InteRecon opens up fascinating new pathways in crafting lifelike virtual environments. A user study validated that individuals from varied disciplines share this excitement, perceiving it as user-friendly and versatile in showcasing the richness of users’ memories.

“One aspect I particularly value is that the items users recall are not perfect,” states Faraz Faruqi SM ’22, another author of the study who is also a CSAIL affiliate and MIT PhD student in electrical engineering and computer science. “InteRecon embraces those imperfections in mixed reality, accurately reproducing what made a personal item like a teddy bear with a few buttons missing so significant.”

In a related inquiry, users envisioned how this innovation could be utilized in professional contexts, from educating medical students on surgical procedures to aiding travelers and researchers document their journeys, and even assisting fashion designers in testing materials.

Before InteRecon is implemented in more sophisticated scenarios, however, the team aims to refine their physical simulation engine to achieve greater accuracy. This enhancement would facilitate applications like aiding a medical apprentice in mastering the precise skills required for specific surgical movements.

Li and Faruqi may also integrate large language models and generative algorithms that can recreate lost personal items into 3D representations through verbal descriptions, in addition to elucidating the functionalities of the interface.

Regarding the next steps for the researchers, Li is pursuing a more automated and robust pipeline capable of creating interactivity-preserved digital twins of larger physical realms in mixed reality for end users, such as a virtual workspace. Faruqi intends to develop a technique that can tangibly recreate lost items using 3D printers.

“InteRecon signifies a thrilling new horizon in the realm of mixed reality, extending beyond simple visual replication to grasp the unique interactivity of physical objects,” asserts Hanwang Zhang, an associate professor at Nanyang Technological University’s College of Computing and Data Science, who was not involved in the study. “This technology holds the potential to transform education, healthcare, and cultural exhibitions by introducing a new level of immersion and personal connection within virtual environments.”

Li and Faruqi collaborated on the paper with Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) master’s student Jiawei Li, PhD student Shumeng Zhang, Associate Professor Xiaojuan Ma, and assistant professors Mingming Fan and Chen Liang from HKUST; ETH Zurich PhD student Zeyu Xiong; and Stefanie Mueller, the TIBCO Career Development Associate Professor in the MIT departments of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and Mechanical Engineering, as well as the leader of the HCI Engineering Group. Their research received support from the APEX Lab of The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou) in partnership with the HCI Engineering Group.