Two years prior, MIT literary professor Arthur Bahr experienced one of the finest days of his existence. While sitting within the confines of the British Library, he had the privilege to examine the Pearl-Manuscript, a unique bound tome from the 1300s that encompasses the earliest iterations of the remarkable medieval poem “Pearl,” the renowned narrative “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” along with two additional poems.

Currently, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” is frequently studied within high school English curricula. Nevertheless, it likely would have been forgotten by history had the Pearl-Manuscript not been preserved, similar to the other literary works in this particular collection. As it stands, the identity of the authors of these writings remains a mystery. However, one fact is undeniable: the surviving manuscript is an intricately designed volume, featuring custom illustrations and adept craftsmanship with parchment. This book represents its own artistic creation.

“The Pearl-Manuscript is just as remarkable and distinctive and surprising as the poems it houses,” Bahr remarks about the document, formally known as “British Library MS Cotton Nero A X/2.”

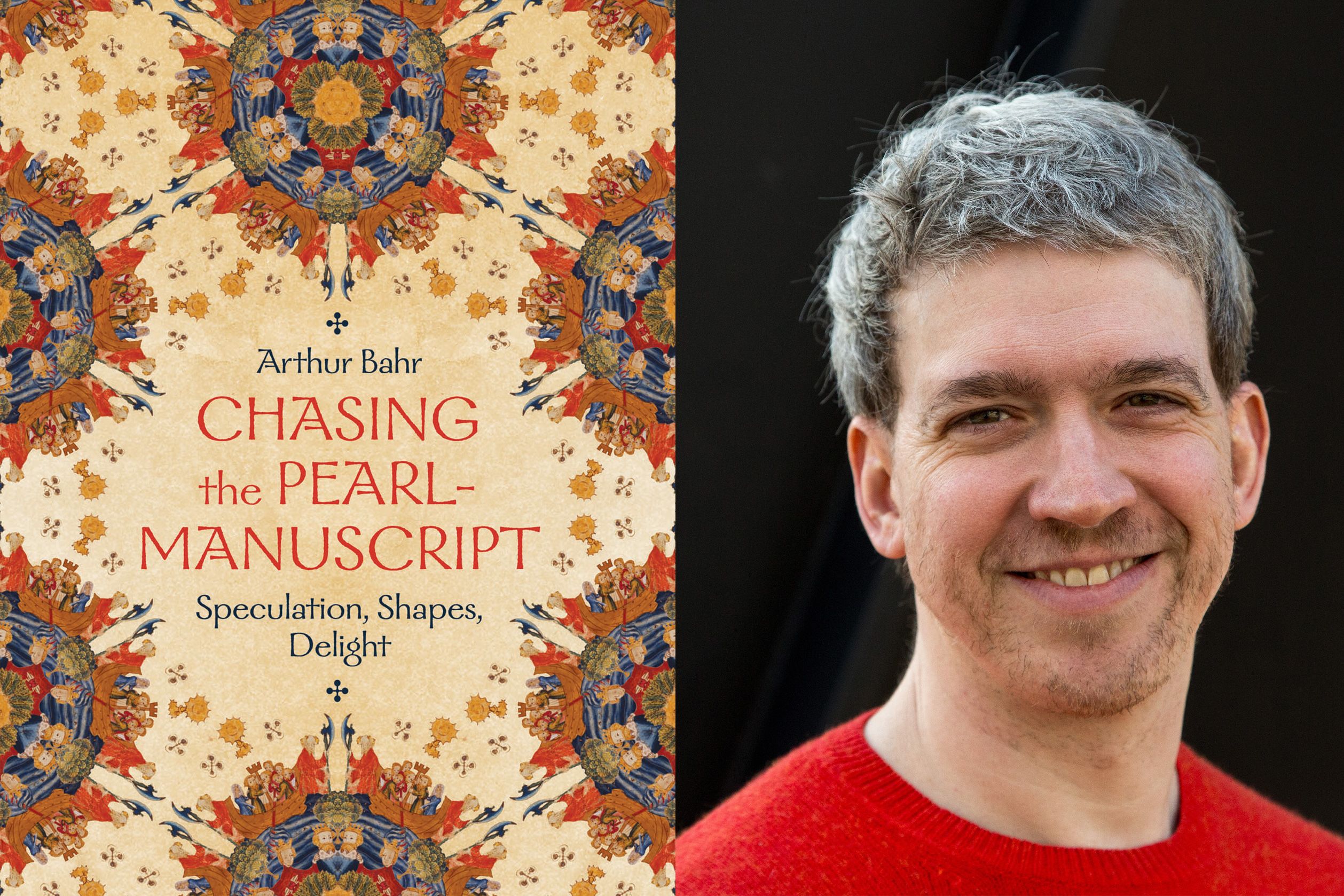

Bahr delves into these concepts in his latest publication, “Chasing the Pearl-Manuscript: Speculation, Shapes, Delight,” released this month by the University of Chicago Press. In this work, Bahr merges his extensive understanding of the text within the volume with meticulous analysis of its tangible properties — aided by technologies such as spectroscopy, which has disclosed some secrets of the manuscript, along with the traditional examination Bahr conducted in person.

“My contention is that this physical artifact amounts to more than merely its individual components, through the creative interaction of text, image, and materials,” Bahr states. “It forms a cohesive volume that mirrors the themes of the poems themselves. Most manuscripts are assembled in practical ways, but this one stands apart.”

Ode to the most exquisite poem

Bahr first stumbled upon “Pearl” while an undergraduate at Amherst College, during a class led by medieval scholar Howell D. Chickering. The poem provides a complex exploration of Christian morality; a father, mourning the loss of his daughter, dreams he is conversing with her about the essence of life.

“It is the most exquisite poem I have ever encountered,” Bahr comments. “It astounded me, due to its formal sophistication, and for the genuinely touching human narrative.” He adds: “In some ways, this is the reason I am drawn to medieval studies.”

Considering that Bahr’s initial book, “Fragments and Assemblages,” investigates how medieval bound texts were frequently compilations of diverse documents, it was a natural progression for him to apply this analytical framework to the Pearl manuscript as well.

Most academics believe the Pearl manuscript has a singular author — although certainty eludes us. Following “Pearl,” the manuscript presents two additional poems, “Cleanness” and “Patience.” Concluding the collection, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” depicts a haunting, surreal narrative of bravery and chivalry set in the (possibly mythical) court of King Arthur.

In the book, Bahr identifies thematic connections among the four texts, scrutinizing the “connective tissue” that allows the “manuscript to begin to integrate into a crafted, imperfect, temporally layered entity,” as he articulates. Some of these connections are broad, encompassing recurring “challenges to our speculative faculties”; the works are replete with apparent contradictions and dreamlike landscapes that test the reader’s interpretive abilities.

There are other indications of alignment within the texts. “Pearl” and “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” each contain 101 stanzas. The texts exhibit numerically cohesive structures, with “Pearl” centered around the number 12. Almost every stanza comprises 12 lines (Bahr suspects this deviation is deliberate, akin to a finely crafted rug possessing an intentional flaw, which may apply to the “extra” 101st stanza). Each page contains 36 lines. Upon examining the manuscript physically, Bahr noted 48 instances with decorated initials, though the identity of the creators remains unknown.

“The more you examine, the more you uncover,” Bahr remarks.

Materiality is significant

Some of our insights into the Pearl-Manuscript are quite recent: Spectroscopy has unveiled that the volume initially featured simple line drawings, which were subsequently enhanced with colored ink.

However, nothing can replace the experience of reading physical books. This necessity took Bahr to London in 2023, where he received an extended opportunity to study the Pearl-Manuscript up close. Far from being a mere formality, this visit provided Bahr with fresh perspectives.

For example, the Pearl-Manuscript is inscribed on parchment, which originates from animal skin. At a pivotal moment in the “Patience” poem, a reimagining of the Jonah and the whale narrative, the parchment has been reversed so that the “hair” side of the material faces upward, instead of the “flesh” side; this is the only occurrence of such in the manuscript.

“As you read about Jonah being consumed by the whale, you can sense the hair follicles where you would not anticipate,” Bahr comments. “At the exact moment when the poem thematizes an unnatural inversion of inside and outside, you are experiencing the opposite side of a different creature.”

He further states: “The act of physically handling the Pearl-Manuscript fundamentally altered my understanding of how this poem would have resonated with medieval readers.” In this context, he asserts, “Materiality is crucial. Screens are empowering, and without the digital facsimile I could not have authored this book, but they can never replace the original. The chapter on ‘Patience’ emphasizes that.”

Ultimately, Bahr believes that the Pearl-Manuscript supports his argument presented in “Fragments and Assemblages,” that the medieval reading encounter was often intertwined with the physical construction of volumes.

“My stance in ‘Fragments and Assemblages’ was that medieval readers and book makers engaged seriously and often astutely with how the material assembly and selection of texts into a physical entity made an impact — mattered — and held the potential to modify the interpretations of the texts,” he explains.

A commendable contribution to the group project

“Chasing the Pearl-Manuscript” has garnered accolades from fellow academics. Jessica Brantley, professor and chair of the English Department at Yale University, remarked that Bahr “proposes an adventurous multilayered interpretation of both text and book and offers a significant re-evaluation of the codex and its poems.”

Daniel Wakelin from Oxford University stated that Bahr “provides an authoritative reading of these poems” and presents “a bold model for examining material texts and literary works together.”

For his part, Bahr aspires to engage a wide range of readers, much like his medieval literature classes attract students with diverse intellectual pursuits. In the process of creating his book, Bahr also acknowledges two MIT students, Kelsey Glover and Madison Sneve, who contributed to the project through the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP), focusing on the illustrations and unique manuscript markings, among other aspects.

“It’s a quintessentially MIT poem, in that the author, or authors, are not just consumed with mathematics, geometry, numbers, and proportions, they are equally obsessed with artifact construction, architectural nuances, and physical craftsmanship,” Bahr notes. “There’s a distinctly ‘mens et manus’ spirit in the poems that mirrors the manuscript,” he continues, alluding to MIT’s motto, “mind and hand.” “I believe this helps elucidate why these remarkable MIT students were invaluable in my research.”