For the past seven years, a CT scanner has been continuously operating almost around the clock, nestled within a laboratory at the University of Michigan Research Museums Center.

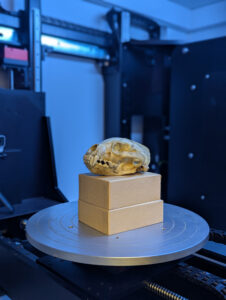

Within the device, researchers examine animal specimens: snakes, lizards, frogs, bats, rodents, wasps, fish, an entire red fox, an armadillo. This microCT scanner directs concentrated X-rays towards the specimens, which are secured to a metallic plate. The metallic plate rotates during the scanning process, with the X-rays reflecting off the specimen, captured by a sensor that converts the light waves into anatomical slices of the specimen.

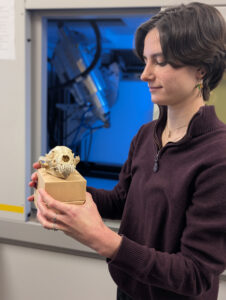

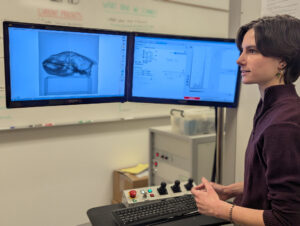

Lab technician Haley Martens, having calibrated a computer application that dictates the level of detail in the images, reconstructs the anatomical slices into 3D images exhibiting the animal’s nervous system, skeletal framework, circulatory structure, or any specific aspect the researchers wish to investigate. The apparatus can image even the tiniest components of an animal while preserving the integrity of the specimen itself.

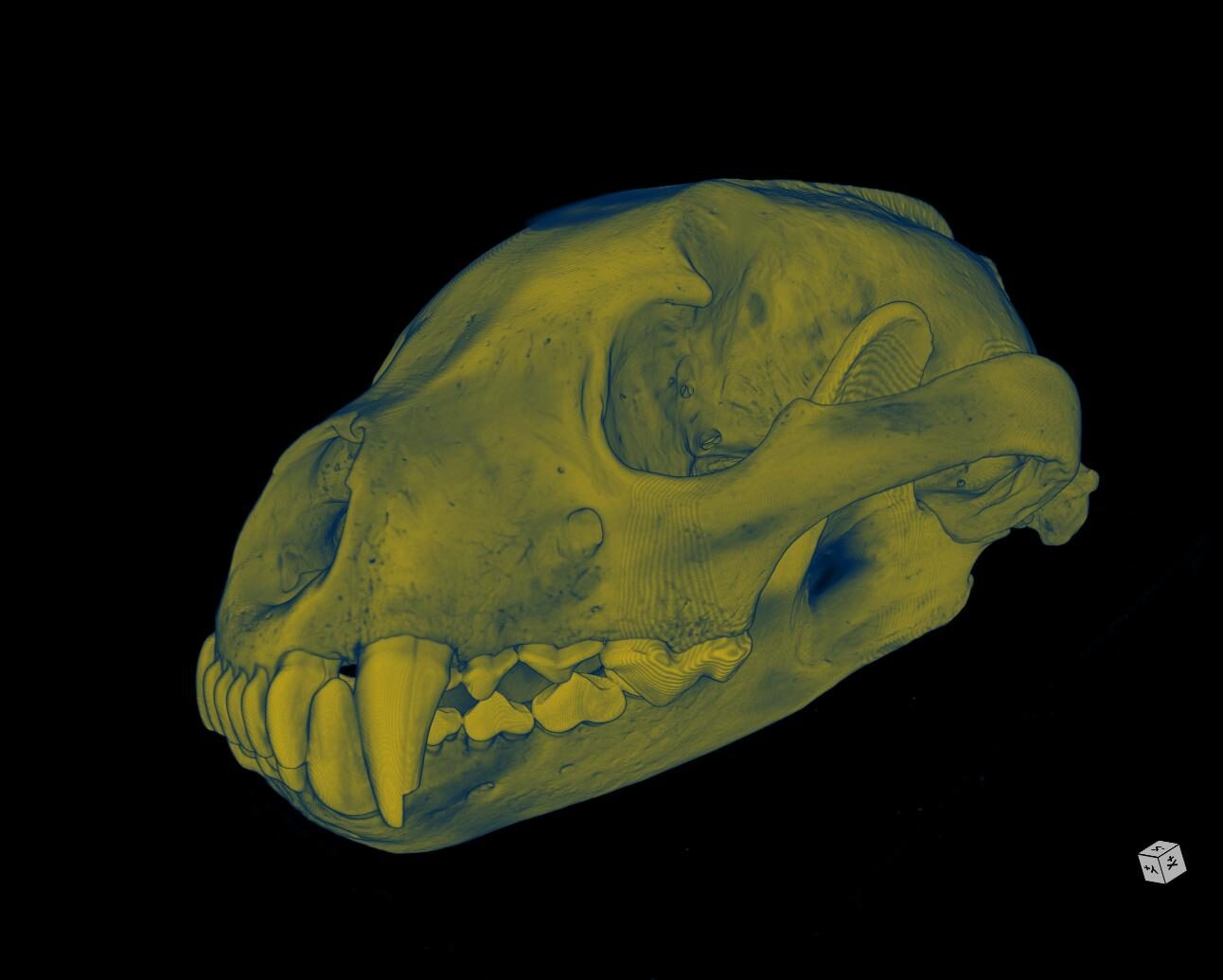

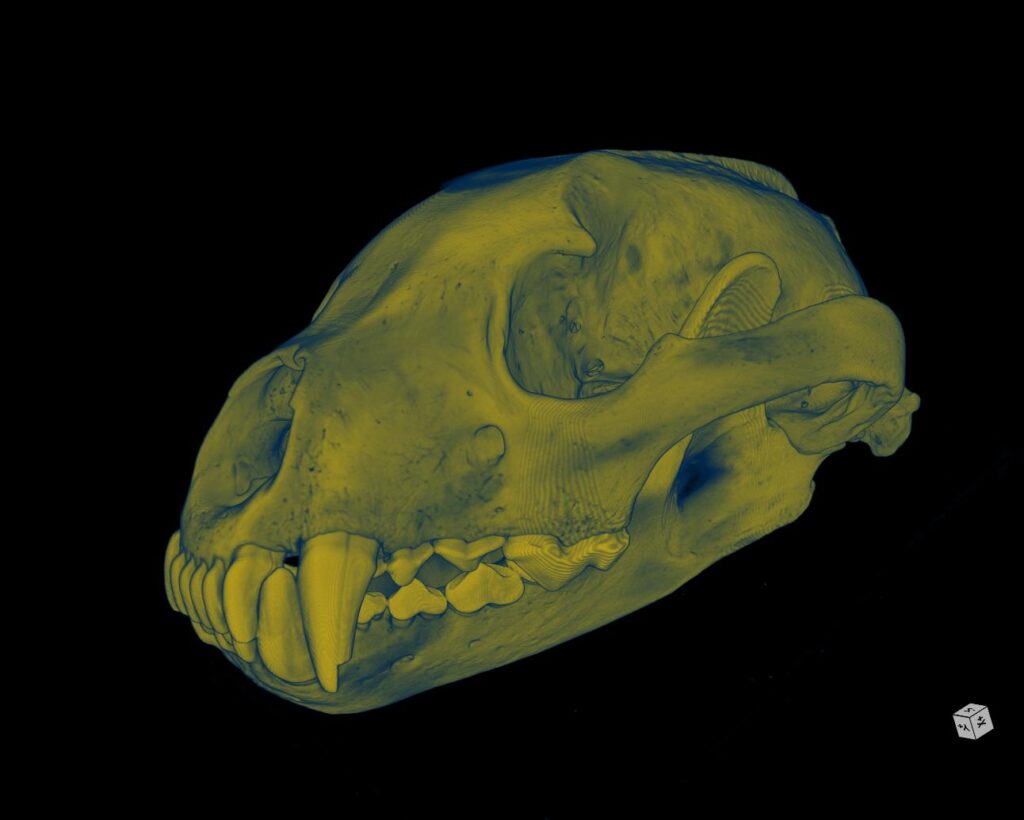

Recently, the U-M MicroCT Scanning Laboratory marked the completion of its 10,000th scan: a 3D image of a wolverine skull collected in British Columbia in 1948. This skull is included in the U-M Museum of Zoology’s specimen collection, located at the Research Museums Center, a U-M facility off-campus that houses over 20 million specimens across four museums.

“In the realm of museums, a principal goal is the preservation of these specimens for enduring care, extended research indefinitely for purposes that may be hard to forecast,” stated lab manager Ramon Nagesan. “The MicroCT Lab has proven to be a remarkable resource, allowing us to explore these specimens in depth without risking harm or destruction.”

“We can effectively create a comprehensive visualization of the anatomy of the organisms we scan, including everything from skeletal arrangements to neural tissue, and, crucially, we can accomplish this without damaging or destroying the specimens. This 10,000th scan is significant for us, as it signifies achieving a substantial milestone in terms of the data we’ve accumulated.”

Equally important, a considerable portion of this data is accessible for researchers beyond the U-M community, as noted by Nagesan. Each scan that is carried out is uploaded to the lab’s online database, enabling researchers to request CT scans or even STL files for creating 3D printed representations of the specimens.

Detailed data

Similar to a CT scanner found in medical facilities, the microCT scanner employs X-rays to capture images of bones, muscles, and other soft tissues. However, the microCT scanner provides significantly higher resolution images. “Micro” refers to the detail of the scans: a microCT scan ranges from approximately one micron (a strand of spider silk measures roughly three to eight microns) to about 150 microns, as explained by Nagesan. In contrast, a standard medical CT scanner typically operates at around 650 microns. The smaller the measurement, the greater the resolution, he elaborated.

During the scanning of the wolverine skull, or other skeletal scans, the microCT scanner captures 1,600 images of the skull. For scans requiring more detail, such as examining fluid specimens that are dyed to highlight soft tissue, high-density scans like fossils, or low-density specimens such as flora, the scanner will capture more images and require additional time within the scanning apparatus, according to Martens.

Depending on the level of detail and the preparation of the specimen, the scanner can create anatomical images of the specimen’s skeleton or exoskeleton, musculature, nervous system, circulatory system, or even the contents of its stomach, regardless of the specimen’s age.

“Experiencing work in the CT lab is a remarkable educational opportunity, as I continuously acquire insights regarding the species I am scanning, along with the technology I utilize…”

“Every week introduces fresh and thrilling challenges, ranging from examining cordyceps fungus inside insects to assessing large reticulated pythons, Roman glass artifacts, and even living foliage,” Martens stated. “As CT scanning gains traction and significance within our domain, I consider myself fortunate to partake in exhilarating new studies, such as identifying dietary components in serpents and exploring the brains of wasps.”

Although this 10,000th scan signifies merely a minuscule portion of the 22 million objects housed at the Research Museums Center, this total encompasses at least one example from each vertebrate genus included in a program known as the Open Vertebrate Thematic Collections Network, or oVert, as mentioned by Nagesan. This initiative, supported by the National Science Foundation, sought to create CT images of approximately 20,000 specimens preserved in fluid from U.S. museum collections. With that endeavor concluded in 2022, lab personnel are now scanning based on proposals submitted to the laboratory.

Capturing history for the future

As the scanning of the wolverine skull occurred, two undergraduate scholars transported carts filled with garter snakes towards the Museum of Zoology’s collections for cataloging, a donation from a U-M graduate whose career revolved around the species. While the most ancient specimen in the Museum of Zoology has been part of the collection for nearly two hundred years, new specimens continually enter the collections, whether through donations or original investigations, as noted by Hernán López-Fernández, the director of the Museum of Zoology.

“We are striving to expand because essentially, our capability to learn from the past and understand the alterations in biodiversity moving forward necessitates that we persist in documenting what biodiversity resembles today,” he explained. “It is vitally important that our collections continue to grow, and we pursue this very judiciously, meticulously, and thoughtfully.”

Every specimen holds a treasure trove of insights into the animal’s life, López-Fernández indicated. With innovative technologies such as microCT scanning and genomic-level sequencing of specimens, researchers are able to examine a 150-year-old sample to explore not only its skeletal structure but also its dietary habits, growth patterns, and habitat.

“A fish or snake collected from a location that no longer exists—transformed now into a parking lot, apartment complex, or shopping mall—enables us to delve into their biology,” López-Fernández stated.

“Maintaining this historical collection is proving increasingly essential to comprehend the shifts our planet is undergoing—amidst environmental changes of all types: global warming alongside the metamorphosis of ecosystems into urban or semi-urban regions. Frequently, the sole evidence we possess of how a particular segment of the earth appeared resides within our collections.”