“`html

David Y. Yang.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Nation & World

When global commerce transcends monetary value

Economist’s innovative tool examines how China surpasses the U.S. in leveraging political influence through import and export regulation

Global trade offers far more than mere imports and exports. According to David Y. Yang, Yvonne P. L. Lui Professor of Economics, trade can serve as a means to exert political influence.

Yang observed as China enacted trade limitations on competitor Taiwan following a 2022 visit to the island by U.S. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. A decade earlier, the apprehension of a Chinese fishing boat captain in disputed waters culminated in Beijing ceasing exports to Japan of specific rare earth minerals, which are vital components for wind turbines and electric vehicles.

“Another instance is China prohibiting the import of Norwegian salmon for nearly ten years as retribution for awarding a Nobel Prize to the dissident Liu Xiaobo,” stated Yang, a political economist with authority on the East Asian powerhouse.

His recent working document, co-authored with Princeton’s Ernest Liu, introduces a framework for assessing how much geopolitical leverage a nation can exert by threatening trade interruptions. Presently, the economists discover, China holds considerable sway over trading partners while the United States possesses less influence than anticipated relative to its economic stature.

“With the emergence of new data sources and analytical tools, this is something we can now examine very thoroughly,” Yang underscored. “Conducting these objective, data-driven assessments feels even more imperative in the current global geopolitical landscape.”

Their model specifically evaluates a series of predictions put forth by mid-20th-century Harvard professor Albert O. Hirschman, a German-born Jew who escaped Europe during World War II. His publication “National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade” (1945) provided a theoretical perspective on how nations might utilize trade to assert geopolitical dominance.

“Hirschman approached the topic optimistically,” Yang remarked. “Instead of engaging in military confrontations, nations could resort to economic wars to achieve similar objectives.”

Hirschman recognized that trade imbalances could be manipulated. However, deficits and surpluses weren’t the sole significant factors. Additionally crucial was the importance and replaceability of the goods in question. Stopping the supply of crude oil tends to have a much greater impact than withholding textile shipments.

“If one nation becomes excessively dependent on another, it might be economically sensible,” Yang clarified. “Yet it can render the first nation vulnerable by subjecting it to adverse power relationships.”

Hirschman’s concepts appeared less applicable in the post-war era, with the widespread inclination for enhanced free trade. However, the book feels relevant again today, commented Yang, who recently included it in an undergraduate economics course.

“I instructed students to read the initial chapters and speculate on when it was authored,” he remembered. “Many assumed it was penned last year.”

Yang and Liu began formalizing Hirschman’s vision nearly three years ago, well before the ongoing series of assertive U.S. tariffs. “Many of the anecdotal instances that inspired our research originated from China,” Yang stated.

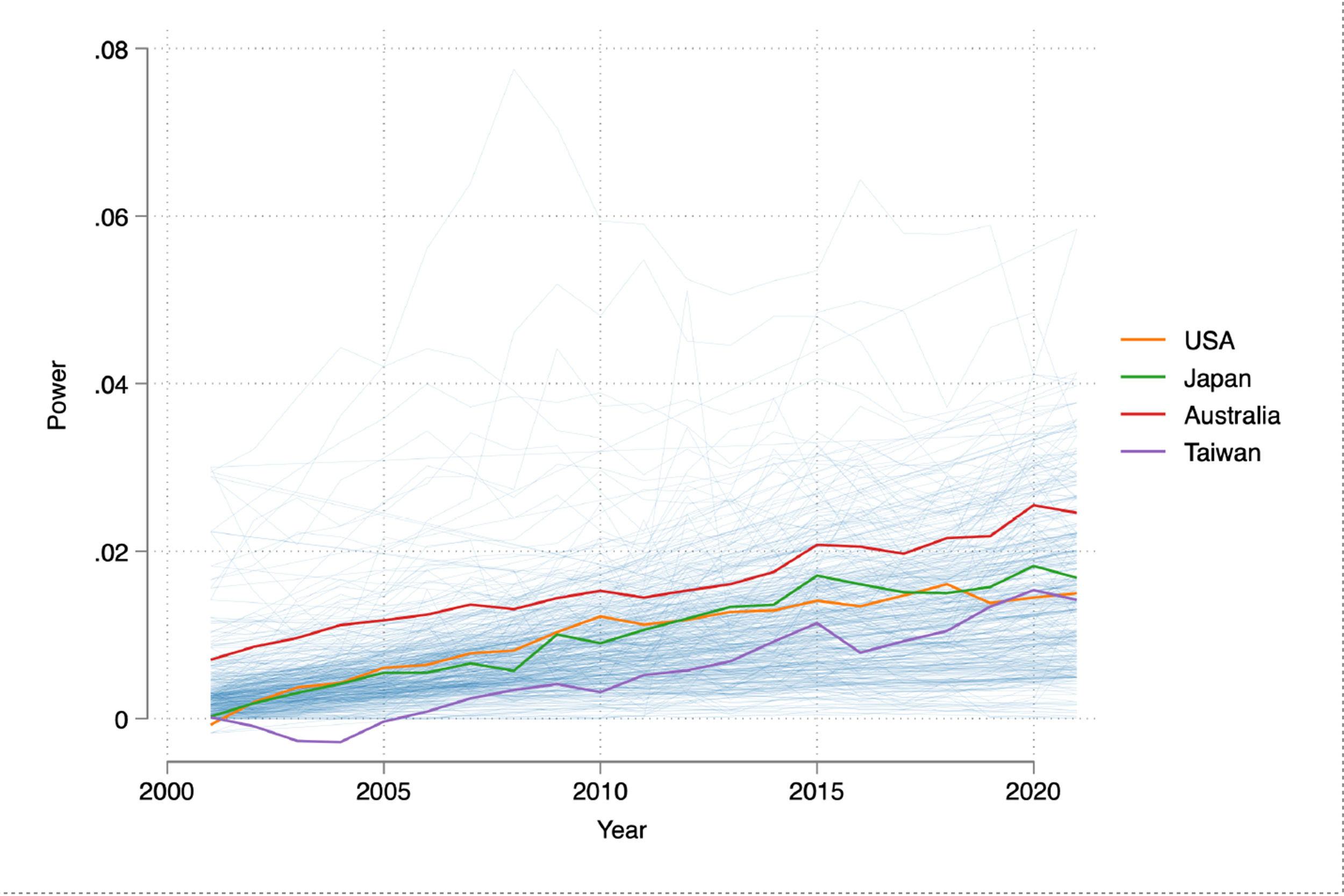

Indeed, their model illustrates China’s trade influence increasing over the previous two decades as it transformed crucial industries into political tools. Chemical products, medical supplies, and electrical devices emerged as especially powerful. The nation’s trade leverage proved larger than expected considering the scale of its GDP, second only to the world’s largest economy by many trillions of dollars.

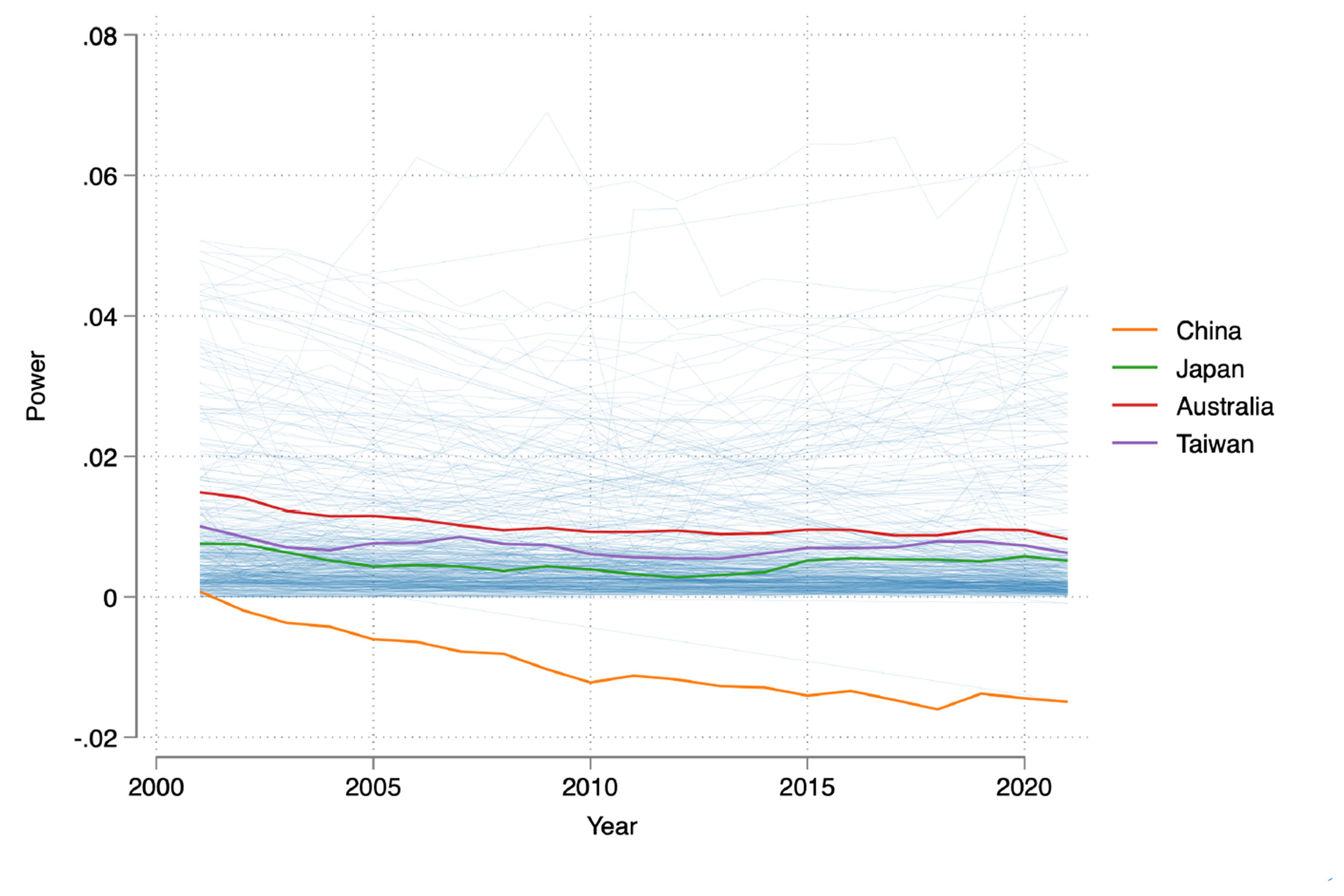

U.S. trading influence over China diminishes

This graphic illustrates the directed power (across all sectors) between the U.S. and a country each year.

Credit: Ernest Liu and David Y. Yang

“In the early 2000s, the U.S. possessed more absolute authority over China through trade disruptions,” Yang pointed out, stating that the data on the U.S. remained relatively stable throughout the two-decade span they investigated.

“However, circumstances have swiftly shifted,” he added. “China currently wields more trade power over the U.S. and, at this moment, can exert positive influence over any other entity globally.”

China’s trade influence on the upswing

This graphic depicts the directed power (in all sectors) between China and a country for each year.

“`r.

Attribution: Ernest Liu and David Y. Yang

Yang and Liu also examined a set of hypotheses regarding the ramifications of uneven power distribution. Initially, the economists utilized a repository containing millions of incidents involving the governments of two commercial partners, validating that talks and other kinds of interaction grow with the imbalances identified by Hirschman.

An additional dataset, derived from global opinion surveys, was employed to assess bilateral geopolitical alignment over time and to validate a second anticipated outcome. Yang and Liu discovered that national leaders were organizing efforts to enhance and secure trade dominance — by restricting imports, for instance — when relations with a trade partner soured due to political changes.

“Although many instances we present in our study originate from China, we aim to demonstrate that this is a broader occurrence,” Yang stated. “Trade represents a source of influence accessible to any nation.”

The article is interwoven with further observations.

“If the European Union functioned as a single entity, it could effectively wield positive influence over China,” Yang remarked. “However, individual EU nations possess negative power over China. I believe it’s not a coincidence that China often engages with EU members on a bilateral basis.”

Moreover, the U.S. and China exhibit weaknesses against one another. The paper includes a pair of maps depicting their trade power in relation to the rest of the globe from 2001 to 2021. American strength seems to peak in North America, while China’s is rooted in the Asia Pacific area.

“Concerning global power dynamics,” Yang noted, “medium-sized nations are predominantly the ones that face aggression.”

The findings highlight a recent transformation in the international trade landscape. For half a century following World War II, Yang mentioned, the largest economies engaged in imports and exports with the aim of optimizing efficiency for the advantage of domestic enterprises and consumers.

“What’s alarming is that we are beginning to observe the reverse,” he indicated. “Trade is being reorganized to factor in power dynamics. However, unlike the positive-sum nature of efficiency-boosting trade where countries produce based on their comparative advantages, power dynamics in trade result in negative-sum outcomes, damaging welfare for both parties.”

“As we gradually come to terms with it,” Yang added, “it might not be geopolitically practical to execute efficient trade.”