“`html

Scholars have disclosed numerical impacts of wolf hunts to furnish policymakers with fresh data as they deliberate measures to mitigate livestock losses

Wolf hunting has curbed livestock losses in a quantifiable manner, but it is certainly not a complete solution, as per a global research team led by the University of Michigan.

“Overall, hunting is not significantly alleviating the adverse effects associated with wolves. It does appear to affect livestock loss rates, but this influence lacks consistency, breadth, or strength,” stated Neil Carter, associate professor at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability and principal author of the latest study published in the journal Science Advances.

As government protections have facilitated the recovery of previously declining wolf populations, encounters between these predators and domesticated animals have become more frequent. While hunting is frequently proposed as a solution, it remains a highly contentious and divisive subject. Advocates on both sides are engaged in active litigation nationwide, aiming to modify or reinforce existing regulations.

However, several Northwestern states have already permitted hunting to some degree, which has afforded researchers the chance to introduce new insights into the discussion. The recent study, backed by the U.S. National Science Foundation, found that, on average, each wolf that was harvested by a hunter correlated with a 2% decrease in predation rates.

The research team also investigated how hunting impacted “lethal removals.” These are costly operations conducted by government bodies, targeting specific wolves after numerous or severe predation incidents, explained lead author Leandra Merz, assistant professor at San Diego State University.

According to the findings, hunting did not lead to any decrease in lethal removals.

“We’re not necessarily arguing against hunting—it’s important to clarify that—because there are other motivations for hunting,” remarked Merz, who was involved in the project during her postdoctoral fellowship at U-M’s School for Environment and Sustainability. “However, if the intention is to decrease livestock predation and we are relying on hunting to achieve that, its effectiveness falls short of our expectations.”

The research team also included collaborators from the University of Idaho, Washington State University, Ohio State University, and the GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences in Germany. The researchers emphasize that this study is a vital part of a small but expanding collection of research that adds valuable insights to the contentious debate surrounding wolf management strategies.

“There exists a significant amount of uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of public wolf hunting in addressing the negative impacts from these animals as their populations recover,” Carter noted. “In a topic that is divisive and controversial, minimizing that uncertainty should be a priority, as we may be making decisions that are neither as effective as they could be nor in the public’s best interests.”

And out come the wolves

“““html

The Endangered Species Act, often referred to as ESA, has safeguarded gray wolves throughout the contiguous United States for many years. In the 1990s, the U.S. initiated a successful campaign to reintroduce wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains. Within approximately two decades, the wolf population in this region expanded to the point that several states implemented legal hunting programs.

Since that time, wolf hunting has fluctuated due to legal actions initiated by various parties. Indeed, in 2020, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that gray wolf populations had significantly recovered, allowing for the removal of federal protections under the ESA, a ruling that was overturned by a court order in 2022. Moreover, the discussion is far from resolved.

“There are urgent matters concerning wolf management, both on a domestic and international scale,” Carter noted, referencing Michigan and Europe as areas where the issue is particularly prominent. “Stakeholders involved in wolf management are raising the topic of wolf hunting, and it’s a forthcoming conversation we will engage in.”

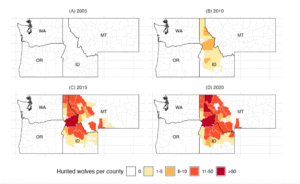

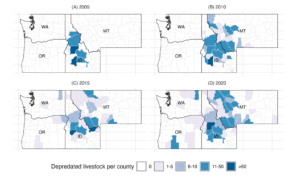

However, the actual effect of wolf hunting on safeguarding livestock remained unclear, indicating that many assumptions have permeated the discussion, Carter stated. Thus, he, Merz, and their team perceived an opportunity to illuminate this using data from regions where wolf hunting was permitted—Idaho and Montana—and from areas where it was not allowed, specifically Oregon and Washington.

The study examined data from those regions between 2005 and 2021, employing a variety of mathematical models to correlate hunting with its effect on livestock depredation and lethal removal events. No hunting was authorized before 2009, which aided researchers in establishing a control scenario.

Once again, hunting displayed no effect on the frequency of lethal removal operations, although predation had more complexity. On average, counties in the analysis lost approximately 3 to 4 livestock animals annually to wolves. With the previously mentioned 2% reduction, this equates to around 0.07 animals preserved for each wolf hunted, Carter remarked.

Nevertheless, the team highlighted that significant fluctuations exist from this average. For instance, Merz is aware of an Idaho rancher who lost 65 sheep in a single night to wolves. Moreover, losses do not need to be that extreme to result in severe economic impacts and profound psychological ramifications.

“The expenses can be quite substantial for an individual rancher, even over brief timeframes,” Merz stated. “We certainly do not wish to downplay that.”

From a policy standpoint, it is productive to consider what the most effective management strategies are to distribute these costs fairly and efficiently, Merz noted. The study indicates that hunting alleviates a minimal burden from ranchers, yet at no direct expense to them.

Then, there are non-lethal strategies that are demonstrating efficacy, Merz mentioned, including fladry, which combines flags and barriers that can be electrified. Even increasing human presence or human activities can help (drones playing AC/DC and dialogues from the film “Marriage Story” have recently garnered attention). However, the expenses associated with implementing and sustaining these measures are primarily borne by ranchers.

“There won’t be an easy resolution either way. If there were, we would have resolved it by now and would be utilizing it,” Merz remarked. “Nevertheless, the encouraging aspect is that people are incredibly innovative. We just need to be slightly more imaginative in how we share some of the costs and benefits. I believe beyond wildlife management, we often do that within society.”

“`