“`html

Nation & World

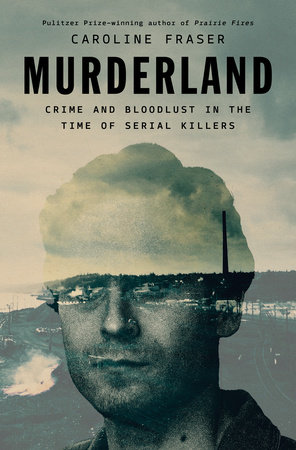

Why is the Pacific Northwest associated with numerous serial killers?

In ‘Murderland,’ the alum delves into the lead-crime theory through the prism of her childhood memories in the region.

In Caroline Fraser’s 2025 publication “Murderland,” the atmosphere is perpetually dense with pollution, and nefarious entities lurk at every turn.

Fraser, Ph.D. ’87, in her first volume following “Prairie Fires,” her biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, investigates the surge of serial killers in the 1970s — interweaving ecological and social history, memoir, and unsettling depictions of violence and predation. The narrative shifts the traditional emphasis on the psychology of serial killers to their surrounding environment. As the Pacific Northwest grapples with a string of serial homicides, Fraser directs her attention to the nearby smelters expelling clouds of lead, arsenic, and cadmium while industries, government officials, and even the public conveniently ignore the pollution.

Fraser links many of the Pacific Northwest’s most infamous killers to these industrial emissions. Ted Bundy, whose actions and background are examined more than any other figure, was raised in the shadows of the ASARCO copper smelter in Tacoma, Washington. Gary Ridgway also spent his youth in Tacoma, while Charles Manson was incarcerated for a decade at a prison nearby, where lead contaminated the ground. Richard Ramirez, dubbed the Night Stalker, grew up beside a different ASARCO smokestack in El Paso, Texas, long before he committed his offenses in Los Angeles.

Fraser’s personal encounters growing up in Mercer Island, Washington, introduce another unsettling layer. A classmate’s father explodes his home with the family inside, while another classmate becomes a serial predator. Her Christian Scientist father is threatening and abusive, compelling Fraser, as a child, to contemplate ways to eliminate him, possibly by pushing him off a boat. The malevolence is relentless; something is undeniably amiss.

Fraser allows readers to decide how significantly environmental degradation contributed to the murders outlined in her work. “Numerous factors probably drive someone to commit these kinds of offenses,” she stated in an interview. “I did not frame it as a study in criminology or a scholarly work on the lead-crime hypothesis. I simply aimed to narrate a history of the region — what I recall of it — and craft a narrative that encompassed all these elements.”

“I did not frame it as a study in criminology or a scholarly work on the lead-crime hypothesis. I simply aimed to narrate a history of the region — what I recall of it — and craft a narrative that encompassed all these elements.”

Fraser has contemplated these concepts for years. Prior to the publication of “Prairie Fires,” she had already penned some of the memoir segments of the book, recalling the offenses and peculiar incidents near her family’s residence. She was long curious about why so many serial predators emerged from the Pacific Northwest and whether it was mere coincidence.

While she was aware of the pollution in Tacoma during her childhood — the area’s scent was dubbed the “Aroma of Tacoma” due to sulfur emissions from a local factory — it was only years later that she comprehended the full extent of industrial production and environmental harm.

Some realizations emerged fortuitously. While examining one property on Vashon Island, situated across the Puget Sound from West Seattle, she encountered a listing with the foreboding alert — “arsenic remediation needed.”

“That truly caught my attention,” she remarked. “How can arsenic be present on Vashon Island?” Further investigation revealed that the arsenic originated from the ASARCO smelter at the southern tip of the same waterway. The fallout extended much further; the Washington State Department of Ecology reports that air pollutants — predominantly arsenic and lead — from the smelter settled on the surface soil of over 1,000 square miles of the Puget Sound Basin.

“Much of Tacoma, with a populace nearing 150,000, will register elevated lead levels in local soils,” Fraser expressed in the book, “but the Bundy family resides close to a series of astonishingly high measurements of 280, 340, and 620 parts per million.”

This connection shifted Fraser’s focus toward the physical surroundings of these serial killers and away from other aspects — such as abusive backgrounds — which true-crime authors have typically emphasized more heavily.

In this ecological exploration, Fraser directs readers to once-widespread sources of pollution like leaded gasoline and the industrial forces that championed them in defiance of public health advisories.

American doctors raise alarms about lead particles potentially blanketing the nation’s roads and highways, insidiously poisoning neighborhoods over time. They label it “the greatest single question in the field of public health that has ever confronted the American populace.” Unfortunately, their concerns are dismissed, while Frank Howard, a vice president of the Ethyl Corporation, a collaboration between General Motors and Standard Oil, refers to leaded gasoline as a “divine gift.”

Although Fraser does not explicitly endorse the lead-crime theory, the essence of the premise — that increased lead exposure results in elevated crime rates — remains pivotal. In the concluding chapter of the book, Fraser references the work of economist Jessica Wolpaw Reyes, Ph.D. ’02, who determined in her dissertation that lead exposure correlates with higher adult crime statistics.

No matter how conclusively this hypothesis can be validated, Fraser posits that the links between unabashed and unchecked pollution and violent crime merit examination. In “Murderland,” she presents this idea, alongside an era of crime, through a fluid, haunting narrative.

“`