“`html

Communities backing America’s livestock sector experience poorer air quality and have more at-risk populations compared to comparable communities lacking feedlots

The United States hosts over 15,000 cattle and hog feeding operations. These facilities raise 70% of the nation’s cattle and 98% of its hog population.

For the first time in U.S. history, we can now confidently pinpoint the majority of these locations, thanks to research conducted by the University of Michigan.

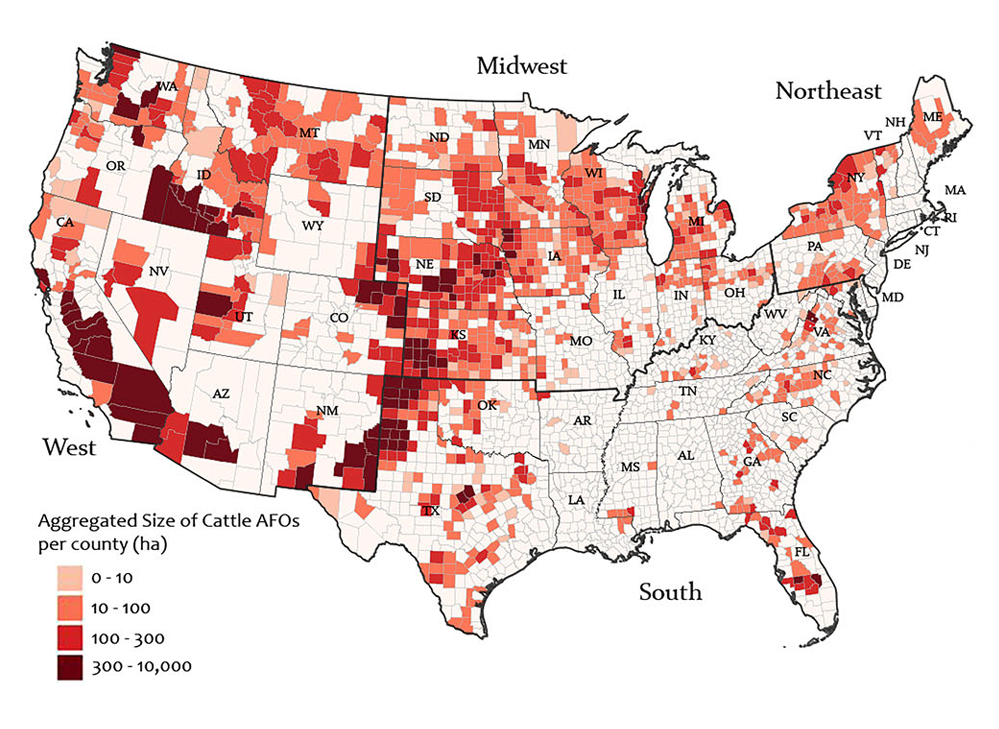

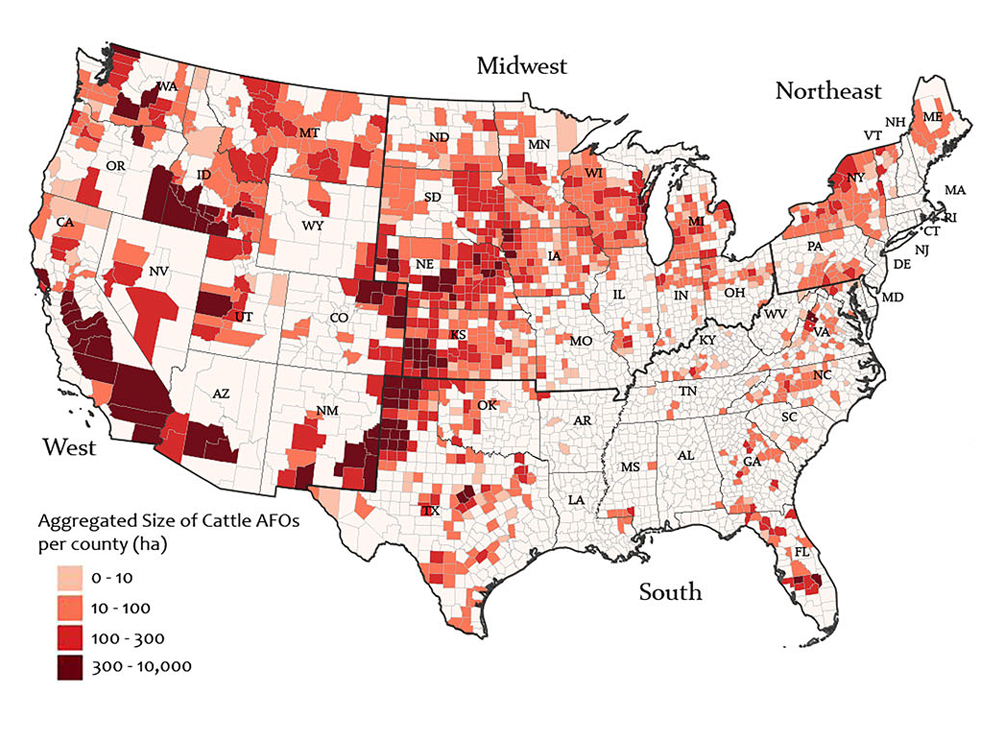

The research group discovered that a quarter of all hog and cattle feeding facilities are positioned within just 30 counties out of more than 3,000 nationwide. Additionally, they identified that an air contaminant linked to cardiac and respiratory problems near these animal feeding operations, or AFOs, was more prevalent compared to similar counties lacking such operations.

The researchers also found a greater probability of encountering vulnerable and marginalized neighborhoods near AFOs. Notably, these communities typically experience lower levels of health insurance coverage and education and have higher percentages of Latino residents.

“One of the revelations from this study is that we can concentrate on a select few counties to significantly address health repercussions within these communities,” stated Joshua Newell, a senior contributor to the report published in Communications Earth & Environment.

“For policymakers, government entities, or community groups concerned about these matters, this enables them to formulate highly focused policies or initiatives,” remarked Newell, a professor at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, or SEAS. “That’s why creating this spatial map is crucial.”

‘This doesn’t add up’

The term AFO designates a particular kind of operation where animals are housed and fed for over 45 days in a year, explained lead author Sanaz Chamanara. Animal waste is also stored onsite, which significantly affects air quality. Beyond its odor, it contributes to dust and particulate matter that contaminate the atmosphere.

While agencies such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Agriculture gather some data on AFOs, there exists variability and inconsistency in data reporting nationwide. Consequently, the existing data was fragmented and limited in both scope and precision, Chamanara noted.

For instance, Chamanara synthesized government records to initiate with an initial list of over 10,000 AFO locations. However, upon validating these sites with satellite images, she discovered thousands of locations without active AFOs.

“I can’t recall the exact figures, but, in the end, the data retained around 5,000 locations,” Chamanara noted, a quantity that was alarmingly low. “I observed that and thought, ‘This doesn’t add up.’ That was when I began the comprehensive development of the dataset.”

A community science initiative known as Counterglow provided vital insights on where to begin searching for the overlooked AFOs, but Chamanara had to sift through satellite images of every county in the continental U.S. to identify the operations. This meticulous endeavor was a crucial part of her doctoral research for SEAS and this new analysis. Nonetheless, Chamanara is most enthusiastic about the future opportunities this will create.

“The primary aim of…

“““html

“This undertaking was to create this dataset to ensure that other scholars can access it,” stated Chamanara, who currently is employed by Microsoft. “It can benefit public health authorities and researchers focused on environmental justice.”

Alongside pinpointing sites, Chamanara also charted the scope of each hog and cattle feeding operation. From that evaluation, the nation’s AFOs encompass an area equivalent to approximately 500,000 football fields, with cattle operations making up nearly 80% of that figure. For context, there are roughly 16,000 high school football fields across the country, according to the National Football Foundation.

The group’s dataset is accessible online as additional material to their research.

“We reside in one of the most data-abundant nations globally, yet until Sanaz Chamanara undertook this project, we lacked a thorough dataset of these extensive operations,” remarked Dimitris Gounaridis, an assistant research scientist at SEAS and a co-author of the publication.

“And while we’re not asserting that this covers every AFO in the U.S., it’s a sufficiently large sample to draw conclusions confidently.”

‘It’s harmful material’

Given that nationwide data exists on air quality and the socioeconomic structure of communities, the U-M team was able to employ its new data to systematically explore correlations with the presence of AFOs on an unparalleled scale. Past research has explored these associations, but earlier studies were limited to much smaller, local areas.

In the U-M investigation, the group focused on air pollution referred to as PM2.5 as a case study. PM2.5 represents particulate matter that is 2.5 micrometers or smaller. That’s roughly a millionth of an inch, meaning these particles can be easily inhaled by individuals exposed to them. This pollution is associated with various health effects concerning the heart, lungs, and airways.

“It persists in the atmosphere and can penetrate deeply into your lungs, leading to scar tissue. It’s harmful material. There are essentially no safe levels of exposure,” stated Benjamin Goldstein, an assistant professor at SEAS and a senior author of the new research.

The group discovered that the PM2.5 levels were, on average, 28% greater near cattle feeding operations and 11% higher near hog operations when compared with similar counties devoid of AFOs.

The researchers utilized census data to evaluate the sociodemographic composition of communities located near feeding operations. While the team’s research does not clarify if an AFO is established in a specific community or if a certain community develops around an AFO, this does not lessen the core message of the study.

“The meat you consume originates from somewhere. It requires substantial space and generates considerable pollution,” Goldstein explained. “And someone else and another location must endure that pollution.”

“`