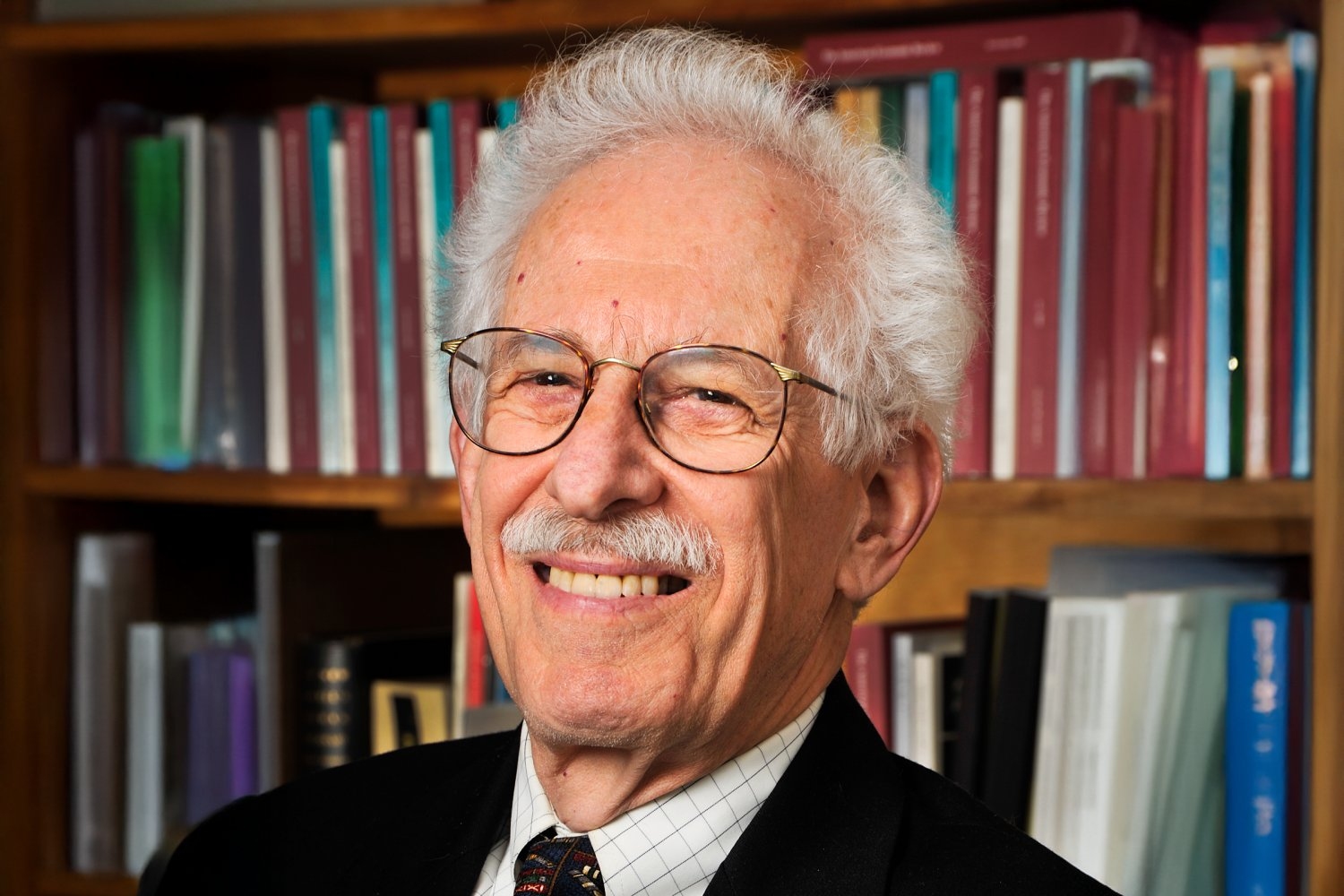

Peter Temin PhD ’64, the MIT Elisha Gray II Professor of Economics, emeritus, passed away on Aug. 4. He was 87.

Temin was an eminent economic historian whose research encompassed an impressive array of subjects, ranging from the British Industrial Revolution and Roman economic history to the reasons behind the Great Depression and, later in his career, the deterioration of the American middle class. He also made significant contributions to the modernization of economic history through his methodical application of economic theory and data assessment.

“Peter was a passionate educator and an exceptional colleague, who could animate economic history like few others,” states Jonathan Gruber, Ford Professor and chair of the Department of Economics. “As an undergraduate at MIT, I recognized Peter as a captivating instructor and UROP [Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program] mentor. Later, as a faculty member, I appreciated him as a reliable and encouraging colleague. He was an excellent person to discuss everything with, from research to politics to life at the Cape. Peter embodied the complete package: an outstanding scholar, an exceptional teacher, and a committed advocate for public goods.”

When Temin commenced his career, the discipline of economic history was experiencing a transformation within the profession. Guided by luminaries like Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow, economics had evolved into a more quantitative, mathematically rigorous field, and economic historians adapted by adopting the new instruments of economic theory and data collection. This “new economic history” (now also referred to as “cliometrics”) revolutionized the area by integrating statistical analysis and mathematical modeling into the examination of historical events. Temin was a trailblazer of this novel methodology, employing econometrics to reevaluate significant historical occurrences and showcasing how data analysis could challenge long-standing beliefs.

A prolific academic who penned 17 books and edited six, Temin made vital contributions to an immensely varied range of topics. “Kind and brilliant, Peter was a distinctive kind of scholar,” comments Harvard University Professor Claudia Goldin, a fellow economic historian and recipient of the 2023 Nobel Prize in economic sciences. “He was a macroeconomist and an economic historian who later addressed contemporary social issues. In between, he studied antitrust, health care, and the Roman economy.”

Temin’s initial work centered on American industrial progress during the 19th century and refined the hallmark approach that swiftly established him as a leading economic historian — merging robust economic theory with a profound comprehension of historical context to reassess the past. Temin was recognized for his extensive examination of the Great Depression, which frequently contradicted prevailing views. By asserting that elements beyond monetary policy — including the gold standard and a drop in consumer spending — were pivotal aspects of the crisis, Temin helped reshape the perspective economists hold regarding the disaster and the role of monetary policy in downturns.

As his career advanced, Temin’s endeavors increasingly broadened to encompass the economic history of additional regions and eras. His subsequent work on the Great Depression placed more emphasis on the international dimensions of the crisis, and he made substantial contributions to our grasp of the forces driving the British Industrial Revolution and the characteristics of the Roman economy.

“Peter Temin was a titan in the realm of economic history, with work influencing every dimension of the field and innovative ideas supported by meticulous research,” remarks Daron Acemoglu, Institute Professor and recipient of the 2024 Nobel Prize in economics. “He contested the contemporary interpretation of the Industrial Revolution that highlighted technological advancements in a few industries, instead pointing to a broader transformation within the British economy. He engaged with the eminent historian of antiquity, Moses Finley, contending that markets within the Roman economy — particularly land markets — functioned effectively despite slavery. Peter’s impact and contributions will be enduring.”

Temin was born in Philadelphia in 1937. His parents were activists who instilled a sense of social responsibility, and his elder brother, Howard, became a geneticist and virologist who was awarded the 1975 Nobel Prize in medicine. Temin obtained his BA from Swarthmore College in 1959 and subsequently earned his PhD in Economics from MIT in 1964. From 1962 to 1965, he was a junior fellow with Harvard University’s Society of Fellows.

Temin began his career as an assistant professor of industrial history at the MIT Sloan School of Management before joining the Department of Economics in 1967. He served as department chair from 1990 to 1993 and held the Elisha Gray II professorship from 1993 to 2009. Temin received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2001, and held the presidency of the Economic History Association (1995-96) and the Eastern Economic Association (2001-02).

At MIT, Temin’s academic accomplishments were complemented by a strong dedication to engaging with students as an educator and mentor. “As a researcher, Peter could pinpoint the essential questions regarding a topic and find answers where others were struggling,” says Christina Romer, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Obama and a former student and mentee. “As a teacher, he could transform inattentive students into an energetic discussion that led us to believe we had independently grasped the material, even though he was skillfully guiding us all along. And as a mentor, he was consistently supportive and generous with both his time and extensive knowledge of economic history. I feel fortunate to have been one of his protégés.”

Upon becoming the economics department head in 1990, Temin focused on hiring recent PhDs and other junior faculty. This foresight continues to yield benefits — among his junior hires were Daron Acemoglu and Abhijit Banerjee, and he initiated the recruitment of Bengt Holmström for a senior faculty post. All three went on to receive Nobel Prizes and have been foundational figures in economics research and education at MIT.

Temin remained an engaged researcher and author following his retirement in 2009. Much of his later work shifted toward the contemporary American economy and its profound divisions. In his influential 2017 book, “The Vanishing Middle Class: Prejudice and Power in a Dual Economy,” he contended that the United States had evolved into a “dual economy,” with a flourishing finance, technology, and electronics sector on one hand and, on the opposite side, a low-wage sector marked by stagnant prospects.

“There are reflections of Temin’s later writings in present department initiatives, such as the Stone Center on Inequality and Shaping the Future of Work,” notes Gruber. “Temin was, in many respects, ahead of his time in addressing inequality as an issue of central significance to our discipline.”

In “The Vanishing Middle Class,” Temin also examined the impact of historical events, especially the legacy of slavery and its consequences, in shaping and sustaining economic disparities. He further delved into these ideas in his final book, “Never Together: The Economic History of a Segregated America,” published in 2022. While Temin may be best known for his work applying modern economic methodologies to history, this later work illustrated that he was equally skilled at the reverse: utilizing historical analysis to illuminate contemporary economic challenges.

Temin actively participated in MIT Hillel throughout his career, and outside the Institute, he enjoyed staying active. He was often seen walking or biking to MIT, and taking strolls around Jamaica Pond was a cherished activity in his final months. Peter and his late wife Charlotte were also enthusiastic travelers and art collectors. He was a loving husband, father, and grandfather, who was profoundly devoted to his family.

Temin is warmly remembered by his daughter Elizabeth “Liz” Temin and three grandsons, Colin and Zachary Gibbons and Elijah Mendez. He was preceded in demise by his wife, Charlotte Temin, a psychologist and educator, and his daughter, Melanie Temin Mendez.